Retired Kenyan long distance runner John Ngugi poses for a photo on July 18 2024 at the Nation Centre building in Nairobi.

From outrunning a buffalo, Kamlesh Pattni refusing to buy his Olympics gold medals claiming they were gold coloured pieces of metal of no value, telling off a stranger who demanded his urine in front of his wife for a drug test, John Ngugi, known as "King John the First” from his cross country running exploits opens his heart to Nation Sport.

On February 12, 1993 mid-afternoon, a white couple arrived at a wholesale shop on the ground floor of Boston House in Nyahururu town, 190km north west of Nairobi, unannounced, with a very important message.

“Who amongst you is John Ngugi?” the male asked a group of men sitting at a corner in animated conversation, ignoring the lady at the counter, an obvious sign that their mission was not to purchase an item.

One of the men pointed at Ngugi sitting on a high stool at the wholesale shop, who readily stood up and extended his hand in greetings.

Ngugi was then minting money from big races.

His biggest pay cheque had come from the Bali 10km race in Indonesia where he missed winning his first cool one million dollars by one second but still walked away with $100,000 (Sh 12.95 million at today’s rates) in 1987.

He had recently opened the two-storey commercial building, Boston House and the wholesale shop, investments from his race earnings including from the 1992 Boston World Cross Country Championships.

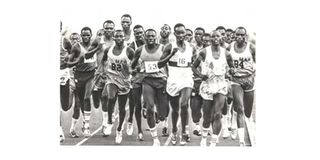

Retired Kenyan long distance runner John Ngugi leads Kenyan team in 5,000m race.

The man, John Whetton, an anti-doping official from the International Amateur Athletics Federation (IAAF), now World Athletics, wanted Ngugi's urine sample there and then as he reached into his carry-on bag and produced a small bottle.

Ngugi had to pass his urine while within sight of Whetton at the nearest rest room which he was to inspect first and ensure that there was no hidden bottle to minimise any risk of Ngugi exchanging the liquid with another person’s.

Unlike today, doping education was non-existent in Kenya and doping literally unheard of. Out of competition testing was also unheard of.

The only reported Kenyan case back then was of three times Boston Marathon champion (1993, 94, 95) Cosmas Ndeti who in 1988 was slapped with a three-month suspension for failing to report that he had a common cold and was using over the counter Cofta throat lozenge.

The IAAF treated this as a misdemeanour.

“He was adamant when I told him ‘no, you cannot come into my property and demand my urine in front of my wife and friends’. I had never given my urine to strangers," Ngugi, who lost nearly all his earthly possessions from the cost of litigation in Nairobi and London, recalled this week.

“It was like he was talking through his nostrils and we couldn’t understand what he was saying,” Ngugi said, adding that he was not well versed in the English language.

“It is then that I lost my cool and told Whetton that I was not a doper like white runners and invited him to come watch me run in the national cross country championships the following Saturday at Ngong Race course,” Ngugi recalled further.

“You will regret this,” Whetton warned Ngugi, returning the small bottle in the bag and walking away.

That brief exchange was to become a very costly mistake, said Ngugi who is a pale shadow of his former self -- a tall lanky youth with long looping strides that covered one and a half times the distance of an average athlete’s stride.

Ngugi travelled to Nairobi that Monday to join his team mate at Kibiku near Ngong town where the military team had pitched camp ahead of the national cross country championships.

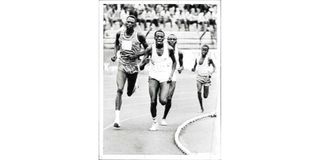

John Ngugi leads Moses Tanui at a past race.

On Saturday, February 18, 1993 before all the athletes proceeded for the roll call, Ngugi was told he would not run for failing to take a dope test.

He was then re-united with Whetton who shepherded him to the clubhouse toilet where he submitted his urine sample. He was told that he was not going to run for the next four years.

That evening, this writer sold the news to Agence-France Presse (AFP). The story spread around the world like bushfire.

The IAAF issued a statement from Monaco days later confirming Ngugi had been slapped with an automatic four years ban.

That terse statement brought down Ngugi’s sterling career that was peppered with five world cross country titles and the 1988 Seoul Olympic Games men’s 5,000m gold medal.

Ngugi proclaimed his innocence and chose to fight the ban. His agent, Briton John Bicourt filed an appeal case with the IAAF.

Ngugi travelled to the IAAF headquarters in Monaco for the hearing accompanied by a senior military official, Major John Karanja, who indicated that the KAAA never educated athletes on doping issues.

Ngugi says he spent $80,000 (Sh10.36 million) at today’s exchange rate) in 1993 but in the end, the IAAF upheld his sentence without appeal.

Concerned athletes led by Moses Tanui, the 1991 world 10000m champion, sent a petition to the IAAF to reconsider Ngugi’s case.

Meanwhile the KAAA remained aloof and unhelpful.

Two years later, on May 21, 1995, the IAAF's 23-member council, meeting in Gothenburg, voted unanimously to reinstate the then 33-year-old Ngugi.

That decision vindicated Ngugi and ended a 23-month campaign to clear the former cross country champion of any wrong doing.

The Council concluded Ngugi was not well informed about the procedure by Whetton minus any communication for the KAAA which did not have a doping programme and he had had difficulty understanding what Whetton was talking about in English.

After that, the world wanted to see the Ngugi of old competing again and his shoe sponsor Nike offered Sh5 million winning prize in the 1996 Stellenbosch World Cross Country Championships and an international marathon in South Africa to entice him back.

Ngugi, then a businessman in Kitengela, had ballooned to a 90kg giant.

He did try to get back to shape, shedding almost 30kg in three months to weight 62kg. But it came with a price as he says he aggravated a knee injury he had picked in 1987.

At the national trials, an out of sorts Ngugi finished 77, way, way out of the selection bracket marking the end of his running career.

But it showed his fighting character under tough odds

Ngugi’s story includes almost missing out being enlisted in the military in 1985 because he was perceived to be physically weak. One of the recruiting officers ordered Ngugi to take an extra daily ration of a packet of milk and a quarter kilogramme of meat to grow his strength.

“Within a month, I became stronger and ran so fast nobody could catch up with me. I once outsprinted a buffalo during early morning training in Ngong forest,” Ngugi says his eye lighting up.

Ngugi’s finest hour arrived in a very dramatic way on October 1, 1988 during the 5,000m final of the Seoul Olympics where he did the impossible by winning the race with a gap of 30 metres.

He became the first and only Kenyan to win the men’s 5,000m at the Olympic Games, 37 years ago, and counting.

The race spawned a book Train Hard, Win Easy, The Kenyans (John Ngugi) Way by Toby Tanser.

He says he will never forget his doping litigation that cost him his wholesale business, Boston House, transport trucks and personal vehicles.

Ngugi now lives a quiet live in Kitengela with his family.