Veteran radio broadcaster Leonard Mambo Mbotela (left) and Christopher Kirwa of Coke during a past football match at Nyayo National Stadium, Nairobi. PHOTO | NATION MEDIA GROUP

My great-grandfather, Mbotela Senior, hailed from the Yao clan in Central Malawi. He was born in a year believed to be 1865.

Their language was known as Chiyao. The Yao are predominantly fishermen. A substantial number of Yao are also found in Mozambique and a few in southern Tanzania.

Around 1878, Mbotela Sr was captured in his home village by slave traders and put on a ship en route to Europe. However, the British – through a man called Bartle Frere – had negotiated a treaty with the Sultan of Zanzibar to end slave trade.

Thus, the ship with human cargo was intercepted in Zanzibar by the anti-slavery team and re-routed to Freretown in Mombasa where the would-be slaves were freed and given a place to live. Mbotela gladly accepted to settle in Mombasa. I’m sure he did not have an idea of how to travel back to Malawi. Furthermore, having been forcefully separated from his family – and traumatised in the process – it was better to be a free man in a foreign land than a slave in Europe.

Owing to the hardships of those days, it was not advisable to embark on risky voyage back home. He remained in Mombasa.

While in Freretown, he was offered religious training, formal education, among other things. He became a Christian and lived in Mombasa, unaware of what had become of his parents and other relatives in Malawi.

Freretown, which was a major market for slaves, was named after Bartle Frere because of his efforts in campaigning against, and even stopping, the trade in East Africa.

Whenever slaves from Kenya and parts of Tanzania were brought to this notorious market for sale, a huge bell was rang for the buyers to “select the goods”.

In this unpleasant and callous business, human beings were sold like vegetables. The stronger and healthier a slave was, the higher the price they fetched. Weak ones were either neglected or bought cheaply.

Occasionally, they were offered free of charge as an “after-sales service” to a trader who had bought the most “goods”.’ This demeaning trade annoyed Frere who spoke against it and pushed for its abolition

Eventually, when the trade was abolished, the majority of the rescued slaves were allowed to call this place home.

Even those from other regions like Bombay, Malawi, Zanzibar, Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), Northern Rhodesia (Zambia) were settled here.

Most of these rescued slaves from other countries were assimilated in the Kenyan coast and became part of the Swahili and Arab people.

That is how Mbotela Sr found himself in Freretown. A school and a church were later established in Freretown. Evangelism and education began in Freretown before moving deep into the interior.

The huge bell that was rang in Freretown (as far back as 1800) for merchants to pick slaves is still there. The area has been renamed Kengeleni – a Kiswahili word for bell.

Historians say that between 1600 and 1900, close to 15 million Africans were captured and transported to America and Europe as slaves.

As they waited to be sold and transported, the slaves were chained in underground dungeons that were hardly five feet tall. For many days or even months, the slaves lived in these dungeons that had no ventilation awaiting buyers.

They were fed once a day. The dungeons also served as toilets.

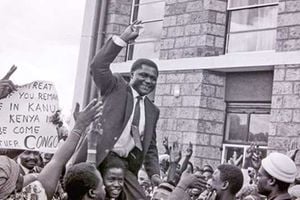

Leonard Mambo Mbotela (right) when he paid a courtesy call on President Daniel arap Moi at his Kabarak, Nakuru home on August 31, 2008.

**

So, my great grandfather, Mbotela Sr, was rescued from slavery and became a member of Freretown society.

The missionaries who formed Freretown made it an autonomous village full of Europeans. It had its own rules and was set apart from the rest of society. It was “a town of peace in the city of war”.

The majority of the inhabitants were former slaves. Freretown market facilitated the sale of produce and goods obtained from the surrounding areas.

The traders paid tax to the missionary board, which prescribed market regulations and tax rates.

Freretown developed its workshop that produced items like bricks, mats, tiles and other construction materials.

A major hospital was built there in 1885. The community also maintained its boat, which sailed monthly between Freretown and Unguja (in Zanzibar).

Freretown was governed by laws formulated in 1888. Those laws regulated social activities and movement. The missionaries imposed a 9pm to 6am curfew and limited the flow of visitors into the area.

Offenders were punished and jailed. The community had its own jail. Every inhabitant was expected to convert to Christianity.

This community had several churches and schools, which were headed by Reverend William Price.

The performance of traditional songs in Freretown was forbidden by the missionaries. Africans were arranged into bands and choirs that mainly sang religious songs.

The Freretown people were completely under the influence of the White man’s culture and all of them became Christians and very much attuned to Western civilization.

Virtually everyone in this community, young and old, was taught how to read and write.

While in Freretown, Mbotela Sr got basic formal education. He teamed up with some Yao former slaves from his native Malawi and interacted freely with people from other backgrounds.

