Mzee Jomo Kenyatta with members of his family at State House, Mombasa participate in the 1969 national census.

| File | Nation Media GroupNews

Premium

Secrets of the Kenyattas: Hard times and the rise to royalty

What you need to know:

In this first of an exclusive four-part serialisation of Early Bird: A Memoir, Beth Mugo recalls her close personal interactions with her uncle, Jomo Kenyatta, as an unwitting insider in the corridors of power. She was present in his house the night he was arrested on October 21, 1952, witnessed the making of the post-colonial state, accompanied the head of state and First Lady Mama Ngina on official trips and experienced the drama around the death, funeral and succession of the founding president. Also, a deep look into family ties of the Kenyattas

- This is the first of an exclusive four-part serialisation of Early Bird: A Memoir by Beth Mugo

Our ancestral home is in Ichaweri, a small hamlet along an ox-track (now Kenyatta Road) in Gatundu South, Kiambu County.

That is where my father, James Muigai, and his elder brother, Jomo Kenyatta, who later became the first President of the Republic of Kenya, were born.

The area was a hotbed of African independent movements that pushed for access to land for farming and settlement, better education for Africans and preservation of the Agikuyu culture.

Land was particularly a thorny issue due to forced evictions of locals by the colonial government for white settlers in the 1900s.

Historical records give an account of the first evictions in Kiambu where about 10 sub-clans (mbari) were forcibly evicted in Tigoni, an area preferred by white settlers because of its rich soils and climate.

Huts and crops in the area were removed and the displaced moved by the railway in 1919 to work on European farms in Rift Valley as squatters (ruguru rua ngaari).

Also Read: Kenyatta family feuds over land

The resultant tension forced the colonial government to establish the Kenya Land Commission (also known as the Morris Carter Commission) on April 12, 1932, to look into the native land grievances.

Earlier, my uncle, Jomo Kenyatta, had warned the colonial administration of possible violence erupting in the near future should they not rescind their decisions on land.

My birthplace

I was born on July 11, 1939, at Kiambu Hospital, located in the lush green and fertile land of Gatundu in Kiambu County to James Muigai Ngengi and Minneh Ngina…

My father (who was born in 1903 in Ichaweri) was the first boy in Alliance High School, which is considered one of the first institutions in Kenya to offer secondary school education to Africans.

He held the coveted registration number 01 in the pioneer class of 27 students that included Eliud Mathu. In the school records, my father appears as James Muigai s/o Johnstone, an entry made by the founding headmaster GA Grieve.“s/o” stands for “son of" Johnstone (or Jomo Kenyatta, a name he later acquired), his brother who brought him up…

Referred to as “James the First” at his alma mater, my father was the youngest and one of the two siblings of Jomo Kenyatta, Kenya’s first Prime Minister and President (1963–78).

Their elder brother, Kung’u Muigai, vanished without a trace at the age of 13. It is believed wild animals may have eaten him alive in Kiambu forests.

My grandfather, Ngengi, came from Gatundu, while my grandmother, Wambui, was from Kabati in Murang’a.

My paternal great-grandfather, Kung’u, was the son of Magana. We, therefore, identify ourselves as members of the Magana clan (Ambu a mbari ya Magana). The family is about three known generations old. My great-grandfather had many wives.

One of them, my great-grandmother, was captured and brought to Gatundu from the Maasai in the Naroosura area of Narok South Sub-County.

Her name was Mosana, which was changed to Muthana and subsequently Wanjiru to conform to Kikuyu culture.

Mzee’s difficult childhood

My father and Jomo Kenyatta had a difficult beginning. My grandfather, Muigai, had died earlier and his brother, Ngengi, stepped in to take care of my grandmother, Wambui.

That is why Kenyatta was called Johnstone Kamau Ngengi and my father was named James Muigai.

In African culture then, when a man died, his brother or close relative was always assigned the responsibility of taking care of the widow, especially if he left behind small children. In some communities in Kenya, this practice is referred to as ‘widow inheritance’...

