MI5 intelligence officer Walter Bell (right) and his wife Tattie.

| File | Nation Media GroupNews

Premium

When the British planted mole in Kenyatta’s circles

A new book has revealed the secrets of an MI5 officer assigned to founding President Jomo Kenyatta to win his trust and develop a working relationship with the British on security and intelligence issues.

The book, “A Faithful Spy”, details how MI5 chief Roger Hollis sent Walter Bell to Kenya for a covert assignment. He ended up within the inner circle of Kenyatta’s intelligence.

The writer, Jimmy Burns, claims Bell advised the British governor, Malcolm MacDonald, to “speed up plans for Kenyan independence, believing…that the longer the wait, the greater the risk of radicalisation among African nationalists.”

Burns relied on private archives of the intelligence officer — including his notes, diaries, and letters — to add credence to growing views that the British opted to work with Kenyatta after realising he was moderate and they had misjudged him.

By sending a spy to befriend Kenyatta, Hollis was continuing with a mission he had started as a junior officer. When Kenyatta stayed in the UK, Hollis was assigned to the head of the Security Service’s F-Division, responsible for identifying and tracking ‘subversive activities.’

He was in charge of secretly monitoring Kenyatta. Interestingly, during the August 1963 Lancaster talks, Hollis met with Kenyatta at the Security Service’s headquarters in Leconfield House, Mayfair. They even talked about Bell — though it is unclear whether Kenyatta knew about the covert assignment.

The MI5 first used unorthodox means to collect information on Kenyan politicians attending the Lancaster conference meetings that discussed the future of the post-colonial state. The MI5, the book says, bugged the African delegates’ rooms as they plotted on how to shepherd the new country towards their interests.

Bell had arrived in Nairobi for the second tour of duty with a set agenda: to befriend Kenyatta. He also believed that the colonial administrators had mismanaged the politics.

After he arrived in early 1963, he wrote back: ‘This country [Kenya] has been disastrously mismanaged ever since the [Mau Mau] war, largely because officials never came to terms with African nationalism, and never admitted that the Kenyan African was a human being who was potentially his equal and entitled to be treated with consideration and respect.”

Bell also befriended Kenyatta’s daughter, Margaret, and, perhaps, used that rapport to reach Kenyatta. Due to this closeness, he was asked to stay in Kenya until his retirement in 1967. Kenyatta trusted Margaret more than any other personality in the early years after he returned from jail.

Bell and his American wife, Tattie, seemed to know this and developed a close rapport with Margaret, their neighbour. Whether they had deliberately rented a house near Margaret’s is unclear, but that they supported Margaret in her campaign indicates MI5’s entry point in Kenya’s national politics.

“Tattie won the trust of the politically active Margaret when she played a leading part in Kanu women’s branch by supporting Margaret’s campaign to improve the lives and rights of African women,” says the book. “Bell’s careful personal nurturing of Jomo Kenyatta and his daughter Margaret produced its dividend when Bell was asked to stay on in Nairobi until 1967 to continue the good relations he had established with the African leader in a ‘cover’ role of counsellor, British High Commission,” the book reveals.

Whether the British manipulated Jomo from that position of trust is unclear, but in 1964 and 1965, there were fears about the Soviets and Chinese efforts to topple unfriendly African regimes. This plot was either real or imagined.

The MI6 had also recruited Kenyatta’s minister for Agriculture, Bruce Mackenzie, and he was “involved in setting up the foreign service aspects of the Kenyan National Security Executive”, according to the book. Bell would later start working for this unit.

Whether Kenyatta knew that these were British spies within his office is unclear. But the book reveals that Bell was in 1967 given a formal post of secretary of the new Kenya National Executive Council, described as “Kenyatta’s overarching law enforcement and intelligence arm, which reported directly [to him]. By this time, the relationship between Kenyatta and the MI5 is described as ‘even closer.’

Also Read: Uhuru shatters spy chiefs’ hopes

Bell had won this trust by giving Kenyatta some of the intelligence the British had collected. One of them was a rumour: In April 1965, the book says, “rumour of a potential Soviet-backed coup in Kenya by vice-president Oginga Odinga reached British intelligence via secret sources.” They shared this information with Kenyatta.

We know from other British intelligence reports that the British had formed a propaganda unit known as the Information Research Department whose task was to discredit Cold War enemies — among them Kenyatta’s vice president, Odinga.

The British, worried about his left-wing sympathies and open relations with the communist bloc, started this campaign to undermine Odinga’s place in Kenya’s politics.

By the time Odinga was targeted, Bell was in Nairobi and had managed to win Kenyatta’s trust.

