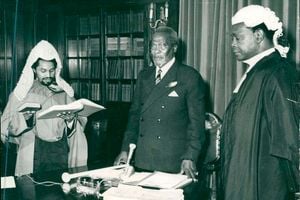

Former President Mzee Jomo Kenyatta.

By late 60s, it had already dawned on western powers that Mzee Jomo Kenyatta’s grip on power was short-lived due to his old age and health issues. This triggered a flurry of discussions and disagreements in the corridors of power in White Hall, London, and the US State Department in Washington in their efforts to influence the succession.

While America’s suggestion to the British was that Kenyatta should be persuaded to resign before it was too late, British diplomats vowed not to support such a plot which they felt was ill-advised, hitherto restricted papers reveal. Instead, they wanted a successor who would be groomed in readiness for the eventual departure of Kenyatta from the political scene.

Because of Kenyatta’s prominent role in protecting their interest coupled with Kenya’s strategic importance, the west was becoming worried about the future without Kenyatta and the question among them became ‘Who after Kenyatta?’ “The removal of Kenyatta’s control over the Kenya government poses dangers to the British and the western position,” noted one official from the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in a very confidential paper titled ‘Question on the succession to President Kenyatta’.

Determined to influence the succession, Washington and London looked at different scenarios which could necessitate the transfer of power. One was when Kenyatta ceased to be president suddenly due to death, illness assassination or abrupt resignation. Second was that Kenyatta’s continued stay in power could result in power slipping away from him into the hands of untrustworthy politicians around him. These were scenarios the west wanted to avoid at all cost by propping up a successor who would take care of their interests at the same time be acceptable to Kenyans.

The Acting Director for East Africa at the US State Department John Meagher, while agreeing with his British counterparts that the question of succession in Kenya should be taken seriously, suggested that Kenyatta be influenced to resign and hand over power to a pro-west successor. Meagher understanding how difficult such a task would be, proposed for an influential figure such as Sir Malcolm MacDonald to persuade Kenyatta into resignation.

American diplomat

One of those the American diplomat thought of as possible replacements for Kenyatta was Tom Mboya, whom he described as “the man to watch” and the most intelligent among the possible successors. However, he thought Mboya stood very little chance because of his tribal background. In this regard, he proposed a couple of Kikuyu politicians he believed stood a better chance based on the tribal nature of Kenyan politics. In his views Attorney General Charles Njonjo and Kenyatta’s nephew and Cabinet minister Njoroge Mungai stood better chances. He also thought highly of Mwai Kibaki but not as a serious contender.

The Americans’ suggestions, especially on the question of Kenyatta’s resignation, were strongly dismissed by the British, who even started contemplating whether they should continue engaging with the US State Department in Washington over the matter. They felt that the East African Desk at the US State Department led by Meagher, who was in an acting capacity following the transfer of Curtis Strong, was clueless and blind to the real political situation in Kenya.

The British argued that unless a substantive official who understood the situation in Kenya was appointed as the head of East African desk at the State Department, they were better off engaging with officials at the US Embassy in Nairobi who understood the political situation in Kenya.

“Until we know how Curtis Strong’s successor in the State Department sizes up the position, it would be better to avoid becoming too involved with the Americans in Washington in a detailed examination of the Kenyan position,” wrote an official from Number 10 Downing Street, the official residence and office of the British Prime Minister. The British diplomats resolved to use future consultation with the Americans to distance themselves from any plan to have Kenyatta resign, and to counter their “misinformed” views on the political situation in Kenya. They felt that the lack of clear understanding of the political situation in Kenya by the Americans was because they relied too much on information given to them by Tom Mboya.

Constitution

“I believe that the objective of each consultation should be to head the Americans off from the notion that we should intervene actively to invite Kenyatta to step down and secondly to broaden their outlook and counter their tendency sometimes to see the Kenyan situation through Mboya’s eyes,” the then-British High Commissioner to Kenya, Sir Edward Peck, advised London.

On Mboya as a possible successor as suggested by the Americans, the High Commissioner advised his seniors in London that Britain should stay away from Mboya and be very careful in dealing with him because of his strong American connections which were resented. “I should add that we must also be very cautious about Mboya’s relations with the Americans,” he wrote. “Kanu and KPU alike inside the National Assembly and out give constant vent to their obsessions about CIA activities in Kenya and their preference for the British way of life to the Americans.

He continued: “The United States Embassy here has complained to us of the increased frigidity which they have encountered in officials and ministers during recent months. In these circumstances it is natural for them to concentrate their frustrated patronage on Tom Mboya; the one man who is generally prepared to give the United States a pat on the back in public speeches and to confide in Americans in private.” On America’s suggestion of Mungai and Njonjo as possible successors, they thought the latter stood no chance as a long-term candidate because he was aloof, detached from the common man and ruthless in dealing with the opposition. Although they agreed that Mungai was well liked by the Kikuyu haves and was intelligent, he was lazy and a political lightweight compared to Oginga Odinga’s ally Bildad Kaggia who was much liked by the Kikuyu have-nots.

Charm and charisma

One politician who never featured as a possible successor in those early discussions between Washington and London was vice president Daniel Arap who later succeeded Kenyatta. Despite occupying the second office in the land, he was less and less mentioned as even a compromise successor to Kenyatta. Perhaps this was because unlike Mungai, Njonjo and Mboya he had no close associations with either of the two countries and lacked the charm and charisma of the three.

A senior diplomat in Nairobi advised London, “President Kenyatta respects him (Moi) as an honest man as undoubtedly he is. But we know from our own observations as well from the authoritative word of expatriate advisers who have seen him acting as chairman of various committees that he is mentally very slow and at some time prone to intractable stubbornness.” The diplomat also revealed to his seniors that as Minister for Home Affairs, Moi had played a role in the deportation of Europeans in July 1967. “You will also have seen our reports suggesting that Moi was similarly ham-handed over the European deportations in July,” he wrote. In other words to the west, Moi was completely a non-factor in the succession race. However these changed following the constitutional amendments of 1968, which stipulated that in case of the president’s death the vice-president would take over as president for 90 days after which an election would be called to elect a substantive president. The constitutional changes effectively put Moi firmly on the succession saddle.

By 1972, officials at the East African Department at the Foreign and Commonwealth had accepted this reality and changed tune. “As you know, we have thought that a hopeful prospect for the succession was a takeover by Moi with Mungai as his right-hand man. Some may think such an arrangement is unlikely to last long but its existence as a possibility has been a stabilising force,” wrote SY Dawbarn of the East African Department at the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in a letter copied to the British Cabinet Office. Moi, who was viewed as a non-starter in the succession race, ascended to power in 1978 following the death of Kenyatta and ruled for 24 years.