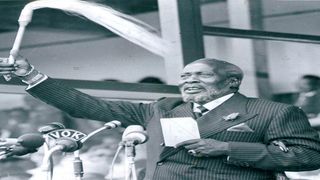

Former President Mzee Jomo Kenyatta.

| File | Nation Media GroupNews

Premium

David Silverstein: Why two doctors were detained after Kenyatta death

What you need to know:

- This is the first instalment of a five-part serialisation of ‘Heartbeat: An American Cardiologist in Kenya’ by Dr David Silverstein.

- Dr Silverstein writes about failed attempts by two doctors to save Mzee Jomo Kenyatta’s life and how Moi manoeuvred intense succession intrigues to rise to power.

As word spread there was a new cardiologist in town, I began to attract private patients from among Kenya’s political elite even though I was still a government employee.

In due course many of them became friends as well. And so I came to learn about the impact of personality on politics and politics on personalities.

In other words, I was witness to the high-level power dynamics that took place behind the scenes. Fifteen years into independence, the political landscape was shifting in unpredictable ways.

I soon found myself caught up in these changes. They were to influence the future course of my life.

Two weeks before my arrival in Kenya in 1974, President Jomo Kenyatta was re-elected for a third five-year term.

He had overseen a peaceful transition in 1963 from British colony to nation state and was respected as the country’s founding father. He had ruled with a firm grip, keeping tribal antagonism at bay even though many felt his fellow Kikuyus had benefited disproportionately from the fruits of freedom.

Many of his colleagues had entrenched themselves in positions of political and economic power. But by then he was about seventy-seven and the question of succession was simmering below the surface. Kenyatta’s running mate, Daniel Toroitich arap Moi, had served as the vice president since 1967.

He had forsaken his chosen vocation as a teacher in 1955 when he gave up his position as a headmaster to be elected to the colonial Legislative Council.

Also Read: Unsung hero who saved Jomo Kenyatta

He had been appointed as the vice president at the suggestion of the attorney general, Charles Njonjo, to replace Joseph Murumbi, the former foreign affairs minister, who had resigned.

Moi was an intriguing character. He was a devout Christian born in a mud hut who rose to becoming one of Africa’s leading statesmen.

When I later got to know him as a friend and saw him on a regular basis, I could see how his deep faith informed his politics.

He felt God’s presence as a steady hand on the tiller when navigating the crosscurrents of tribal and factional power play.

Often he turned to passages in the Bible to help him make difficult decisions. Even after many decades in politics, he still thought of himself as a preacher.

On visits back to his rural home occasionally he would appear in church dressed in a loose shirt and slacks to play the guitar and sing hymns to an admiring congregation.

It was three years later in 1977 when I lost my political innocence. Dr Ramesh Desai, an internist in Mombasa, informed me that Moi had recently been to see him complaining of headaches.

Desai said his examination showed that Moi suffered from high blood pressure. He had advised the vice president to see a cardiologist and had recommended me. Moi soon made an appointment through his secretary Mrs Smith.

I was still a university (of Nairobi) employee and had no private office. It was arranged that he would meet me in the cardiology office next door to the cardiac cath lab (catheterization laboratory) at Kenyatta National Hospital.

First impressions remain in your memory. I can still recall vividly how Moi walked briskly into my office tall, erect and broad shouldered.

Former Presidents Jomo Kenyatta, Daniel Moi and Mwai Kibaki with the first African Clerk of the National Assembly, Mr Leonard James Ngugi.

He greeted me with a firm handshake and a charming smile. He was a vigorous man, handsome in his way, who came across as someone much younger than his fifty-plus years. He was meticulously dressed in a suit. I liked him straight away.

Moi deferred to me when we talked about his heart. Had he had a problem before? Bado (not yet). He made it clear that I was in the driver’s seat even though he was accustomed to being in charge. His English was halting and didn’t flow easily.

It was a habit he’d cultivated to his advantage. It gave him time to think so that often when speaking in public arenas - and behind closed doors too – his statements were intentionally ambiguous. I was to be witness to this diplomatic sleight of hand whenever he discussed Iran or Libya with the Israelis.

I did a complete assessment, including an ECG (electrocardiogram) and cardiacfluoroscopy (as we still did not have echocardiography available in Kenya).

