Former President Mwai Kibaki leaves Consolata Shrine in Nairobi on September 25, 2016, after attending Sunday Church Service.

“You do not have to blacken the other fellow in order for you to shine. You can shine very brilliantly, and the other guy can also shine very brilliantly. This business of being jealous and envious is ridiculous. It is a mark of smallness of mind and spirit. It is only people of very small minds and spirits who think that they can only shine if the other fellow is totally blackened.” Mwai Kibaki, September 1984.

August 26, 1978, Red Bull Restaurant, Nairobi: It was at night. At a corner were two bosom friends, Attorney General Charles Njonjo and Finance minister Mwai Kibaki. As the country mourned Jomo Kenyatta’s death, the two had taken refuge from their grief and were drowning their sorrows. As they prepared to depart, the proprietor, an old and trusted confidant of Njonjo, posed a question, his voice tinged with concern: would everything be alright?

“Don’t worry,” Njonjo responded with calm assurance, “Kibaki is going to look after us.”

Kibaki was one of the front-runners in the race for number two and had been one of the prime supporters of acting President Daniel arap Moi. Within 90 days, Moi would offer himself for election to succeed Kenyatta and choose a vice-president. He was spoilt for choice, especially within the Kibaki-Njonjo axis.

Before assuming the presidency, Moi had to navigate political schemes orchestrated by the "Change the Constitution" faction, which emerged in 1976. This group sought to amend the constitution to prevent the vice president from automatically succeeding the president if the office became vacant. Their efforts were specifically aimed at blocking Moi’s path to power, fearing his eventual rise as Kenyatta's successor. But after Moi was sworn in by Chief Justice Sir James Wicks at State House, Nairobi, even those who were privately gunning the position retreated.

Then President Mwai Kibaki during the promulgation of the Constitution at the Uhuru Park grounds in Nairobi on August 27, 2010.

“There is no truth whatsoever in the rumours spreading abroad that I or any respectable politician I know of in this stable land of ours will be opposing the President,” said Mbiyu Koinange in a statement. From that, it seemed that the Njonjo-Moi-Kibaki faction had won.

As Moi’s biographer, Andrew Morton, acknowledged, Moi’s “choice of Mwai Kibaki as Vice-President was both an acknowledgement of his political debt to his colleague and an acceptance of the political realities; namely, that the largest, most influential and well-entrenched tribe demanded a place at the heart of government.”

Rivalry between Njonjo and Kibaki began almost immediately, with two distinct political factions forming.

In October 1980, Kibaki summoned the press in Nairobi, voicing his frustrations with certain politicians who were attempting to tarnish his reputation, subtly suggesting he lacked fervor in opposing tribal organisations. Kibaki, just two years into his position, had ascended without the backing of the influential Kiambu political elite, who had long sought to obstruct his rise.

The question of who desired Kibaki’s ouster barely two years into his tenure was part of the complex politics of Kenyatta's succession. By 1980, Kibaki found himself entangled in a shadowy campaign of whispers, marked by growing tensions with Attorney General Njonjo. Rumors swirled that Kibaki might soon depart for a post at the World Bank, adding to the uncertainty of his position.

It is now known that factions had begun to emerge within Moi's fledgling administration. "Kibaki was clearly anxious," Njonjo later recounted to Andrew Morton, the biographer of Moi. "He feared I would take his job. But I was content with the role we had agreed upon. I had no desire for the Vice Presidency."

Mr Charles Mugane Njonjo, the former Attorney-General.

According to Njonjo, their animosity took root the day he visited Kibaki at his Muthaiga home to inform him that he and President Moi had agreed to appoint Kibaki as Vice President. "From that day on, Kibaki became my enemy," Njonjo later remarked. This conflict was not merely a clash of egos; it was also about Njonjo’s attempt to elevate his role as Attorney General above that of the Vice President. By claiming to have recommended Kibaki for the position, Njonjo implied that Kibaki’s appointment was a personal favor, positioning himself as the true power behind the vice presidency.

Njonjo was still eyeing the presidency and two people stood on his way, and they had to be fought, Kibaki and Cabinet minister Jeremiah Nyaga. By then, the radical Jaramogi Oginga Odinga had been silenced. The well-coordinated attack on Nyaga over maize saga was part of these efforts. Nyagah said as much. "They can try to get rid of me through the paper, they can exert pressure on me to resign, but I will not be moved," he vowed.

The next to fall under Njonjo’s instigation was Kibaki. The Standard began publishing a series of critical articles targeting Kibaki, casting a shadow over his previously composed and unflappable demeanour. In response, a visibly agitated Kibaki addressed Parliament, urging MPs to place less stock in the narratives spun by newspapers. "It is we," he declared, "who have worsened the situation by becoming overly dependent on them."

