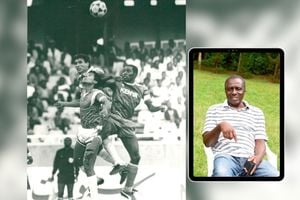

The then Gor Mahia captain Austin Oduor during a match at Nyayo Stadium in Nairobi.

If we rolled back the hands of time to those distant seasons of 1979, 1984 and 1987 where our football future lies buried with a bush over its tomb, we would find the eternal deputy, Makamu as they called him in Swahili.

We would find him first as a bright-eyed prodigy who has outgrown his football nursery school, Umeme Football Club, and seen his childhood companion and best friend, Sammy “Kempes” Owino help Gor Mahia to the final of the Cup Winners Cup and now, with his eyes on that horizon, believes he can win it.

Then we would experience the player revolt that made him Captain, enough of Makamu. And finally, we would be treated to that seemingly unrepeatable feat of him lifting the Nelson Mandela Africa Cup Winners Cup, his dream finally come true. There has been only one Austin Oduor and now he is dead. Long live Austin Oduor.

His generation brought us ball players - the freedom-loving, entertaining, exhibitionist types. Before him were the men of direct play, completely results-oriented. Both styles clashed, and badly so.

Football legend Austin Origi Oduor at a past match.

It was a clash that could only be resolved with the passing of one generation and the coming on of the next. And that’s what happened.

“Some of those guys,” he once told me, “Those - akina Laban, Obunga, Machine, Nyakota, they were not comfortable with us. They saw us as unserious kids who thought we knew too much.

But you needed to give them credit – they were great players and, in fact, we looked up to them. It was an honour to warm the bench waiting on them.” Laban Otieno, Andrew Obunga, Mike “Machine” Ogolla and Festus Nyakota are Gor Mahia greats of yore.

The boys of Ziwani loved possessing the ball. That’s why their defenders juggled it even inside the box in an era when penalty area play was strictly clearing and forwarding.

Austin took with him this mindset first to Luo Stars and then to Gor Mahia. It is a matter of debate why it was easy for this culture to take root in Gor Mahia and not other clubs which predominantly replenished their ranks from this same Lake region gene pool.

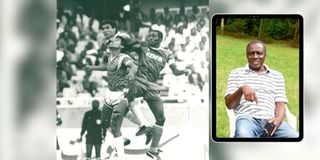

Football legend Austin Origi Oduor during a past event.

Teams such as Luo United, Luo Stars, Ramogi, even Kisumu Hot Stars, didn’t play “happy football” with the same naturalness that Gor Mahia did.

For Gor Mahia players, it wasn’t enough to win – it was mandatory to entertain the fans in the course of winning. Their fans were a spectacle, poets all. They told us: “In the first half, you will see Gor Mahia and in the second, you will see Mahia. Magic.” They were boisterous, dangerously depressed when defeated, but mostly infectiously happy.

The embodiment of this new culture, which took its inspiration from South America, was Austin’s childhood friend, “Kempes.”

Our beacon was always Brazil but in 1978, Argentina had won the World Cup with panache and gave the world a new superstar, Mario Kempes.

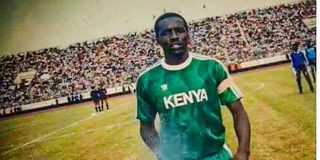

Gor Mahia fans promptly christened Kenya’s brightest youngster of the day, Sammy Owino “Kempes”. Austin played in defence and Owino attacking midfielder. Match reports of those days were effusive with the Owino’s defence-splitting skills.

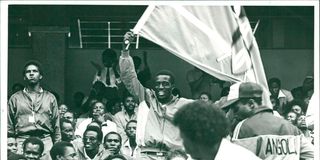

Football legend Austin Origi Oduor flies the Kenyan flag during a past match at Moi International Sports Centre, Kasarani.

They gave us licence for hyperbole, such as saying he touched every blade of grass on that City Stadium pitch. Our heroes then lived among us – we saw them, we touched them, we spoke to them, and we loved them. What a future we once had!

Owino, now running to become Football Kenya Federation President, remembers his Ziwani childhood thus: “Growing up, I had a close-knit group of friends who were like brothers to me. Austin Oduor, Chao, and Davie were my closest companions. We spent countless hours together, bound by our love for football and dreams of making it big.

Austin and I went way back—we were inseparable. I recommended him to Gor Mahia, knowing he had the potential to be great.