He had trouble keeping his balance on the treadmill as lots of patients do. The vice president’s issues, including his headaches and a thickened heart muscle, were all related to his blood pressure.

I reassured him that his condition could be treated with drugs, which I would prescribe.

As I walked Moi to his car, Hillary Ojiambo saw us together and approached. I felt uneasy in his presence. Hillary had become a professor and, as chief of the department of medicine, was now my boss. He greeted Moi warmly but pointedly ignored me.

I shrugged it off as just a petty gesture until I received a telephone call back at the office from Jerry (Jeremiah) Kiereini, Permanent Secretary for Defence. His wife Eunice Muringo Kiereini was Kenya’s first Chief Nursing Officer in the Ministry of Health. She had also been President Kenyatta’s personal nurse.

Jerry and I already had a history. Earlier that year I had treated his two-year-old son, Githae, for a heart murmur.

On physical examination, I had diagnosed an atrial septal defect. There was a large hole in his atrial septum with blood shunting from the left atrium to the right atrium instead of going entirely into the left ventricle as it should.

This overloaded the right ventricle, flooding the lungs with excess blood and damaging the lung vessels. This was confirmed by cardiac catheterization. I had arranged for Githae to have surgery at St Thomas’ Hospital in London with Mr Brynn Williams. It had gone smoothly.

Now Jerry was telling me over the phone Ojiambo had called to alert him that an agent for the CIA and Mossad was treating the vice president.

Kiereini had told him, ‘You know, the CIA and Mossad are our friends. And David is a good doctor. He saved my son’s life!’

I was amused and flattered that a junior doctor without his own office was thought to be working for the two most highly respected spy agencies in the world.

The anecdote gave me great pleasure. My doctoring skills had been praised and there had been the thrilling assumption I was a spy.

I was so pumped up about it I decided to do a James Bond entry into my flat. I sprang up the stairs, turned the key and kicked the door open. I tried do a shoulder roll to the floor to miss the hail of bullets from the villains inside but tripped and landed heavily on my elbow instead. I was badly bruised and walked around with a stiff shoulder tendonitis for days.

In the summer of 1977 I was made a senior lecturer.

Unfortunately, the promotion didn’t protect me from Hillary Ojiambo. He continued to criticize and belittle me. Fed up with his bullying behaviour, I took my troubles to Dr Eric Mngola, who had replaced Dr Jason Likimani as Director of Medical Services. I told him about the abuses I’d absorbed in silence from Ojiambo.

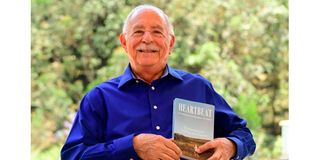

Dr David Silverstain with his memoir ‘Heartbeat: An American Cardiologist in Kenya.’

I’d had as much as I could take. I was thinking of going back to the States. Mngola listened attentively as I poured out my woes then suggested a solution. ‘Why don’t you stay and work for me? I’ll make you the chief cardiothoracic physician in the Ministry of Health.’ He offered me a considerable raise above my current salary.

The position came with a large colonial-style house and garden on Menengai Road within walking distance of the hospital. I said yes immediately. There was another good reason for accepting. I could continue to teach at the university and Eric would shield me from Ojiambo’s vitriol. Many years later I am still grateful to Ojiambo for his affronts. They triggered a career change that improved my life and lifestyle enormously.

The following year in 1978 I went on vacation to Rome. With my Ojiambo issues solved and an important new job ahead, I had decided to celebrate with a brief August holiday in Italy. I arrived in the midst of high drama as Pope Paul VI had died, and the Roman Catholic College of Cardinals were gathered to elect his successor.

Waiting for me at the airport in Rome were my good doctor friends, Robert Thompson and Barney Hecker. I’d known them both at the University of Washington where Bob was an intern and Barney a medical student.

They had since married and joined the US Navy. Before we headed for Naples, where they were stationed, Bob and Barney took me on a twenty-four-hour tour of Rome which culminated at the Vatican. It was an interesting time to be there.

As we entered St Peter’s Square we encountered a large crowd, including a number of press photographers who were aiming huge telephoto lenses at a chimney.

