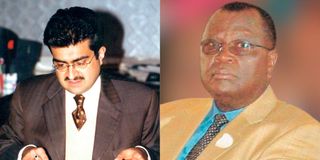

Kamlesh Pattni and James Kanyotu, former spymaster. As a director and shareholder of Goldenberg International, Kanyotu was the engine behind Pattni’s audacious schemes.

In case you missed it, begin the Pattni series with Chapter 1: Inside Pattni’s wild world of sleaze

-----

Eighty-three days after the registration of Goldenberg International, Kamlesh Pattni, the architect of Kenya’s most infamous financial scandal, arrived at the Treasury building in an unmarked vehicle. Beside him sat James Kanyotu, the shadowy and feared spymaster who had, for years, wielded the kind of power that made men shudder in his presence.

Together, they descended into the dimly lit basement and parked at the VIP section. Their destination: the 14th-floor office of Professor George Saitoti, Vice President and Minister for Finance.

This meeting was not mere protocol — it was a gambit in a high-stakes game of deception and greed. For the Goldenberg International scheme to flourish, every piece on the chessboard needed precise alignment.

Prof Saitoti, a man whose demeanor betrayed his fragility, was their mark. Timid and perpetually anxious, he lived in the shadows of his own unease, navigating the treacherous waters of corruption like a man walking on thin ice.

Former Vice President George Saitoti.

In the corridors of power, Saitoti was no predator but prey, easy to corner, easier still to manipulate. A few months back, he had been poisoned but had survived. Now, a deadly proposal was shoved to his desk by a man who commanded Kenya’s intelligence.

Kanyotu: Engine behind Pattni's schemes

The late James Kanyotu.

Kanyotu needed no introduction. In the world of shadows where he thrived, his reputation was mythic. As the head of the feared Special Branch—notorious for its brutal efficiency—his reputation preceded him. Operating with the ruthless precision of Germany’s Stasi, the Special Branch silenced dissent with chilling finality in the network of torture chambers, secret safe houses, and forest hideouts.

Intimidation was a tool of terror and business. In the streets of Nairobi, Kanyotu’s name alone paralysed the staunchest critics. Journalists never dared to take his photos or write about him.

As a director and shareholder of Goldenberg International, Kanyotu was the engine behind Pattni’s audacious schemes. His influence opened doors that would otherwise remain sealed, granting Pattni the unfettered power he needed to navigate the murky depths of Kenya’s kleptocracy. In this Treasury meeting, a new chapter of plunder was about to be scripted. Prof Saitoti was being set as a support cast.

According to Pattni, it was Kanyotu who orchestrated his audience with President Moi at the secluded Kabarnet Gardens residence. There, Pattni claimed to have laid out his audacious proposal. As the story goes, he didn’t come empty-handed; he arrived with a suitcase with Sh5 million — a gift, or so it was presented.

For Moi, who had cultivated a reputation for accepting “donations” with both hands, such transactions were routine, cloaked under the veneer of goodwill and political patronage. Yet, when the Judicial Commission later dissected the Goldenberg scandal, they dismissed Pattni’s tale as “clearly incredible,” and as yet another layer of fiction in the Goldenberg saga of deceit. Patni was a master of imaginations – and every word he spoke was peppered with slices of lies.

Prof Saitoti, perhaps frightened by Kanyotu’s presence, approved Pattni’s proposal without asking questions. He later maintained in his defence that his eventual approval of was anchored on existing government policy. What he did not say was that this policy had its roots in the clandestine desire to loot the Treasury.

Kanyotu, as head of the Special Branch, stood at the nexus of this covert activity. Armed with unparalleled intelligence on mineral exports, he was not merely an observer but an enabler in a web of opportunism. As Justice Bosire’s Commission later remarked, “Goldenberg’s application… appears to us to have been opportunistic,” a masterstroke of exploitation disguised as economic innovation.

Glittering vision of untapped wealth

In the carefully worded letter that Pattni handed to Professor Saitoti, he painted a glittering vision of untapped wealth saying that “Kenya has a reasonable supply of diamonds and gold.”

