Former President Daniel arap Moi leaves the AIC Kabarak Community Chapel after attending a church service on April 27, 2014.

| File | Nation Media GroupNews

Premium

Revealed: Moi bodyguards were trained by British special forces

President Daniel arap Moi’s bodyguards were trained by the British SAS in 1985 amid a crackdown on dissent, Declassified UK has found. It came as Moi entrenched a one-party state by rigging elections and arresting opponents.

Although UK diplomats knew Moi was subverting Kenya’s democracy, British commandos from the elite Special Air Service were allowed to coach his personal escort team. Moi’s minders were drawn from Kenya’s General Service Unit (GSU), a paramilitary police force long accused of torture and executions.

SAS training was in demand from foreign governments around the world following their televised rescue of hostages at the Iranian Embassy in London. African presidents were particularly keen to receive their expertise on internal security.

Formerly classified British government files show Moi grew increasingly paranoid after a coup attempt was foiled in 1982. To avert further unrest, Moi stacked the GSU with members of his own minority tribe, the Kalenjin, and called in SAS instructors.

Colonel Roger Southerst, a British military attaché in Nairobi, wrote in a confidential memo that the President’s Personal Escort was “responsible for guarding the President both in Kenya and abroad. In 1985 they received continuation training from 22 SAS. Previous to that they had been trained by the Israelis.”

Another British diplomat stationed in Kenya, Howard Pearce, observed that same year how members of Moi’s tribe were being recruited to the GSU “out of all proportion” to their actual number. He noted: “This massive bias clearly reflects Moi’s keenness to create a GSU tribally loyal to himself”.

Pearce’s colleague, fellow diplomat Richard Tauwhare, commented similarly: “The change in the tribal balance, particularly in the [GSU], has been marked with Kalenjin recruitment and promotion running well beyond their relative tribal share.”

He added: “There are also regular allegations and rumours, though never substantiated, of police brutality; and their habit of shooting first and asking questions later is not something a purist on human rights would overlook.”

British aid was complicit in some of these abuses, having gifted Kenya £1.5 million in 1983 to buy 90 Landrovers and communication gear for police intelligence and GSU riot control teams.

As well as bolstering the police, Moi consolidated his control of the Kenya African National Union (Kanu), the country’s only permitted political party. Reflecting on the results of a rigged Kanu poll in 1985, Pearce wrote: “As widely anticipated, Moi got what he wanted. He looks more and more like a typical African dictator, even if rather more benign than most”.

To fix the vote, there were “District Commissioners resorting to tactics such as locking candidates into their houses; arresting them overnight; barring them on ‘technical grounds’; and even not holding elections at all but simply reading out the victor’s name from Moi’s list.”

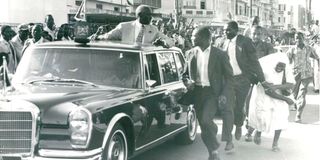

A Catholic nun, who wanted to greet President Moi, is pulled back by security officers. She was among the crowd cheering the President as he reached Sega Market in Mombasa during one of his past coast tours.

Overall, the diplomat felt: “Moi has demonstrated his ability to stifle dissent, and the substance, if not the trappings, of democracy in Kenya becomes more shadowy by the day.” Moi would go on to rule Kenya until 2002.

Support from the West

Dr Willy Mutunga, a former Chief Justice of Kenya, told Declassified: “The West supported the Kanu-Moi dictatorship in their economic, political, and military interests. The West did not support the resistance to the dictatorship's subversion of our democracy and human rights”.

He added: “In the 1980s, students and lecturers in both Kenyatta University and University of Nairobi were either jailed or detained without trial for resisting the violation of their academic freedom. The security of tenure for judges and the attorney-general, critical in any democracy, was removed.

“The political space for activities in civil society shrunk except for those organisations and movements that the dictatorship enslaved.”

Mutunga’s bitter recollection of the period is vividly conveyed in the British files. Diplomats like Tauwhare referred to “Moi’s natural tendency towards dictatorship” and “Moi’s fundamentally autocratic style”. The climate meant no one dared to “raise a dissenting voice for fear of ruining their careers”.

This was particularly true in the media, where “Kenyan editors understand well the need for self-censorship,” Tauwhare commented. Since the 1982 coup attempt, “the press has exercised rigorous self-censorship, pointing up the occasional obvious scandal…but scrupulously avoiding any criticism of Moi or his favourites.”

Otieno Mak’Onyango, an assistant editor at the Sunday Standard, was detained after the failed coup and allegedly beaten by the GSU. Another to enter captivity was Stephen Muriithi, a former deputy intelligence director and business partner of Moi.

