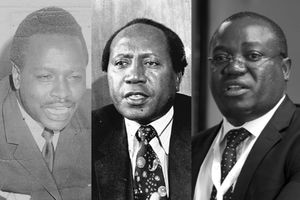

JM Kariuki.

The British always thought they had contacts within the Jomo Kenyatta state. But when JM Kariuki disappeared on March 2, 1975, some 49 years ago, they realised that they had limited contacts. It was a shock.

Historians who have studied that period’s diplomatic papers and notes agree that until then, the British thought they understood Kenyan politics and politicians. They didn’t.

“They had believed that they understood Kenyan politics and politicians, and this was challenged (after Kariuki’s death) – as either their Kenyan contacts were lying to them or they, too, were not in complete control when Kariuki went missing,” argues Dr Poppy Cullen in her book, Britain and Kenya after Independence. She said: “The knowledge of British diplomats was always dependent upon what they were told, and now their interlocutors kept them misinformed.”

At first, on learning that the populist politician had disappeared, the British diplomats had relied on these government contacts only to realise they were duped. In their first report on JM, they said: “Kenyan authorities assured us that they know nothing. Neither we nor the Americans have any information so far to contradict this.”

But as contradictory statements on JM’s whereabouts started to emerge, two of their contacts, Starehe MP Charles Rubia and Bahati’s Dr James Muriuki, had an unofficial meeting with Christopher Hart of the British High Commission. In his report to London about that secret meeting, Hart sought silence on Rubia’s visit. He said Rubia was “very nervous about being overheard and checked on the reliability of our servants first”. While seeking this silence, the High Commission official said it was “vitally important that our various links with the present regime do not enable the Kenyans to discover anything of Rubia’s visit”. Since he knew Hart personally, Rubia had decided to contact the junior official (rather than the High Commissioner). “He also knows me socially and had been to the house recently,” wrote Hart.

Since independence, Britain had relied on an elite circle around Attorney-General Charles Njonjo and Cabinet minister Bruce McKenzie – who became the most reliable figures in structuring the Anglo-Kenyan relations. Some historians, such as Dr Poppy Cullen, have recently found evidence that JM was seeking to be included in this circle of Njonjo and McKenzie. In the British files, the ex-Mau Mau detainee was described, at least in 1964, as “unpleasantly anti-white, although perhaps not strongly pro-communist”.

Economic frustrations

JM was a capitalist – like most of the elite in the Kenyatta circles – only that he advocated for a welfare state. He also used the economic frustrations that faced the landless to build a powerbase – almost similar to Dr William Ruto’s “Hustler” narrative. JM may have been populist – and critical of Kenya’s land redistribution and settlement. That could explain why he was unpopular in British circles, who spoke negatively about him. In 1973, Anthony Duff, the British High Commissioner to Kenya, and later head of MI5, described JM as a “rogue politician, a professional enfant terrible of boundless energy, muddled ideas but formidable charisma”.

It appears that JM knew that the British disliked him and sought to repair the damage. As one of his aides told a High Commission official in September 1970, “Kariuki feels that the High Commission is unfriendly towards him and is deliberately ignoring him. Je wished however to make it clear that he is not unfriendly towards Britain or against British business interests (despite his speeches) and that he would like to see more of the High Commission”.

In the same year, at the East African Division, some officials including Robert Purcell thought that it was worth cultivating relations with Kariuki despite his radical views. The British were possibly looking for a post-Kenyatta generation that would serve their interests.

Kariuki’s assassination in 1975 appear to have caught the British unawares and as Dr Cullen argues in her book, “the murder showed that they were not as knowledgeable as they thought, and that they were less in touch with events and individuals they had believed”. They would also tend to exaggerate the political outcomes. For instance, when JM disappeared, Rubia told a High Commission official that if JM was killed, Kenyatta would also be killed by an “outraged populace”. The outrage was limited and did not shake the Kenyatta state.

While Rubia was right that the government had deliberately misinformed the country, the former Nairobi mayor was off the track on Kenyatta being killed. On JM, not only were Kenyans duped, but also the diplomatic community. Besides relying on their official intelligence, the British diplomats also relied upon what Kenyans told them. The diplomats were, thus, surprised after Kariuki went missing, and they realised that their contacts were also misinformed.

While Rubia thought that JM’s death also marked Kenyatta’s end, the British High Commissioner, Anthony Duff, knew that it was not easy to replace Kenyatta. He suggested that going forward, they should “encourage” the Kenya government to “take things gradually out of the president’s hands”. Since Britain could do little in the JM aftermath and still wanted to retain relations with Kenyatta’s government, they became the focus of attacks by radical MPs. As Duff wrote, “We are regarded by the critics as a sinister eminence grise and by sine members of the establishment as a kind of scaffolding that keeps the building intact”.

The two previous envoys before Duff had anticipated that Kenyatta would die during their tenure. They had even worked on the State burial modalities with some Kenyan officials in a scheme hatched by Bruce McKenzie. After Kariuki’s death, Duff wrote another despatch in August 1975 at the end of his tenure: “I do not know whether my predecessors were disappointed that they left the country with Kenyatta still in the saddle. I am, not because I crave excitement, but because I believe it is bad for Kenya that he has lingered so long.” But at the East African Division they knew that Kenyatta and Kenya were symbiotic twins. “Kenyatta has been Kenya, Kenya has been Kenyatta,” wrote Desmond Wigan in a September 1975 note.

Political hangers-on

It was Kenyatta who was left to handle the JM mess created by some of his security officers and political hangers-on. That he was alleged to have expunged the name of Mbiyu Koinange from the report of the select committee that investigated Kariuki’s assassination – and that the senior officials mentioned in the report were never investigated was either a pointer to the weakness of the presidency or a combination of State capture.

Some 49 years after Kariuki’s assassination, various schools of thought have emerged on the motive behind his killing. What tops the chart, and the political discourse is the Kenyatta succession in which JM was claimed to be ahead of the Kiambu mafia.

But talk of business deals with security men gone wrong and matters of the heart have also been floated. What has never been answered is why the State was reluctant to arrest those mentioned. But for the British, it was a time to reflect on how they collected their intelligence within Kenya. May JM continue resting in peace.