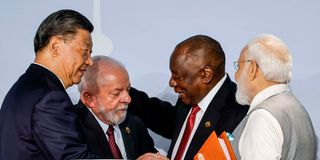

From left Presidents: William Ruto (Kenya), Xi Jinping (China), Cyril Ramaphosa (South Africa), Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva (Brazil), India's Prime Minister Narendra Modi and President Vladimir Putin of Russia.

| FileWeekly Review

Premium

Building Brics: Kenya and the new world order

President William Ruto has been on the warpath against the dollar and spearheading the “de-dollarisation of African economies”. For that, he has already won accolades, and applause, from the Brics nations – Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa – which have been calling for the same. The Americans want President Ruto on their side – which explains the recent pronunciation by the US ambassador, Meg Whitman, on the fairness of his presidential victory and the need to strengthen the US-Kenya trade partnership. Last month, top Chinese diplomat Wang Yi was at State House, Nairobi, where he had discussions with the President before the Brics meeting in Johannesburg.

But the push for establishing an alternative Brics currency to rival the US dollar as the global reserve standard has been of interest. Russia – now making inroads into Africa with its fertiliser diplomacy – has been making calls for the replacement of the dollar as the world’s reserve currency for years. Other proposals were for a modest return to the gold standard in the basket of five currencies that make up the Special Drawing Rights of the International Monetary Fund. On the other hand, China has been looking forward to internationalising its Yuan currency, and several central banks now include it in their reserves.

While the debate on ditching the dollar has been with us for years, it has recently been fueled by the weaponisation of the dollar – which has become a tool of aggression against countries that go against the US hegemony. The latest victim of such a sanction is Russia, whose banks have been removed from the SWIFT international payments system as punishment for invading Ukraine.

Central African Republic President Faustin Archange Touadera (left), Republic of Congo's President Denis Sassou Nguesso (left), Filipe Nyusi of Mozambique (right) and Equatorial Guinean President Teodoro Obiang (right) attend a meeting during the 2023 BRICS Summit at the Sandton Convention Centre in Johannesburg on August 24, 2023.

With the shilling under pressure from the dollar, Kenya is not one of the nations spoilt for choice. Rather, it is caught between the devil and the deep blue sea. How far President Ruto will influence the anti-dollar revolt remains to be seen. He has, however, been posing questions in international forums, hitherto murmured by African nations. In his first challenge to African leaders, President Ruto asked why they should be looking for dollars to trade with each other. While addressing the Djibouti Parliament, President Ruto posed: “From Djibouti selling to Kenya or traders from Kenya selling to Djibouti, we have to look for US dollars… How is the US dollar part of the trade between Djibouti and Kenya? Why?”

The same observation was posed by Cabinet Secretary Alfred Mutua while addressing the Brics Summit: “Today, listening to the discussions here and remembering the way we traded, and the current system which is pegged against most of us, I tell myself that the issues are no longer about if but when we will adopt a fairer, predictable and reasonable way of transacting with each other.

“My ancestors would be shocked, for example, if they woke up today and found that Kenyans cannot use the shilling to buy goods in Tanzania, without using an external currency, resulting in high foreign exchange interests. Quite ridiculous, to say the least.”

African political union

Kenya’s position takes a cue from previous leaders who asked African nations to establish a single currency. The last push was by Libya’s Colonel Muammar Gaddafi, who made a gallant effort to create a single African currency based on gold deposits.

The first such campaign was by Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah, who advocated for an African political union with a standard defence policy, common currency and one citizenship.

During the Brics summit, calls for changes to the World Bank and International Monetary Fund were made. Dr Ruto has similarly been arguing that the IMF and World Bank are hostages to rich nations. But this created a recent debate with Prof Steve Hanke, an economist at John Hopkins University, retorting: “(President Ruto) got it wrong. Poor nations who become heavily indebted to the IMF become ‘hostages’.”

In 2014, and to show its resoluteness, Brics formed the New Development Bank as a multilateral development bank with seed money of $50 billion. In its strategy paper, the NDB says financing in local currency will account for a “substantial share” of NDB operations. “Local currency financing is a key component of NDB’s value proposition, as it mitigates risks faced by borrowers and supports the deepening of capital markets of member countries,” says the paper.

