Premium

Fearing the worst, US undocumented migrants brace for deportation

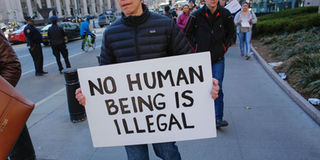

People hold posters as they walk around 26 Federal Plaza immigration court building during a rally, to show solidarity with the countless individuals affected by deportation, March 9, 2017 in New York. PHOTO | KENA BETANCUR | AFP

What you need to know:

- Trump's Homeland Security Secretary John Kelly has said he is prepared to break up families.

- The government has said that although the priority is to capture and deport undocumented immigrants with criminal records, anyone in the country illegally is subject to deportation.

LOS ANGELES

Adriana is preparing for the worst: deportation. She's worked it out in her head, but she still doesn't know how to tell her kids, who are terrified of losing her.

The Mexican-born mother of three began preparations after reading a pamphlet obtained at her son's school in a Los Angeles neighbourhood with many undocumented Hispanics.

It spells out what to do in case of an immigration emergency — a real and growing threat since President Donald Trump arrived in the White House on a promise to expel the 11 million people in the country illegally.

Trump's Homeland Security Secretary John Kelly has said he is prepared to break up families, ratcheting up the pressure for parents like Adriana.

DETAIN IMMIGRANTS

Although there have been no mass deportations since Trump's inauguration January 20, ICE, the agency that enforces immigration rules, has been given broader authority to detain undocumented immigrants.

Everyone is now theoretically on the radar, even those living in a so-called sanctuary city or who are protected under DACA, an Obama-era policy that defers deportation for undocumented immigrants brought into the country as children.

Adriana — who like others interviewed for this story asked that her last name not be used for security reasons — crossed the border into the United States with her parents when she was just six years old.

Although the 31 year-old now enjoys certain protections under DACA, that is cold comfort.

"We don't know. (Trump) is capable of coming and saying it's over, and just like that I lose my work permit," she said.

Adriana has spoken with her American cousins to ask them to take care of her children, who are nine, 10 and 14 years old, if something happens to her or her husband, who also has a work permit.

"The children don't know. We don't want them to be afraid," he said.

She doesn't want to go back to the land of her birth because it is no longer home to her.

"I don't know Mexico. If I were to go, I'd be lost," she says.

ALARM BELLS

Alarm bells went off in Adriana's corner of Los Angeles last week when immigration agents arrested the father of a 13 year-old girl as he was driving his daughter to school.

The girl, Fatima Avelica, captured the arrest on video that soon went viral, sparking street protests.

The agents behaved as if "my dad is a criminal, and he is no criminal," the teenager told AFP.

"He is a hard worker, he came to this state for us, for his daughters, to have a better life so he didn't come to do bad stuff. He's a very good person."

The incident sent shock waves through Fatima's school, Academia Avance, where Adriana's children also are enrolled along with many other Hispanics.

Socorro, the 38 year-old mother of another Avance student, says she's a nervous wreck.

"In the street you can't be calm, you have to be looking around you," she said.

Socorro has lived in the United States for the past 18 years working as a hairdresser. Now she plans to apply for Mexican passports for her children so she can take them in case she is deported.

CONTINGENCY PLANS

Giovani, a 38 year-old restaurant worker whose children also go to Avance, intends to sit down this weekend with his wife Silvia to map out contingency plans.

"The family is going to stay together, either there or here, but it will be impossible to separate us," he says. "It will be a bit hard on the kids because they are very used to the United States, but they'll adapt."

The government has said that although the priority is to capture and deport undocumented immigrants with criminal records, anyone in the country illegally is subject to deportation.

The arrest last week in Seattle, in the northwestern state of Washington, of DACA recipient Daniel Ramirez Medina is a case in point.

Agents had entered Ramirez's house to arrest his father, but took his son into custody after he allegedly confessed to being a gang member. Ramirez, who has no criminal record, denies having said any such thing.

Being in the wrong place at the wrong time is all it takes to run afoul of the immigration authorities.

A recent operation in San Jose, California netted a dozen gang members, but also 11 other undocumented immigrants with no criminal records.

"One never knows now. It can happen to anyone," said Socorro.

She says her 14 year-old daughter knows just what to do if there is an arrest: "Tape it with your cellphone."