Premium

One in six human trafficking victims is a child

DESIGN | BENJAMIN SITUMA

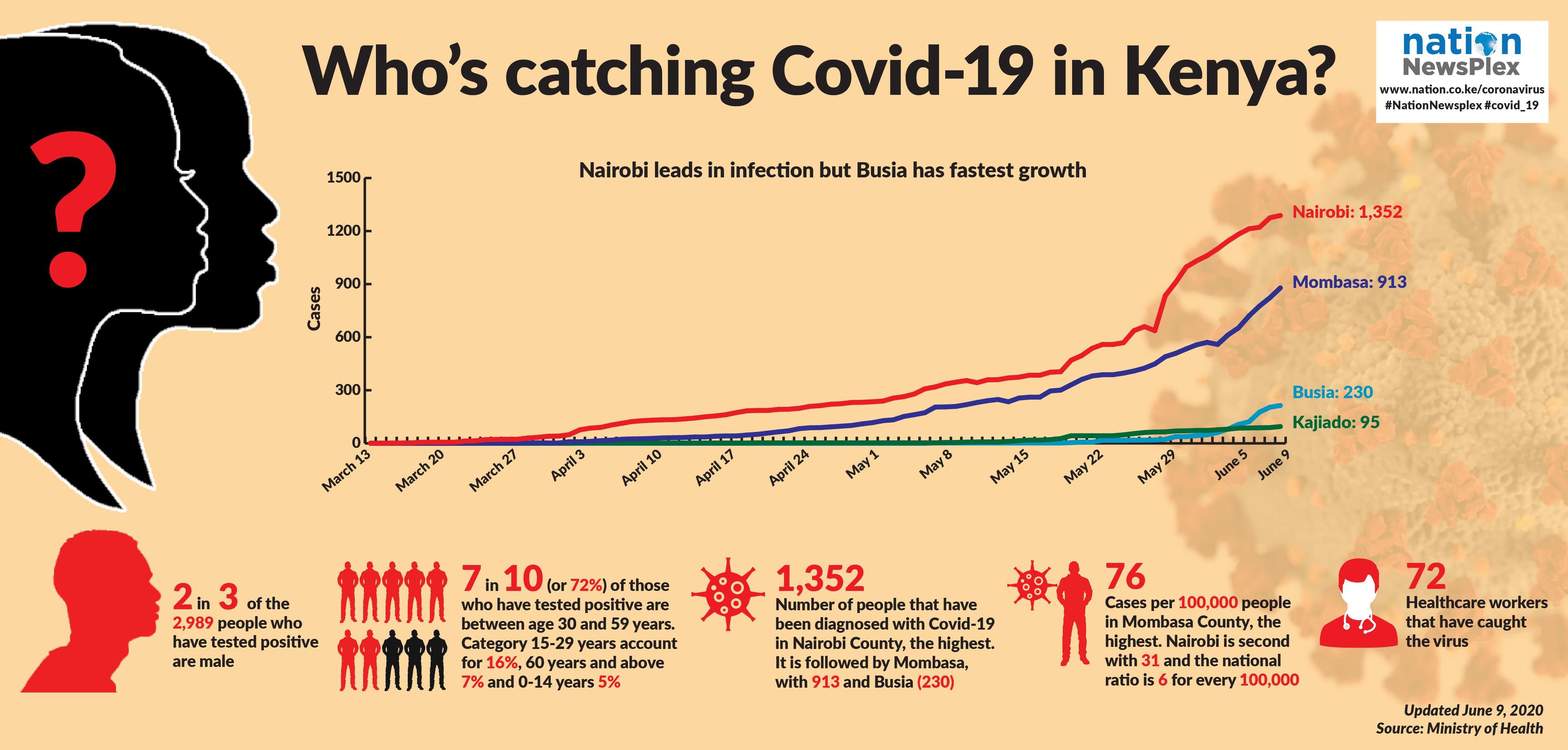

One in six victims trafficked for forced labour, sexual exploitation and other reasons such as begging in Kenya is a child, reveals a NationNewsplex investigation.