Nigel Wenban-Smith, a British diplomat, wrote how Muriithi “knows far too much about Moi and it is doubtful that Moi would ever feel safe to let him free.” Both men sued for compensation upon their eventual release.

Raila Odinga, the son of former Vice-President Oginga Odinga, was also detained after the coup and allegedly tortured by the GSU. He was not released until the late 80s. His family came from the Luo tribe, which British officials felt “operates to a large degree outside the mainstream of Kenyan politics” due to its “relative geographical isolation from Nairobi”.

Queen Elizabeth II and former President Daniel arap Moi acknowledge cheers from the crowds lining the route to State House Nairobi during the Queen's visit in 1983.

Other political prisoners included Maina wa Kinyatti, a history lecturer at the University of Nairobi who specialised in researching Kenya’s Mau Mau rebel movement. Kinyatti had been sentenced to six years imprisonment in 1982 for possessing a “seditious publication”, titled “Moi’s Divisive Tactics Exposed”.

Amnesty International highlighted his detention at Kamiti maximum security prison, where he was held often in solitary confinement and with the cell light constantly on.

Moi was even concerned about opponents who had fled abroad. At a meeting with Conservative foreign secretary Malcolm Rifkind in January 1985, Moi “went on to criticise vehemently the activities of Kenyan dissidents in the UK, particularly Ngugi Wa Thiong'o, who was employed by the GLC (Islington Council). He was pumping letters back to Kenya, with the aim of starting up a Communist Party.”

Thiong'o, a leading novelist, was engaged in such seditious behaviour as holding a play in London called “The Trial of Dedan Kimathi”, referring to the Mau Mau leader executed by Britain. Wenban-Smith commented how: “The Kenyan government is concerned, not to say obsessed, by the activities of Ngugi Wa Thiong'o. We have told them that we could keep a lookout but cannot, of course, do anything unless he breaks the law.”

Wenban-Smith went on to wonder: “But what does ‘keeping an eye’ on such people consist of? Would it be possible for me to have some briefing on the amount of time and resources the Security Services and/or Special Branch are able to spare for individuals like Ngugi?

“I am only too conscious that my department produces quite a lot of ‘clients’,” he added, before listing dissidents from other East African nations. It is unclear from the files seen by Declassified whether MI5 or police were tasked with monitoring Thiong'o.

However the SAS training for Moi’s bodyguards was given that same year and by 1987 a four-man British army training team was stationed at GSU headquarters.

The British major leading that team had a “warm relationship” with the GSU commandant, Erastus M’Mbijiwe, despite his unit’s brutal reputation. M’Mbijiwe is described in British files as “an influential man who has direct access to the President”. This meant the UK training had “a very important political spinoff”.

Although the commandant was “very pro-British”, he had “crippling budgetary problems” and expected UK training to be provided for free, otherwise “we will lose out as the Israelis are waiting in the wings.”

British interests

Britain’s High Commissioner to Nairobi, Sir Leonard Allinson, was willing to overlook Moi’s intolerance of playwrights and historians. Writing in a report, Allinson said Moi was “mercifully no tyrant, rather a stern headmaster” and “Kenya still stands as one of the best run and humane societies in Africa.”

A jovial President Moi shares a joke with an equally delighted Mzee Ali Tanaasi, from Riruta as a security officer restrains the man from embracing the President at the Jomo Kenyatta International Airport upon his arrival from Kuwait in 1981.

British strategy was “to encourage his more liberal instincts and assist promptly…when he [Moi] calls upon us to strengthen through advice and training some of the country’s key institutions, notably…the armed forces.”

Kenya remained the largest recipient of British aid in Africa, receiving £38m in 1985. Rifkind told Moi he was “grateful for the facilities provided for military exercises” that allowed thousands of British soldiers to train annually in Kenya.

A UK foreign minister, Cranley Onslow, regarded Moi as “our staunchest ally in black Africa”, with the President portraying himself to British officials as “a bastion for the west surrounded by hostile Marxist or socialist states.”

British aid was specifically intended to ensure Kenya’s economic woes did not “grow to the point where she loses her standing and influence: still less that her stability and pro-Western alignment be threatened.”

UK diplomats were conscious: “We have significant commercial interests there, and there is a large British community of 24,000” – many of whom were former settlers who stayed behind after independence.

Although some land was transferred from Europeans to Africans post-colonialism, Kenya’s most fertile regions remained under British commercial control.

The country’s major export, tea, stayed largely in the hands of UK firms, with Unilever acquiring key plantations from British settlers in 1984 that are used to grow leaves for PG Tips and Liptons.

Phil Miller is the chief reporter for Declassified UK