Chinese President Xi Jinping, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov pose for a group photo during the 15th BRICS Summit in Johannesburg, South Africa, Aug. 23, 2023. The 15th BRICS Summit was held in Johannesburg on Wednesday.

With recent financial reports indicating that Brics is already the world’s most extensive gross domestic product (GDP) bloc in the world and that it is contributing 31.5 per cent to the global GDP, ahead of the G7, which contributes 30.7 per cent – it will be hard to write it off in its war against the dollar hegemony.

The dollar bulldozed its supremacy after World War II and was pegged to the gold standard at first while other world currencies were pegged to the dollar. Then in 1971, the US pegged its dollar’s value to a floating exchange rate in relation to world currencies. For the last 75 years, the dollar has emerged as a dominant currency in international finance and trade. The problem has been that any shocks to the dollar spill to all other countries. This is part of the conversation that has been taking with the resurgence of the de-dollarisation of the economies.

Read: The new Gaddafi? Ruto’s bold statements on de-dollarisation and a united Africa attract attention

There are pessimists in Western circles, too, on Brics’ success. The Washington Post columnist Ishaan Tharoor predicted that BRIC’s annual summit “may be another talk shop” and argued that the bloc has “muddled along for the past decade”. What was more? Its constituent economies have performed unevenly, and its member states have locked horns. “The bloc’s only tangible accomplishment was the launching of an international development finance arm, headquartered in Shanghai,” said Tharoor.

In July, India signed an agreement with the UAE to settle bilateral trade in rupees instead of dollars, thus eliminating dollar conversion costs. Whether Kenya will go this route is yet to be seen. The South African Finance Minister Enoch Godongwana has already said that his country is still being prepared to enter the de-dollarisation discourse since its economy is skewed towards the United States and the European Union.

Some critics argue that the de-dollarisation campaign is a Chinese agenda to expand the geography of its RMB currency and especially in Brics’ commercial exchanges – a move that would ultimately change the international monetary system.

The escape from the dollar hegemony has fueled the talk, especially for indebted countries such as Kenya. Early in the year, Nairobi proposed paying for its fuel exports in Kenyan shillings to combat the dollar shortage. But the credit agreement signed with UAE’s ADNOC and Saudi Aramco was for the supply of petroleum products with a six-month credit period described by industry analysts as a postponement of demand.

Strengthened the shilling

However, it highlighted the dollar crisis that faced the country for a short period of settlements, an issue that was putting the shilling under pressure due to the shortage of dollars. The move has not strengthened the shilling against the dollar, and it hit an all-time low after breaching the Sh150 threshold for the first time. More so, for the last 50 months, the shilling has lost 50 per cent of its value. This has partly been attributed to interest rate adjustments in advanced economies.

If Kenya enters Brics – and the de-dollarisation turns to reality – experts argue that members would “achieve a level of self-sufficiency in international trade that has eluded the world’s other currency unions”. That is according to Joseph W. Sullivan, a senior advisor at the Lindsey Group and a former special advisor and staff economist at the White House Council of Economic Advisers during the Trump administration.

(From left to right: President of China Xi Jinping, President of Brazil Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa and Prime Minister of India Narendra Modi gesture during the 2023 BRICS Summit at the Sandton Convention Centre in Johannesburg on August 24, 2023.

In a recent article in the Foreign Policy journal, Sullivan argued that “the Bric (currency) would not so much snatch the crown off the dollar’s head as shrink the size of the territory in its domain. Even if the Brics de-dollarised, much of the world would still use dollars, and the global monetary order would become more multipolar than unipolar”.

Others argue that the bullying tendency in the US would be put under check. Recently, South Africa and the US had a diplomatic row over Pretoria’s close ties with Moscow. South Africa’s Cyril Ramaphosa alluded to this by reminding Washington that “during the Cold War, the stability and sovereignty of many African countries was undermined because of their alignment with the major power”.

According to President Ramaphosa, this forces countries to “seek strategic partnerships with other countries rather than be dominated by any other country”. Whether President Ruto will push for Kenya to join Brics – or whether he might fall to the praises emanating from Washington remains to be seen. Will Kenya pick the hot Brics?

[email protected] @johnkamau1