Two-thirds of victims of human trafficking, also known as modern slavery, are aged 18-29, another 17 percent are aged between 30 and 47 while less than one percent are over 47 years, indicate figures from the Counter-Trafficking Data Collaborative, a data hub on human trafficking.

Kenya remains a source, transit point and destination for people subjected to sex trafficking and forced labour.

Phyllis Ajwang’ biggest regret in life is her decision to drop out of secondary school, which led her to losing two years of schooling and ending up in forced domestic work.

By the time she completed primary school, Phyllis was not only an orphan but she had also lost her eldest sister, who had stepped in to help her dad take care of her and her six siblings after her mother died. With both her parents dead, another sister struggled to pay her fees from her modest untrained-teacher salary after Phyllis joined Form One at Ahero Girls in Kisumu County. The going got tough and she was often sent home for delaying to pay school fees. Too young to appreciate the sacrifice her sister and guardian was making for her to get an education, Phyllis accused her of not doing enough and they often ended up arguing.

By the time she was in Form Two, frustrated and depressed, Phyllis dropped out and returned to her rural home in Nyakach Constituency. For weeks on end she looked for work in vain. Then one day she met a friend of her late mother who had returned home from Nairobi to visit her parents in the neighbouring village. The woman convinced 14-year-old Phyllis to visit her in Nairobi so she could help her get work. It took her a month to raise the bus fare to the capital city, but the teen finally made it to the family friend’s house.

True to her word, the woman linked her up with a friend who was looking for a housekeeper to start immediately. They agreed on a monthly pay of Sh6,000 and she got down to work, doing the house chores and taking care of her employer’s toddler when she and her husband were at work.

It went on well, and she got her full salary on time until the end of the third month when her employer gave her only Sh1,000 and promised to pay the balance in a few days. But the situation got worse for the next three months as her employer stringed her along and stopped paying her at all. At the same time, the employer did not buy her basics such as bathing soap and sanitary pads and would scold her for no reason even as the work of taking care of the child and the three-bedroom house increased.

After six months on the job, Phyllis managed to call a relative living in Nairobi, using a friend’s mobile phone, who sent her money to pay for the trip back home.

Means of control

The profile of children trafficked is different from the one of adult victims globally, in recruitment, means of control and other aspects of the trafficking process. Figures from the International Organization for Migration (IOM) show that over 40 percent of children were recruited with the involvement of a family member or a relative, compared to nine percent for adults. This means that family participation is four times higher for child victims than in cases affecting adults.

Another 14 percent were recruited by intimate partners while 11 percent were enlisted by friends, as in the case of Phyllis.

Experts say figuring out how victims are recruited by traffickers is key to preventing trafficking, and that children are controlled more through physical abuse and psychoactive substances than adults.

Sadly, Phyllis’s traumatic experience is not unique, as threats, false promises, and withholding earnings and necessities are some of the controls mostly used by traffickers on children and adults, according to IOM.

Humbled by her ordeal, Phyllis returned home and convinced her older brother, who had completed college during her absence and got a job, to pay her school fees. The following year, she joined Bishop Okumu Secondary School to repeat Form Two. On completing her secondary education, she enrolled for an early childhood education teaching course and got a certificate a year later. She is now pursuing a diploma in the same course.

Worldwide, children make up a higher proportion (30 percent) of the detected victims, almost double Kenya’s share, with far more girls detected than boy, states the Global Report on Trafficking in Persons 2018 by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).

As the world marks World Day against Trafficking in Persons tomorrow (Tuesday), and despite the Counter-Trafficking in Persons Act of 2010, Kenya remains a source, transit point and destination for people subjected to sex trafficking and forced labour. What is more, victims may still be criminalised while the impunity of traffickers prevails, according to a 2019 Trafficking in Persons Report by the US Department of State that assessed the commitment of governments to end human trafficking.