Unfortunately, my grandmother fell ill when my father was still an infant. As was common practice, the Kikuyu could not touch the dead. A person who was dying was taken into a nearby forest or hillside and placed in a ngurunga (cave), and left there. A long leash on their right hand would be used to monitor movement and tell whether they were recovering or dying.

At the time, Kenyatta, the second born of my grandmother, was working as a houseboy and cook for the white missionaries at the Church of Scotland Mission in Thogoto, Kikuyu, about 19 kilometres north of Nairobi…

Jomo had left his mother ailing during his last visit. When word reached my uncle, that his mother was critically ill, he sought permission from his supervisors, left the Mission station in Kikuyu and walked to his rural home in Gatundu to establish the condition of his ailing mother, which was a long journey as transport was rare those days.

Unfortunately, his mother had died by the time he arrived and, therefore, he inquired about the whereabouts of his brother, James Muigai, an infant at the time. He was told that his brother, because he was too small or young, had no one to take care of him and was abandoned next to his mother to die.

Angry and sad, my uncle (Kenyatta) took a kiondo (a hand-woven handbag made of sisal and leather straps) and dashed to the forest to look for his brother.

Wild animals had already mauled his mother on one side but the child was still suckling her remaining breast. And that was how Kenyatta rescued his brother. He placed the baby in the kiondo basket and carried him back home. His uncle was unwelcoming and showed no sympathy, locking them out of his house.

However, a determined Kenyatta identified a tree, where he took shelter and spent the night with the baby in the kiondo, to escape the wrath of marauding wild animals from the neighbouring forests.

Without food, Kenyatta struggled to find some cow milk (iria), which he fed the baby. My dad often got emotional when narrating this sad story.

The following day, Kenyatta set off at dawn to look for his maternal aunt, who was across the Thiririka River from Ichaweri village where they were born, a distance of about 1.2 kilometres. Their aunt, Wacu, was living in Gatundu and often traded her wares in the market.

Wacu empathised and agreed to take care of the infant.

Kenyatta returns from UK

Around 1946, we got information that my uncle, Kenyatta, was coming home. He had been away in England for a long time and many of us only knew him through stories told by our parents.

I did not know what to expect, but an air of expectation had been created not only in our home, but the entire Kikuyuland. On arrival, Kenyatta first went to Dagoretti to see his first wife, Grace Wahu, the mother of Peter Muigai and Margaret Kenyatta.

My father travelled from Ichaweri to see his brother but was stranded at the gate because Baba Mukuru (Kenyatta) was in a meeting with members of the Kikuyu Central Association (KCA) who had gone to see him and, perhaps, update him on the developments at home and to receive a brief from him on the progress and challenges he had encountered in England, petitioning their cause to the British Government and Parliament.

Midway, somebody whispered to Kenyatta that his brother had been sighted at the gate. He rose to his feet and dashed to the gate and hugged his brother. They cried and embraced tightly. Margaret Kenyatta, who was present, said it was a sight to behold.

Later, they went to Ichaweri together. That is when I first saw him. He was light skinned and heavily built…he didn’t look 'African' because I was used to seeing dark-skinned people. We vacated our sleeping area, next to the main house, for him because his own house was not ready.

Our interactions were memorable. From our house, straight down was Thiririka River, where we had a pineapple plantation. The river had a ndia, a place of calm waters, where people could swim and enjoy good grass for picnics. He loved picnics and would always treat the whole family. It was something to look forward to.

Kenyatta weds Ngina

In September 1951 my uncle, Jomo Kenyatta, married Ngina Muhoho, the daughter of Chief Muhoho wa Gathecha and Anne Nyokabi Muhoho from Kiganjo in Kiambu. Popularly known as Mama Ngina, she is the first First Lady of Kenya and mother of President Uhuru Kenyatta, Kenya’s fourth Head of State…

Mama Ngina and I have been more than family; we’re close friends. She is our mother and matriarch. Our relationship started early, immediately after her marriage to my uncle. I was sent to stay with her and Baba Mukuru (Mzee Kenyatta) soon after their marriage to give her support as is required under the Agikuyu tradition. She would call me “Mwendi-raha” (joyful one) and I would address her as “Maitu” (mother).