English-speaking journalists in the crowd told us they were waiting for a signal. If white smoke poured from the chimney, the cardinals had chosen one of their number to be the new pope.

If the smoke came out black, they had failed to reach a consensus on who he would be. Though by then we were hungry and keen to leave for dinner, the possibility of witnessing history in the making kept us where we stood, our eyes fixed on the chimney.

Suddenly the smoke appeared, and just as suddenly a debate began. Was the smoke white or black? When viewed against the setting sun, it was difficult to tell.

After some serious squinting Bob, Barney and I decided the smoke was black as did many of the photographers, who started packing up their cameras. The majority of the crowd began to depart the plaza as well.

We left to enjoy a delicious Italian dinner to celebrate my 26 August birthday and then retired to our hotel. Next morning I found an Italian newspaper pushed under my door.

Though I neither read nor spoke Italian, I saw the word ‘Papa’ printed over a picture of what I correctly took to be the new pope standing on a balcony and waving to the crowd.

He was Cardinal Albino Luciani from Northern Italy, a relatively young sixty-four years. He had taken the name John Paul I.

I found it strange that so many of us staring at that chimney had mistaken the smoke’s colour - until I learned we hadn’t. Apparently the chimney was belching black smoke because it was badly in need of service.

What was more, many of the cardinals, their eyes tearing from the fumes, had tossed their notes and tally sheets into the fireplace as they left the room. So we’d seen history after all. We just hadn’t known it at the time.

John Paul I died thirty-three days later in the Vatican’s Apostolic Palace. The official cause of death was a heart attack although conspiracy buffs have advanced many alternate narratives.

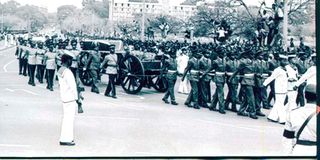

Mzee Jomo Kenyatta's funeral procession by Kenyan soldiers in 1978.

On my way back to Kenya I stopped in London. It was a balmy summer day as I walked down Shaftesbury Avenue in search of a lightweight summer suit. At Piccadilly Circus I passed a news kiosk and did a double take when I saw the headlines.

‘Kenyatta’s death prompts fears of tribal warfare’. The news was no surprise. The eighty-year-old president had suffered from heart problems for more than a decade.

It was said by his inner circle that he had not been actively participating in the affairs of state for the past three years. His refusal to name a successor had led to intense jockeying for position behind the scenes.

The constitution stated the vice president would become acting president for an interim period on the president’s death. After ninety days a presidential election would be held.

Also Read: The fading legacy of Jomo Kenyatta

Moi was from the Kalenjin ethnic group. It was feared by a clique of Kikuyu old guard his accession to power would undermine their dominant position in national affairs.

Their plan was to prevent this happening through a constitutional amendment to introduce the position of executive prime minister. Moi’s position was being safeguarded by another Kikuyu, Attorney General Charles Njonjo. It was a momentous – and dangerous – occasion.

I took the next flight home, eager to see how Kenyans would say goodbye to their first and only president. Would Moi navigate the shoals of succession without incident or would there be a storm of tribal violence as had been predicted? I had come to like Moi while treating him as a patient. I hoped all would go smoothly for him.

In due course I came to know the inside story of what took place. Kenyatta had been found unconscious at 3.30 am on 22 August at State House in Mombasa.

Dr Eric Mngola, who was his personal physician, could not be located. Dr Joel Pinto and Dr J. Wasunna were summoned from their homes in Mombasa and rushed to State House with an oxygen tank. They tried to resuscitate him, but Kenyatta was already dead.

Joel Pinto told me years later that he and Wasunna were immediately detained by the State House security detail to prevent any premature leaks about Kenyatta’s death until it became public. Their families had no idea where they were.

Less than an hour after Kenyatta was pronounced dead Moi’s bedside phone emitted a faint ping as it had been doing, off and on, for weeks. The vice president was at his Kabarak house in the Rift Valley 100 miles to the north of Nairobi.

There clearly was something wrong with the phone, but Moi didn’t know what.

Usually when he lifted the receiver there was no one there, only static.