Though the book does not mention this propaganda unit — which was revealed in papers declassified last year — it is interesting that it coincided with the period that Kenyatta was informed that Odinga was plotting a coup.

Eighty copies of a propaganda pamphlet were produced by that unit in September 1965, and given to various journalists.

Then President Daniel Arap Moi (centre) pictured after a past Jogoo House meeting with the permanent secretary in the Office of the President, Mr Geoffrey Kariithi (second right); Maj. Gen. J.K. Mulinge (second left); Director of Intelligence Mr James Kanyotu (left) and Commissioner of Police Mr Benard Hinga.

The pamphlet attacked Kenyatta’s government as “reactionary, fascist and dishonest” and praised Odinga as “a great revolutionary leader” who would seize power through the “newly formed People’s Revolutionary Kenya Socialist party”.

This information about the Odinga coup had been passed over to Kenyatta by Bell. It worked. Kenyatta was frightened of a possible military coup, engineered by the communist countries, and he secretly asked the British, “with Bell as a key conduit…for assistance in the form of military support if a coup was attempted,” says the book quoting Bell’s private papers.

According to the book, “The British responded by making an extensive military plan to intervene, code-named Operation Binnacle.”

This happened between 1964 and 1965. It was Bell who reported in April 1965 that the Soviets had infiltrated the Kenya News Agency and that some Kenyan students had been sent to communist countries to study journalism.

More so, there were attempts to “turn the Kenya Government Information Services into a vehicle for communist influence and propaganda. By this time, the Ministry of Information was in the hands of Ochieng Aneko, an ally of Oginga Odinga.

Both were known to harbour communist sympathies. The MI6 are said to have provided Kenyatta with intelligence on Somalian intentions.

“Bell respected and worked well and closely with the British high commissioner in Nairobi, Malcolm MacDonald, who in turn saw Bell as an experienced intelligence and security officer who had worked hard on winning the trust of Kenyatta and was well informed and prescient in his advice,” the book says.

While it has previously been acknowledged that the British were involved in collecting intelligence on the Shifta crisis, the book says that this has been understated: “The British security and intelligence officials including Bell were actively involved in shoring up the Kenyatta regime, by helping him monitor and disrupt his political rivals and thwart Somali incursions in the country’s North-Eastern Province.”

To manage the colonial transition, the British retained MacDonald as the governor-general between 1963 and 1964 and as the first British high commissioner in 1965.

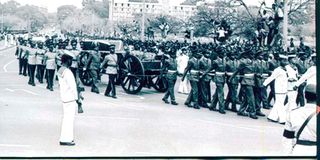

Mzee Jomo Kenyatta's funeral procession by Kenyan soldiers in 1978.

The book reveals for the first time that, when MacDonald arrived in Nairobi in 1963 and as the last colonial governor, “he drew on Bell as his eyes and ears and a discreet negotiator who could help him keep Kenyatta on side.” It is the duo of Bell and MacDonald who are said to have shaped the perceptions in London about Kenyatta. But more than that, Bell is credited for “moulding Kenyatta’s security policy and making it more favourable to British interests.”

During this period of positive feedback, the Britons started to look at Kenyatta as a leader whom “British governments should seek to cultivate good relationships.”

Bell’s return to Kenya in 1960s was the second. He had been sent to Nairobi in 1949 when Kenyatta had just jetted back from a 16-year tour of duty in Europe.

An interesting aspect of the intelligence is that, though the British openly depicted the Mau Mau as savages, they knew it was the direct result of their failure to accommodate African soldiers after the Second World War. The author says that the colonial governor, Phillip Mitchell, had admitted that a mistake had been made and that “it was too late to remedy.”

Another failure was on British failure to court Jomo Kenyatta after he returned from Europe. Bell wrote that the British were ill-equipped to deal, politically and diplomatically, “with such a sophisticated leader of a nationalist movement.”

Rather than engage with Kenyatta, “the colonial authorities treated him like a pariah, blocking him from entering the Legislative Assembly.” Rather than act on Bell’s positive reports on Kenyatta, Bell was transferred from Kenya in February 1952 just as the Mau Mau erupted.

A State of Emergency was declared in eight months as a crackdown on rising African nationalism started. The British would later bring Bell back to Kenya to manage intelligence on Kenyatta.

The Life and Times of an MI6 and MI5 Officer is published by Chiselbury Publishing, a division of Woodstock Leasor Limited in the United Kingdom. It is based on the private papera of private papers of Walter Bell, CMG and US Medal of Freedom and is available worldwide.