One night (on October 21, 1952), many white policemen stormed Kenyatta's home, flashing torches from all directions. They entered and ransacked Kenyatta’s house before arresting and taking him away. The policemen were wearing khaki shorts, slightly wide black belts and boots. It was a frightening night.

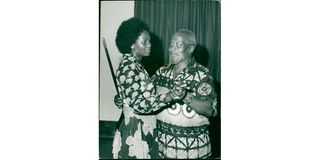

President Kenyatta and Mama Ngina during New Year celebrations in the 1970s at State House, Mombasa

Kenyatta was, however, calm. It was late in the night, but he had remained awake and it looked like he had anticipated their coming.

In the house that night was Kenyatta, Mama Ngina, Jeni, young Kristina Kenyatta and me. There were some of his house staff and farmhands, too. Kristina had just been born.

Mbiyu Koinange and Achieng’ Oneko, who later became Minister of State in the Office of the President and Minister for Information, Broadcasting and Tourism respectively, were regulars to the home, but I don’t remember if they were present. Mama Ngina was a young bride and we did not know where they had taken Kenyatta.

From there on, we never had peace. The colonial askaris (policemen) routinely ransacked the house. Mama Ngina was later arrested and jailed for five years in Kamiti Maximum Prison. Back home, our house was demolished, forcing us to move to the colonial villages, which were shanties built in a row facing each other, and separated by a beaten path. Life was difficult.

My father had also lost his job and did not have a salary and so could not even afford new clothes. I saw him wear patched shorts and Jeni needed our care in the absence of her parents, who were incarcerated. Kristina was taken in by her maternal grandmother in Gatitu, Kiganjo.

Later, I often accompanied Mama Ngina, as First Lady of the Republic of Kenya, to trips, mainly foreign. Besides Elizabeth Mumbi Madoka, her social secretary, I was Mama Ngina’s companion on those trips. My hotel room would always be booked next to hers so that I could attend to her whenever she needed me.

The relationship between Mzee Kenyatta and Mama Ngina planted a seed in me that later germinated into my political life.

*****

During the trial of Kenyatta, there was so much propaganda. We did not know if he would come back. Radios were not common, but there was a state of fear as chiefs mocked our family. Planes flew and dropped leaflets while speakers blared that Kenyatta was a bad man.

From the loudspeakers, they called out: “Come out, you Mau Mau.” Colonial askaris pursued Mau Mau suspects and bundled them into Land Rover vehicles. My father was once hit because he refused to remove his hat.

Then Deputy Prime Minister Uhuru Kenyatta and his cousin Beth Mugo at ICC in the Hague, Netherlands in 2011.

Kenyatta release

After Kenyatta was released, he did something that I considered special, something that enabled reconciliation between the Africans who were deemed to have collaborated with the colonial government, and those who fought the colonial government.

Instead of retribution, Kenyatta invited the men who had betrayed him to his home and shared roasted meat with them openly to signify an end to hostility, and prepare Africans to unite in readiness for Independence.

Also Read: Unsung hero who saved Jomo Kenyatta

In 1962, Kenyatta went to London to negotiate Kenya’s Independence, and in May 1963 he led Kanu to victory in pre- Independence elections. On December 12, 1963, Kenya celebrated its Independence, and Kenyatta formally became prime minister. The next year, a new constitution established Kenya as a republic, and Kenyatta was elected president.

Presidency

As president, Kenyatta faced a powerful pull of interests that piled immense pressure on him. He struggled to resolve three things – How to deal with the European settler community, Africans in the colonial civil service, and the Mau Mau soldiers.

The landed gentry in Kenya in 1963 were largely Europeans who significantly contributed towards Kenya’s food security and foreign exchange earnings through export. Kenyatta’s speech in Nakuru persuaded some, such as Thomas Pitt Hamilton Cholmondeley, the first son of Hugh Cholmondeley, the third Baron Delamere, to remain even as others sold their farms to the government under the Settlement Fund Trustee (SFT) scheme, a land settlement programme launched in 1961 to facilitate smooth exit of settler farmers and resettlement of Africans.