This time someone was there. Moi told me the familiar voice was Eliud Mahihu, the Coast Provincial Commissioner and a close political ally. The highly agitated Mahihu informed Moi, ‘The eyes of Kenyatta have closed.’ He urged the vice president to depart for State House Nairobi without delay. It was advice that undoubtedly saved Moi’s life.

It had been known for months that Moi was a marked man. He held the home affairs cabinet portfolio as well as being vice president.

After the 1977 elections, he was stripped of much of his power when responsibility for the Kenya Police Service, the General Service Unit (a paramilitary unit formed at independence specifically to ensure peaceful transitions of power), and Special Branch (the state intelligence organ) was given to Kenyatta’s brother-in-law, Mbiyu Koinange, the Minister of State in the Office of the President. Moi was left with the prisons and the immigration department.

It was a clear signal that he was in imminent danger. The instrument of his fate would likely be the Rift Valley Operations Team, known as the Ng’oroko (bandits), a 250-man private army organized by James Mungai, a Kikuyu police commissioner (Rift Valley provincial police boss).

It was funded by the same political foes who had tried to alter the constitution. They represented the Kikuyu ruling elite that had emerged during the Kenyatta presidency. Their mission was to make sure the presidency remained with the Kikuyu. After speaking with Moi, Mahihu informed others of Kenyatta’s death.

Among them was Geoffrey Kariithi, the head of the civil service, who knew of the plot to assassinate Moi. Kariithi phoned the vice president as well, reiterating the message that he should get to Nairobi as quickly as possible. Moi summoned his car and bodyguard/driver at once, and the two headed into the predawn darkness.

They were over two hours away from Nairobi and only a step ahead of his assassins. The Ng’oroko were half an hour behind Moi. He passed through one of their roadblocks without being recognized and made it safely to his Nairobi residence where a General Service Unit detachment was waiting to escort him to State House.

While all this was happening, Moi’s high-powered Kikuyu friend and ally, the Attorney General Charles Njonjo, was in the air on an overnight flight from London. He had no clue what awaited him in Nairobi. On landing Njonjo was escorted to a VIP lounge at the airport to be briefed on the night’s events.

The more he heard, the greater Njonjo’s conviction that Moi’s enemies might go to any lengths to secure the presidency. It was later revealed a plot had been contemplated to murder scores of government officials.

When Njonjo learned that Moi had made it safely to State House, he called Chief Justice Sir James Wicks and asked him to go there at once.

At 3 pm that afternoon, nearly twelve hours after Mzee Kenyatta had ‘closed his eyes’, the Voice of Kenya interrupted its broadcasts with the sombre announcement that the father of the nation was dead.

Three hours after that a group of high level government officials assembled at State House to witness the British-born Wicks swearing in Daniel arap Toroitich Moi as Kenya’s second president.

Two months later Moi named Finance Minister Mwai Kibaki, a Kikuyu from a different faction to that of the late President Kenyatta, as his vice president. It was a shrewd choice that assuaged tribal tensions.

The hallmarks of Moi’s years as vice president had been his championing of education for all, his shrewd competence in discharging his duties in the face of persistent Kikuyu attacks, his comparative honesty and his unerring loyalty to Kenyatta.

Yet once he began to wield the ivory baton he habitually carried in public, the former schoolteacher showed he’d also absorbed a lot about presidential politics during his ten years in the trenches.

His emphasis on reconciliation after the uproar and dislocations of the latter Kenyatta years was well received as was his decision to release political dissidents from prison.

Moi’s masterstroke was to tap into the Kenyans’ love and respect for Kenyatta, who was a venerated legend despite any of his shortcomings as president.

His promise to follow in the great man’s path helped to ratify his legitimacy as Kenyatta’s anointed successor.

He announced an ill-defined policy called Nyayo, or footsteps, implying that he would walk in Kenyatta’s shoes. He later branded the Nyayo philosophy as one of ‘peace, love and unity’. Nyayo became Moi’s sobriquet.

Sometimes people would identify me by saying, ‘Yeye ni daktari ya Nyayo.’ He is Nyayo’s doctor, meaning Moi.

Tomorrow in the Sunday Nation: Kenya’s secret role in the 1976 Entebbe raid that only President Jomo Kenyatta and three other people knew about. Also, romance in a time of terror