“My instincts were right. He went on to have an incredible career, culminating in his captaining Gor Mahia to their first and only African title, the 1987 Nelson Mandela Africa Cup Winners Cup. We were so close that we even roomed together for a while. Austin, Chao, and I were the serious ones—we didn’t smoke or drink and were focused on our goals. I have been in touch with Austin ever since. Our bond stood the test of time.”

Football legend Austin Origi Oduor during an interview at Makunga village in Kakamega county on April 16, 2023.

For the first 16 years of the team’s existence, Gor Mahia officials selected the team captain. It is during the later years of this time that Austin famously became the perennial deputy, Makamu. And then Zamalek happened.

In 1984, the team lost its cool when playing Egypt’s Zamalek in Cairo in a Champions League match and set upon the referee. (Austin disputed this version of events, saying the referee play-acted.) Be that as it may, the club picked up a two-year CAF ban. Coach Len Julians and six players also received suspensions.

As the club moved to repair its decimated ranks, the players categorically told their officials that from then henceforth, they would be selecting their captain and officials were to keep away from that exercise altogether. It wasn’t a request. “I didn’t ask anybody for the position,” Austin would later tell me. “I just sat back. But my colleagues came to me and said, ‘you are now the captain.’ I accepted.” They kept him there until he hung his boots.

I have interacted with Austin on and off since Gor Mahia’s epic victory 1-0 over Simba of Tanzania in the 1981 Cecafa Club Cup in Nairobi.

He was one of the most incisive contributors to a workshop I ran in 1994 under the auspices of Team Players on how former players in conjunction with the then Kenya Football Federation could leverage their experience to develop football in Kenya’s schools. And in 2018, he was one of the guests who graced the launch of my book Kick-Off: The Game, The Glory and the Greats of Kenyan Football. He is, doubtless, one of the Greats.

The most shocking interview he gave me was the fraud done on Gor Mahia players after their peerless win in 1987. I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. I had thought all along that they had been handsomely rewarded. In fact, the opposite happened.

Officials gave the players false hope that if they reached the semi-finals of the tournament, each would get a plot in the Kasarani area of Nairobi. “I cannot tell you just how energised we became as a result of this promise,” he told me.

“We all saw economic security beckoning. Playing football was going to be worth all the rigour. After we defeated El Mereikh, the officials informed us that the task force set up for that purpose had collected enough money to buy us the plots. We were ecstatic. However, we kept focus on the Cup.”

The players did one better than the semis – they won gold on Kenya football’s most memorable day, December 5, 1987.

“It was an indescribable moment for me,” Austin recalled for me in a story I wrote for Nation.Africa Sport about the broken promise of 1987. “After the lap of honour, the team retreated to camp at the Kasarani Stadium’s hostels.

After we’d settled down, the first thing I expected was our officials coming to offer their congratulations and to tell us the way forward. But you know what? None was there! We shortly learnt that they had driven into posh clubs in the city to celebrate. As captain, it fell upon me to know what to do with the team. All this time, I either held onto the trophy or kept a very keen eye on whoever asked to hold it.

“After dinner, I approached the hostel’s management and requested them to give us two crates of beer and two crates of soda so that we could celebrate. I myself didn’t drink – and still don’t - but many players did and I had to do something for them. Soon, restlessness, occasioned by lack of official direction, set in. The camp broke up unofficially.”

The following day, team officials visited the camp. Without ceremony, Amos Nandi, the team manager, distributed the players’ allowances.

These added up to about Sh2,100 per player calculated at Sh150 per day for 14 days in camp. It is money that was owed to them and would have been paid anyway whether they’d won or lost. Then the officials left. There was no mention of the plots – not then, not ever again.

A sensitive man with a strong ethical backbone, Austin told me this story with visible hurt, the two-decade long passage of time notwithstanding. He spoke of those teammates who had died and wore a hauntingly sad smile as he remembered them. With hope of that promise being kept gone for good, he called the aftermath of the 1987 win the disappointment that lasts a lifetime.

As for Gor Mahia, which remains homeless despite 56 years of existence, all it can do is win a nondescript premier league over and over with a guarantee that it will be overrun at the preliminary stage of the African competition by a team from whichever direction of the compass. Why do they bother? Gone 1979, gone 1987.

Austin told me he didn’t prize December 5, 1987 the way he prized December 10, five days later. December 10 is when his daughter, Pauline Oduor, was born.

May she and the rest of the family find comfort in the knowledge that their father used his time in this world well. He spread joy beyond his family. He was let down by unworthy men. But his memory will outlast them all.

Someday, somebody who values his contribution will take charge of Football Kenya Federation. And then Austin Oduor, our unforgettable captain, will be redeemed. Until then, may Austin’s celestial days be filled with peace and light.