Meanwhile, the Mau Mau wanted Africans who had entered the colonial service, such as Charles Njonjo (Deputy Official Receiver and Crown Counsel, State Law Office), John Michuki (African District Commissioner) and Ezekiel Othieno Josiah (African District Commissioner), to be removed.

Kenyatta explained that the government is a going concern and he needed those Africans in the civil service to help him understand the institutional instruments of governance.

The Mau Mau fighters also demanded to be integrated into the country’s Defence Forces (Kenya Army).

However, Kenyatta declined, perhaps fearing that the Mau Mau generals would dominate and frustrate the professional ranks of the military. Looking back, Kenyatta was right.

Also Read: The fading legacy of Jomo Kenyatta

President Jomo Kenyatta with Vice-President and Home Affairs Minister Daniel Toroitich arap Moi.

My proximity to power

Throughout my childhood, teenage and young adult life, I admired Mzee Jomo Kenyatta...As president, he gave me opportunities to visit him at the State House, a rare opportunity to be close to power. Whenever I happened to be in State House, I would join him for lunch and listen to him speak with senior politicians, diplomats and corporate heads.

Mama Ngina was generous and accommodating. She allowed me to visit Mzee Kenyatta in their Gatundu home anytime. My uncle never lived at the State House. He was, therefore, accessible to us as a father and leader. This was in line with our tradition, where the brother of your father is your father, while the brother of your mother is your uncle. Being older than my father, Mzee Kenyatta presided over all family functions.

Ethiopia trip

On many occasions, Mama Ngina invited me to accompany them on local and international trips. For instance, when Kenyatta graced the 37th coronation anniversary of Emperor Haile Selassie in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, the only foreign trip by air during his presidency, I missed but would have probably accompanied them if I was around. He always travelled by road and Haile Selassie was a revered figure in his country...

I also accompanied them to the countryside, including Embu and Nyeri. On one such trip, we spent the night in Embu at the residence of Charles Karuga Koinange, the then Eastern Provincial Commissioner and, thereafter, the President proceeded to Meru. During this time, Mama Ngina, Elizabeth Mumbi Madoka, other members of the entourage and I remained at Sagana State Lodge. Mzee Kenyatta left us in Embu when he went to Meru and on his return, joined us at Sagana State Lodge after three days.

***

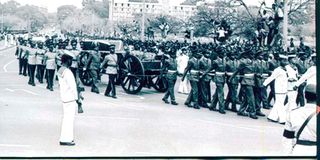

Mzee Jomo Kenyatta's funeral procession by Kenyan soldiers in 1978.

Mzee’s death

It came as a shock when information about his death reached me because he was not sick.

I was in Nairobi in a house we had rented from Joab Omino (former Kisumu Town MP and Assistant Minister for Foreign Affairs), near Vet Lab Sports Club in Loresho, on the night of August 22, 1978, when my mother called to break the sad news. Our house in Kitisuru, Nairobi, was under renovation. I believe Mama Ngina Kenyatta must have called my father in the night with the news.

Earlier that day, we had watched him on Voice of Kenya (now Kenya Broadcasting Corporation) television speak in Msambweni, Kwale, at Bomani Primary School (renamed Jomo Kenyatta Primary School), where he looked okay. Accompanying him at the event were Mama Ngina, his confidant, Mbiyu Koinange, Coast Provincial Commissioner Eliud Mahihu, State House Comptroller, Alexander Gitau and Head of Presidential Press Unit Kenyanjui Kariuki, among others…

However, it is said that half way through the performances at the school in Msambweni, there was a health scare that forced him to end the function prematurely but with his clarion call “Harambee”. There was something different about his voice. It is said this was the loudest roar ever heard from Mzee Kenyatta.