Because of his ability to read and write, he was recruited to work for the missionaries. His duties were varied, ranging from domestic house chores, messenger assignments to clerical work.

He was a trustworthy, outgoing, likeable person; a trait that I can attest runs in most of his descendants.

Out of this, he developed a good relationship with the missionaries and other Europeans in Freretown. Eventually, he was identified and recruited as a porter to accompany the Whites who were by that time moving a lot, either as businessmen under the Imperial British East Africa Company, missionaries or even explorers.

His first major assignment as a porter was in early 1885 when he was picked by the Church Missionary Society (CMS) office in Mombasa to accompany the party of Bishop James Hannington on a long trip to Uganda, on foot from Mombasa, about 1,200 kilometres away.

Their caravan passed through thickets, mountains, forests, flooded rivers, wetlands and plain lands. There were no roads and travelling was rigorous and risky.

**

From Mombasa, the entourage went through the jungle of Taita (now Tsavo National Park), Ukambani, Maasailand, Kericho and down to Kakamega.

Months later, they arrived in present Western Kenya and made a stopover at the home of King Nabongo Mumia of Wanga (now Mumias).

They encamped there for several days before proceeding to Uganda.

When they arrived in Uganda at a place called Busoga, the trip took a tragic turn. Bishop Hannington was attacked and killed by soldiers of the then King of Buganda, Kabaka Mwanga, who loathed Christianity, which was slowly creeping into his territory and the larger Uganda.

Most of the Africans who accompanied this famous clergyman as porters, cooks and security men, were not spared either.

Hannington’s team comprised more than 50 people but fewer than 10 survived.

Mbotela Sr, miraculously, was one of the few who escaped the attack by Kabaka’s army.

He and other escapees found their way back to Mumias and reported the matter to Nabongo who was friendly to the Europeans. Several of them settled in Mumias.

Hannington’s murder frightened Mbotela Sr and his fellow survivors. They recounted the tragic story to the Nabongo and other Europeans in Mumias.

It is said that Bishop Hannington told his murderers before he died: “Go, tell your King (Mwanga) that I have purchased the road to Uganda with my blood.”

From Mumias, Mbotela Sr teamed up with other porters and walked back to Mombasa; a journey that took four to six months.

They kept stopping and changing direction, especially whenever they encountered hostile tribes.

Despite the risks, Mbotela Sr and the other surviving porters arrived safely in Mombasa.

They gave a first-hand account of the murder of Bishop Hannington to the church in Mombasa, where Hannington had served before embarking on the fateful journey.

The other missionaries were devastated by the news.

Bishop Hannington’s murder became one of the saddest stories among the CMS adherents.

After safely returning to Freretown, Mbotela Senior continued with his usual duties of serving the missionaries.

In 1887, he married to Halima, a girl who had been rescued from slavery in Zanzibar and taken to Freretown. Her other name was Ida. No one knew her parents and siblings.

This marriage, I was told, was organised by the missionaries who preferred to see Christians marry fellow Christians.

**

In 1888, the young Christian couple – Mbotela and Ida – was blessed with a son whom they named Juma Mbotela. Years later, Juma became father of James. And James became my father.

From the story of my great grandfather, Mbotela Sr, I can trace my roots back to Malawi, in the Yao community. However, I cannot claim to be a Yao because I was never born or brought up among them. I don’t know any relative there; and have never lived with them. But that’s where my origin can be traced to.

None of my relatives ever attempted to trace our origins in Malawi. Perhaps one day my children (or grandchildren) will make attempts to find the family that our great grandfather left in Malawi in 1865.

I am sure where Mbotela Sr came from, he must have left behind brothers, sisters and other relatives who have now multiplied. It would be nice to know them.

I was born and brought up in Mombasa. Many people often ask about my tribe and I tell them that I’m a Kenyan who has no attachment to any of the 43 Kenyan ethnic communities.

However, by the virtue of coming from Mombasa, many people often conclude that I must be a Swahili. Often times, I have had to accept that I’m a Swahili because I was born and raised among them.

**

I was born at Lady Grigg Hospital in Mombasa on May 29, 1940 as the firstborn of James and Ida.

My father was teaching at Shimo La Tewa High School.

I was named Leonard after the famous British missionary, Bishop Leonard Beecher. This missionary taught my father at Alliance High school in 1926.

My parents told me that I was also named ‘Mambo’ because I was very talkative right from childhood.

I liked telling people stories, recounting what I had witnessed earlier in the day, commenting on issues and cracking jokes.

My mouth hardly shut, they said. I was a cheeky boy who liked teasing people.

I was commonly referred to as “mtoto wa mambo mengi.” (a talkative child) or “mtoto mcheshi” (a naughty boy).