For four years running, the US State Department listed Kenya in tier two of four levels for not fully meeting the minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking. Inclusion in the lowest category (tier four) means that a country may lose US aid and be subject to sanctions.

The report, published earlier this year, notes that authorities continue to treat some victims as criminals, and protective services for adult victims remain negligible. There were also no investigations into official complicity, despite credible reports of traffickers obtaining fraudulent identity documents from corrupt officials. The government also routinely prosecuted trafficking crimes as immigration or labour laws violations, rather than under the anti-trafficking laws, which resulted in traffickers receiving less stringent sentences.

Overall, two-thirds of victims exploited in the country are female, against a third who are male.

In Kenya. almost two-thirds of the victims (60 percent) are trafficked for forced labour, with 20 percent facing sexual exploitation, indicate figures from Counter-Trafficking Data Collaborative.

Worldwide, however, the most common form of human trafficking (59 percent) is sexual exploitation, according to the UNODC. The victims of sexual exploitation are predominantly women and girls. The second most common form of modern slavery is forced labour (34 percent), although this may be a misrepresentation because forced labour is less frequently detected and reported than trafficking for sexual exploitation.

Over the last 13 years, UNODC has collected information on about 700 victims of trafficking in persons for removal of organs, detected in 25 countries, compared to 225,000 victims of trafficking in persons for all other purposes. In general, the pace of the crime is dictated by the shortage of organs on the global market, as the availability of donated organs is limited and overshadowed by demand.

Ethiopians and US

Almost three-quarters of local victims are Kenyans, followed by Ethiopians (nine percent) and other nationalities (21 percent). While Ethiopia tops as a source of foreigners exploited in Kenya, the United States is the main destination of Kenyans trafficked out of the country. Still, according to Counter-Trafficking Data Collaborative, more than half of Kenyans (55 percent) are trafficked locally, while about 18 percent are trafficked to the United States.

Launched in November 2017 the database that combines the three biggest case-level human trafficking datasets from IOM, Polaris and Liberty Asia to develop one centralised dataset has information on about 90,000 records of victims of human trafficking of 169 nationalities exploited in 172 countries.

The US State Department report finds that some Kenyans are recruited by legal or illegal employment agencies or voluntarily migrate to the United States, Europe, Southeast Asia, and the Middle East — particularly Saudi Arabia, Lebanon, Kuwait, Qatar, the UAE, and Oman — in search of jobs, where at times they are exploited in domestic servitude, massage parlours and brothels, or forced manual labour.

“Nairobi-based labour recruiters maintain networks in Uganda and Ethiopia that recruit Rwandan, Ethiopian, and Ugandan workers through fraudulent offers of employment in the Middle East and Asia. Kenyan women are subjected to forced prostitution in Thailand by Ugandan and Nigerian traffickers. Men and boys are lured to Somalia to join criminal and terrorist networks, sometimes with fraudulent promises of lucrative employment elsewhere,” said the department.

Gold mines

Within Kenya, children are subjected to forced labour in domestic service, fishing, street vending, agriculture, cattle herding, and begging. Girls and boys are exploited in commercial sex throughout Kenya, including in sex tourism in Mombasa. Children are also exploited in sex trafficking by people working in khat (a mild narcotic) cultivation areas by truck drivers along major highways, and by fishermen on Lake Victoria and near gold mines in western Kenya. However, Nyatike sub-county of Migori County, businessmen in artisanal and small-scale gold mining have learnt to exploit children for labour. For the same amount paid to one adult, a gold baron can procure two or three children.

The US State Department report found that Kenya had made improvements in the past year, including commencing digital law enforcement, data tracking on a monthly basis and allocating funding for its victim assistance fund for the first time since 2015.

Kenyan authorities reported identifying and referring to care at least 352 trafficking victims in 2017, of whom the vast majority (267) were subjected to forced labour and seven to sexual exploitation. During the period, the government provided Sh60 million from the national budget for anti-trafficking efforts, including implementation of the National Referral Mechanism and the victim assistance fund.