It was a lie.

He also wrote confidently that his “company has the capacity to buy diamonds, which are in large supply here in Kenya, and we have a ready and unlimited export market.” It was a masterstroke of fabrication—convincing on paper but hollow in truth. Kenya had no diamonds, at least not legally. Any talk of such riches was in the mindset of a smuggler, and Prof Saitoti, seasoned in the art of governance, knew this all too well.

Yet Pattni’s genius lay not in the truth but in exploiting its absence. He had identified a lucrative loophole in Kenya’s proposed export framework. Compensation for diamond, gold, and other precious stones was hinged solely on their physical examination and certification before export — a process that was, in essence, a game of paperwork. Once certified, foreign currency was to be deposited with an authorised dealer, typically a bank, within 90 days of payment.

However, the rules governing this delicate dance were not immutable. With the repeal of the Exchange Control Act through the Finance Act of 1993, effective September 1 of that year, the financial floodgates were thrown open. Foreign currency earned from services, such as tourism, no longer qualified for export compensation. This change tightened some doors while leaving others wide open, perfect for those like Pattni who thrived in the margins of law and ethics.

Pattni’s scheme wasn’t just audacious; it was brilliantly opportunistic. Where others saw regulations, he saw a lattice of vulnerabilities ripe for exploitation — a glittering mirage that promised wealth but left behind a trail of deception and scandal.

In this theater of greed and guile, where narratives clashed and truths dissolved, the players each wore masks — of patriotism, policy, and power—while the country watched, oblivious to the grand larceny unfolding behind the curtain.

Looting Treasury

Chief architect of the Goldenberg scandal, Mr Kamlesh Pattni, and Mr Charles Mbindyo wait to be released from the police cells at the High Court, Nairobi, in May 1995.

Before Goldenberg International emerged, there was Aurum Limited, an earlier contender seeking monopoly rights to export gold. However, Goldenberg outmaneuvered its predecessor with astonishing ease, courtesy of high-level political patronage.

In a dramatic departure from due process, the company secured not only exclusive export rights but also an unparalleled 35 percent export compensation—far exceeding the promises made by Finance Minister Prof George Saitoti during his June 7, 1990, budget speech.

Ordinarily, such a proposal would undergo rigorous technical evaluation and the preparation of a sessional paper for Cabinet deliberation. Yet, in this case, protocol was flagrantly disregarded. Charles Mbindyo, then Permanent Secretary at the Treasury, later testified that none of these procedural safeguards were followed.

Instead, Goldenberg International’s licensing was expedited through irregular means, with the company ushered into operations without the scrutiny typically required for ventures of such magnitude. Pattni promised Treasury that he would bring $50 million per year.

Pattni had another proposal: that due to the numerous transactions on a daily basis and to a tune of Sh200 million every month, that he be allowed to set up a finance company, Goldenberg Finance Limited. He claimed that this would reduce security risks during cash transit. Pattni was granted his wish. What followed was a whirlwind of clandestine deals and questionable authorisations, the ripple effects of which would engulf the nation’s economy in scandal.

After Saitoti’s approval of a 35 percent export compensation, the Department of Customs found it difficult to accommodate the extra 15 per cent since it was not anchored on any law.

But before parliament was asked to approve, Treasury PS Charles Mbindyo in January 1991 wrote a letter to Prof Saitoti requesting permission to pay them [meaning Kanyotu and Pattni] the 15 per cent ex gratia payment “each time they produce evidence of exportation of [diamond and gold].” Prof Saitoti agreed.

Voices of dissent at Treasury ignored

The National Treasury Building in Nairobi.

To have the extra 15 per cent to pay Pattni, a decision was made at the Treasury to get Parliament approve the extra expenditure. This was done in the 1991/92 and 1992/93 financial year – pushed through by Prof Saitoti to accommodate Pattni’s greed.

At the Treasury, voices of dissent that emerged were ignored. For instance, when Prof Terry Ryan wrote a letter to Prof Saitoti saying “it would be good for us to try and sort out the gold question” he was ignored.

