Breaking News: Former Lugari MP Cyrus Jirongo dies in a road crash

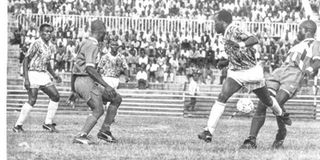

Deadly AFC Leopards striker Joe Masiga scores past Gor Mahia goalkeeper David Ochieng' inside a jam-packed Nyayo Stadium during the final of the 1984 Cecafa Club Championship on January 13, 1984.

Fans attending today’s Mashemeji derby have been promised lengthy bans and stiff fines for their clubs if they wreak mayhem on Nyayo National Stadium.

It is hard to pinpoint exactly when fans started destroying the shrines they patronize to cheer on their favourite teams. In days gone by, they just fought among themselves and left the place largely intact.

Unlike today, a football riot in the 1970s and early 1980s was a two-day event. It started the day preceding the big game. The protagonists supporting the arch-rivals, Gor Mahia and AFC Leopards, had a 50-50 share of the stadium which in those days was the Nairobi City Stadium. Leopards’ fans occupied the northern side of the stadium while their Gor Mahia counterparts took the southern one. Even the Main Stand where dignitaries sat was divided neatly into two halves for the blue and white cats and the green of the legendary medicine man.

Directly opposite the Main Stand were concrete terraces mysteriously called “Russia.” There were no sitting facilities on the rest of the colonial era playground, which were scornfully called “nyasi,” meaning grass.

Dan Ogad (second left) and Paul Ochieng (right) of Gor Mahia vie with John Odie (second right) of AFC Leopards as Kena Mukoya (left) and Tom Meja close in during their league match at Nyayo National Stadium in 1998.

They were the cheapest spaces, occupied by those who had sacrificed everything to afford a ticket but who were yet better off compared to the hopelessly devoted believers who couldn’t bring themselves to miss the game and so perched themselves on the bridge over the Mombasa railway line on Lusaka Road just to see a tiny fraction of the pitch.

The stadium was ringed with a stone wall that grew uglier with neglect each passing year. It had barbed wire on its rim but that didn’t stop some fans from scaling it. Some got their flesh torn for their pains. But the allure of the game brought them back again and again. Atop four pylons in a rectangle on each side of the football field were affixed a cluster of floodlamps that somehow did a good job at night, despite how they looked.

In the days when Kenya was ruled by an old man whose death people were prohibited from imagining or dreaming about lest by those acts alone they commit treason, two redoubtable figures were synonymous with this place.

One was Apollo Ndenda, whose title was simply Stadium Manager. A man of slight build with big, searching eyes behind horn-rimmed spectacles and a luxurious beard on his dark face, Ndenda was this gregarious, back-slapping jolly fellow who loved a good laugh. I never saw him dressed in anything other than a dark suit and tie, even on Saturday afternoons.

Ndenda was an old-school civil servant; he took his job of maintaining the stadium seriously and he did this with plenty of good cheer. I didn’t get to know where they had fetched him from or what his qualifications were but he was clearly a man in love with his job. He was obviously not availed much by way of resources and as the years passed, the stadium inexorably went to seed.

Today it is, of course, a horrible eyesore, both inside and outside. If somebody who last saw it in 1970 returned there, he could suffer a heart seizure.

The other man was a police chief named Henry Matalanga. He commanded Shauri Moyo Police Station, the destination of apprehended rioters. Matalanga was doubtless a professional policeman who was committed to keeping the peace. The trouble was his name. If he was leading his riot squad today, he would be disdainfully dismissed: “Your name betrays you!” There was never any way Matalanga was going to convince members of the Green Army that he was not “AFC damu” (“AFC Leopards by blood”) no matter what he did or did not do.

In point of fact, he probably was indeed AFC damu. But judgment preceded his actions. Oh, and by the way, Ndenda was “Gor damu.” Not that he uttered one word about it. It's just that his name betrayed him.

Matalanga’s duties started the day before match day. This was because, unlike today, the 12th man in a football team wielded inordinate power over the first eleven and the officials who managed them. He did this in a variety of ways including, but not limited to, placing charms on the opponents’ side of the stadium.

He blessed the players and cast spells on their opponents. He dictated all the dos and don’ts needed for a successful outcome and was well paid for his services although words like “witchdoctor services” were proscribed from clubs’ books of accounts. Officially, he didn’t exist but woe betide anybody who dared denounce him publicly.

To guard against the placement of debilitating charms on their territory, volunteers on both sides held vigil. That is when fights broke out. On the morning of the big match, there almost always were people Matalanga had locked up at Shauri Moyo Police Station.

Mashemeji is a Swahili word meaning in-laws. In many cultures, certainly in African ones, being in-laws is a relationship whose underpinning characteristics are politeness and mutual respect. Exactly why the fans of Gor Mahia and AFC Leopards settled on this word in reference to their acrimonious meetings, which often boil over into vicious fights, beats me.

The man who taught me journalism, the eternally-beloved Hilary Ng’weno, once himself a goalkeeper and whose brother, Archelaus Oundo played centre forward for the Uganda Cranes, stopped going to the City Stadium to watch football when he lost a shoe in a riot.

That was the story told to me by Philip Ochieng, the man who poached me from Hilary to join the Nation.

The inclement weather that saw heaven open did not stop fans from filling up Nyayo National Stadium for an epic football clash between Gor Mahia and AFC Leopards.

And once, when running helter-skelter amid a riot, I ran into Ochieng who was fleeing a cloud of teargas emanating from, of all places, outside the Main Stand. I didn’t know he had been at the stadium.

In the newsroom, Philip, a dapper dresser, was a commanding Chief Sub-Editor who hurled words like “Foolish!” and ordered scribes to “Arrive here!” to answer for their sloppy copy.

His loud voice used to override the ceaseless tapping of dozens of typewriters as he bellowed out his orders. But now here he looked so undignified as he ran for his life. Whoever said that a man in a hurry lacks dignity must have seen Philip Ochieng at the City Stadium. It is an image on my mind, decades after its occurrence.

One night there was a riot under the City Stadium floodlights. I was standing next to a car parked outside the Main Stand. I never saw the stone coming. All I heard was a shattering bang that momentarily stunned me. When I came to, the stone had dug a huge crater on the car bonnet, a foot or so from where I stood. Who had the strength to throw such a big stone to such an obviously great distance, I found myself asking over and over again afterwards. The thought that without my guardian angel, my head would have been on the way of that stone still makes me wince more than 40 years later. It was written for me that I would cheat that certain death.

Pele, of blessed memory, gave the football world the term “O jogo bonito” or “the beautiful game” in reference to football. But fans across the world, those of the Mashemeji derby among them, have made it anything but.

This is because they don’t know, or don’t care, about what the self-same Pele required of Brazil, the most successful football country in the world.

He said: “We have to be worthy and competent to show the world that we are not just five-times champions, but also people with feelings and manners, obeying the number one rule of every sport, and of life – to know how to lose.”

These words do not apply to Brazil alone. Whoever does not know how to lose does not deserve to win. And has no place among us. If indeed people have difficulty knowing how to lose, by all means lock them up for life and ban their clubs for many years.