In a stinging rebuke, likely aimed at Njonjo through the figure of George Githii, Kibaki added, "There is nothing extraordinary about being an editor or chairman of a newspaper."

Githii, ever ready to retaliate, fired back through an editorial in the Standard, remarking caustically, "Equally, there is nothing special about being a vice-president either."

These fiery exchanges between the vice president and a leading publication were not mere editorial disagreements; they were orchestrated by political forces behind the scenes. Njonjo’s sway over the Standard was unsurprising, given his longstanding relationship with Githii, who had proven a loyal ally in this political skirmish.

Former Attorney General Charles Njonjo during an interview at his Westlands office on May 15, 2015. He died on January 2, 2022.

When Moi decided to get rid of Njonjo, Kibaki led his supporters in the attack and told Parliament that the traitor would be “shown no mercy.” It was during this period, after Njonjo’s eventual fall, that Kibaki made the statement: “You do not have to blacken the other fellow in order for you to shine. You can shine very brilliantly, and the other guy can also shine very brilliantly. This business of being jealous and envious is ridiculous. It is a mark of smallness of mind and spirit. It is only people of very small minds and spirits who think that they can only shine if the other fellow is totally blackened.”

He also told Parliament that "If there are any subversive elements remaining, we shall continue to take action against them… You cannot belong to Kenya if you cannot owe loyalty to the Head of State."

By then, Moi had put off Kibaki’s critics. While Njonjo was humbled through the Judicial Commission of Inquiry, it was Kibaki’s men who had an upper hand. But not for long.

The attack came from his Nyeri backyard.

It did not escape the discerning gaze of observers that Kibaki found himself besieged in Nyeri, where Waruru Kanja sullied the reputation of Kibaki's intimate ally, Isaiah Mathenge, labeling him a “home guard.” Among those who would openly assail Kibaki was the Nakuru Kanu supremo, Kariuki Chotara, yet such attacks merely served to fortify Kibaki's standing.

As the 1985 KANU elections approached, these assaults on Kibaki became markedly brazen. Foreign Minister Elijah Mwangale emerged as one of Kibaki's most strident critics, making conspicuous visits to Nyeri, bearing gifts and funds, as he sought to supplant Kibaki as vice president.

Kibaki derided such figures as mere ‘political tourists’, yet the onslaught against him showed no signs of abating. In April 1986, a faction of Luhya MPs openly denounced Kibaki in Parliament, intensifying speculation that Mwangale might indeed replace him as vice president. Still in 1986, Nyeri politician Waruru Kanja orchestrated the first convention of ex-Mau Mau fighters since 1964, with the express aim of discrediting Isaiah Mathenge, the KANU Nyeri branch chairman, a former Home Guard and staunch ally of Kibaki. Kanja’s endeavours were lavishly funded, and the State’s partiality towards Kibaki’s opponents was unmistakable. Nevertheless, Moi’s reliance on Kikuyu ex-Mau Mau figures like Kanja and Kariuki Chotara proved ephemeral, as the spectre of the Mau Mau uprising no longer held sway in the political landscape of Central Province.

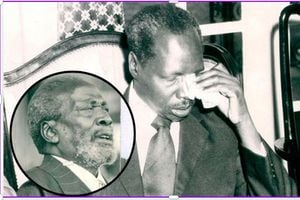

Former President Mwai Kibaki on May 18, 2018. He died on April 21, 2022.

Although Kibaki was spared the public vilification and humiliation that had befallen Moi and later Karanja, his authority was systematically stripped, and his political activities were largely confined to his home district. His close allies, too, were subjected to mounting pressure as they lost their banks and financial institutions. In January 1988, for instance, Moi unceremoniously removed Kibaki loyalist Eliud Mwamunga from the Cabinet.

By then, it had become increasingly evident that Kibaki was destined for removal after the forthcoming general election, as he was no longer perceived as possessing a national persona, an unfortunate consequence of the relentless onslaughts against him. He was regarded as insufficiently fervent for the establishment, for he scarcely mounted a defence against his assailants.

On 24 March 1988, Vice President Mwai Kibaki was unceremoniously demoted to the comparatively minor Ministry of Health. Kibaki chose neither to resign nor to voice any public dissent. The realm of elite politics had become increasingly perilous, and such a defiant move could have carried grave consequences. Josephat Karanja was appointed as the new vice president, simultaneously taking on the role of Minister for Home Affairs.

Tomorrow: Dr Karanja: The man in a hurry