Prof Ryan, a longtime advisor at the Treasury, had even shown that the previous Arum Limited request was guaranteeing $40 million a year and proposing to export more than Goldenberg without a monopoly. Prof Ryan described the monopoly as “illegal” and felt that the export compensation “infringes nit just the spirit but also the letter of the Export Compensation Act.”

Treasury then started to mislead Parliament and while Charles Mbindyo’s junior, Njeru Kirira and Prof Ryan voiced concern on the legality of Goldenberg’s compensation, nobody dared to confront Prof Saitoti.

Despite their misgivings, it was the duty of the Treasury to make sure that an export had taken place of the eligible goods before forwarding the payment claim to Commissioner of Customs.

Goldenberg had initially sought monopoly power under the pretext of eliminating smugglers, yet Pattni, its architect, became ensnared in the very web he claimed to oppose. In a dramatic twist, Pattni was caught smuggling gold from Bunia, Zaire, with his plane impounded at Nairobi’s Wilson Airport after landing after hours. Despite Kenya lacking any significant gold discoveries, the country’s Economic Survey reports began to reveal astonishingly inflated figures, later deemed by economists as "abnormal" and "outside the normal trend."

The figures spoke volumes. In 1991, the value of exports stood at a modest Sh1.5 billion but skyrocketed to Sh9.6 billion within months, as reflected in customs trade reports. These startling numbers were quickly dismissed as fraudulent, a clear indication that Pattni and his cabal had doctored them to suit their agenda.

The monopoly granted to Goldenberg under the Diamond Industry Protection Act positioned it as the sole licensed entity in Kenya. Yet, a closer examination exposed a house of cards. Alleged transactions with Servino Securities, a Swiss-based "importer," unraveled as fiction. The supposed importer’s address led investigators to a printing firm, with no trace of Servino on Swiss company registers. Pattni, it turned out, had concocted a façade—a company registered in Panama masquerading as a Swiss buyer.

More so, neither Treasury nor Central Bank could validate the meteoric rise in gold and diamond exports. Pattni’s purported consignees — Ketan Somaia’s DPN Trading and World Duty Free in Dubai — were equally dubious. Somaia outright denied dealing in minerals, asserting his business revolved around industrial hardware. Meanwhile, documents tied to World Duty Free were flagged as forgeries.

Local banks raised alarms about irregularities in currency declaration forms. When confronted, Pattni excused the discrepancies with vague explanations, claiming:

"We are trying to learn and systematise ourselves...The invoices are being raised in Kenya shillings instead of convertible currencies because, at the time of our meeting in Geneva, we were arguing about which exchange rate to use."

Established another firm - Exchange Bank

The truth was far more sinister. Pattni sought to exploit the system by depositing foreign currency in local banks under the guise of export proceeds. This illusion allowed him to claim lucrative export compensation payouts. The scheme was remarkably straightforward: foreign currency would be sent abroad, only to be remitted back to Kenya to simulate export earnings and qualify for compensation.

Pattni's machinations reached new heights with the establishment of Exchange Bank, which became a hub for buying foreign currency on the black market. Funds were funneled into an account in London under the pseudonym "Ratan," which Pattni controlled. This shadowy operation expanded as Goldenberg opened multiple bank accounts to launder vast sums of foreign exchange.

To secure export compensation, a high-level meeting was convened on November 1, 1990, attended by Prof. George Saitoti, Mbindyo, and Central Bank Governor Eric Kotut. Skeptics of the scheme were sidelined, with a trusted insider, David Waiganjo, tasked with managing Goldenberg’s financial returns. Armed with a license to handle foreign currency—originally meant for hotels—Goldenberg blurred the lines between legitimate proceeds and fabricated ones. The result? Every dollar of foreign currency it possessed became a claimable asset for compensation.

And thus, a monumental racket was born. It thrived on deception, leveraging state institutions, and exploiting loopholes to siphon billions from Kenya’s coffers under the veneer of economic patriotism.

@johnkamau@ [email protected]