In the call from my mother, I was to prepare to go to Mombasa to be with Mama Ngina. This was around 2.30am in the morning, so I dashed to the Jomo Kenyatta International Airport (JKIA) to catch the next available early morning flight to Mombasa. Nairobi Embakasi Airport had earlier been closed on March 4, 1978.

At the airport, I met Dr Njoroge Mungai, who was the Minister for Foreign Affairs at the time. He was also rushing to Mombasa. However, we did not travel after receiving information that the body of the president and his family would be moved to Nairobi. We decided to wait in the capital. August is a school holiday month and so the entire immediate family members of Mzee were in Mombasa.

Julius Karangi (who later became General), Major General Gichuru and a pilot, Captain Atambo, had been assigned to move the body and Mzee’s family from Mombasa. The two Puma choppers, one for the body and the other for the family, landed in Nairobi Eastleigh Airbase at about 10am.Brigadier Sam Macharia, the president’s aide de camp, accompanied them.

As we waited at the State House, they arrived in an ambulance, carrying the body and three other vehicles, including the one for Vice President Daniel Moi and Mama Ngina Kenyatta.Moses Amonde Oyugi, then Warrant Officer II in the Kenya Army, drove the ambulance.

All this time, I still did not believe my uncle had died. I could not see him dead. I couldn’t imagine or visualise him lying still. It was like a dream. The atmosphere was gloomy and foggy, an indicator that the “eyes of Kenya had indeed closed”…

I remained at the State House throughout the mourning period.

During that time, I would rise early and move from my room with Mama Ngina to where the body lay…

Mzee Kenyatta’s body was placed outside a coffin with his favourite walking stick on the left side and a white flywhisk on the right. His watch was on his wrist, while the huge pinky ring was on the left little finger. Each morning, Mama Ngina put a fresh rose flower on the lapel button of the suit…

I vividly remember the day Jaramogi Oginga Odinga, Kenya’s First Vice President, came to pay his last respects, accompanied by his wife, Mary Ajuma. He walked in wearing what looked like a colobus monkey skin in his left hand and a black fly whisk on his right and recited a dirge in Dholuo, his mother tongue.

When Jaramogi saw Kenyatta’s body lying there, he broke down and shed tears. I witnessed that. Perhaps, he felt “Mzee Kenyatta, my friend is gone before we could reconcile officially.”

And that is a big lesson that we should never hold grudges for too long and learn to forgive and reconcile. It is also the reason I celebrated the Handshake between President Uhuru Kenyatta and former Prime Minister Raila Odinga, the sons of Mzee and Jaramogi respectively, on March 9, 2018.

While they were on opposite sides politically, having competed to clinch the presidency in the 2017 elections, they put aside their differences to unite the country through a “Handshake”. They wanted the country to heal and unite…

Actually, Mzee Kenyatta was working with my brother, Ngengi Muigai, to meet Jaramogi for reconciliation. Two previous appointments to meet Mzee were postponed because of the president’s busy diary.

Unfortunately, Mzee died on August 22, 1978, a few hours before their scheduled meeting on August 23, 1978, at State House, Mombasa.

Ngengi, who was in Nairobi to pick up Jaramogi and his team, had to fly to Mombasa that night after information reached him that Mzee Kenyatta had died.

Succession talk

Events around Mzee Kenyatta’s health and age must have triggered a succession debate.

Around 1976, a renowned South African heart specialist, Dr Christian Bernard, had flown in from Johannesburg to review the president’s condition. It is rumoured that Dr Bernard may have let the cat out of the bag when he broke down during a speech before guests at a dinner in his honour.

The then Director of Special Branch (now National Intelligence Service), James Kanyotu, whose antennae was always up must have picked the ‘emotional’ signal and discussed President Kenyatta’s health with Attorney-General Charles Njonjo and Geoffrey Kariithi, the then Head of Civil Service and Secretary to the Cabinet.

The sensitive dimension of the imminent succession in the face of calls to change the constitution must have cropped up in their discussion, leading to the start of plans for a smooth transition of power in the event Mzee died…

- Tomorrow in the Sunday Nation: My entry into politics