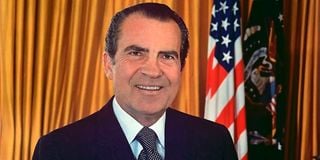

Richard Nixon, the 37th President of the United States of America (1969-1974).

The Republicans have returned to the White House, ushered in by Donald Trump’s triumph, and it’s a fitting moment to delve into the archives and examine the impressions left by the first two Republican envoys to Kenya. Just six months after President Richard Nixon, the Republican candidate, took office in January 1969, Kenya was teetering on a knife’s edge.

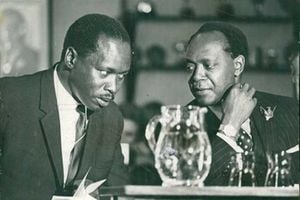

The assassination of Tom Mboya in July that year marked a seismic shift, and Jomo Kenyatta responded with an iron grip, launching a sweeping crackdown on the opposition Kenya People’s Union (KPU), led by Oginga Odinga which was capitalising on the murder.

By the time Nixon won his seat, the politicians in Nairobi had lost interest in US envoys. First, the Americans had already run afoul with the Jomo Kenyatta government over their first ambassador William Atwood book, The Reds and the Blacks, which had quoted conversations with senior political leaders which they thought was off-the-cuff. The damage caused by Atwood reverberated for some years.

Rather than send a political appointee, Nixon decided to go for a career diplomat, Robinson McIlvaine in 1969. “There was some concern about Jomo Kenyatta, who was of a certain age and Tom Mboya, the obvious successor to Kenyatta, had been assassinated,” McIlvaine had later recalled on his appointment. Had Mboya not been assassinated, McIlvaine argued, “I think, frankly, another non-career would have gone there ... Maybe they decided there might be a coup d’etat, and you’d better have old anti-insurgency McIlvaine there.”

Arduous task

McIlvaine revealed something else in the1988 interview: That Atwood lost some land he had bought in Kenya, and that he had hoped to one day settle in the country.

“He was never able to go back and hasn’t to this day,” said McIlvaine in 1988. “The old man —that’s Kenyatta—was very annoyed, as was the attorney general, Charles Njonjo, because he was the one that was quoted as saying nasty things about other people still around. The word went out that nobody in the government was to have anything to do with Embassies, except the foreign minister.”

As the Americans found out after Atwood, getting Kenyatta became an arduous task: “My main contact was with Moi, who was the vice president. I found that I could get to see him relatively easily. He was very serious, no great intellect, but he was a hard worker. He was a very loyal vice president to Kenyatta and probably couldn’t have had the job if he hadn’t done it that way.”

And that tells us about the choice of diplomats — now that there might be a reshuffle at the Embassy in Nairobi as pressure on Meg Whiteman’s departure starts. Kenya has always been of interest to the US and the diplomats have never hidden this fact.

“We had an interest in the stability of Kenya and in Kenyatta, and in what happened after his death. Everybody who ever came there would always ask me, ‘Has Kenyatta named a successor?’ I would explain that people don’t do that,” recalled McIlvaine who stayed in Nairobi until 1974. The next Republican appointed was Anthony D. Marshall who was named envoy in the fading months of Nixon’s presidency as the Watergate scandal closed in.

“I hope you don’t get run out,” Nixon remarked during the noon meeting, January 14, 1974, as he met Marshall at the Oval Office. “Most of these African countries are disaster areas.”

Marshall was not a stranger to diplomatic drama. In 1971, he was kicked out of Madagascar after President Tsiranana’s regime declared him persona non grata on charges of interference with the country’s internal affairs. Tsiranana had accused some of Madagascar’s ministers of visiting an unnamed embassy to conspire him. Thus, Nixon did not want Marshall, a former CIA agent, to get into trouble with Kenyan officials.

“Now Tony, don’t get kicked out of any more countries,” said Nixon.

Marshall had already been briefed by Attwood’s successor, Glen Ferguson, that running an embassy in Kenya “was like operating in an iron curtain country.” He also told him that Kenyans simply didn’t want anything to do with the American ambassador. As Marshall later remarked, “(Atwood) wasn’t entirely forgotten by the time I got there, but what I was pressing was not politics, I was pressing business. And they were interested in business. And there was an opportunity for business in Kenya.”

Marshall, a shadowed figure of the CIA, embarked on a self-financed mission in 1954, during the tumultuous Mau Mau years. His journey cut through East Africa, tracing a path from Kenya to Tanganyika, across the wilds of Somalia, and then to Uganda. In Kenya, he found himself face-to-face with General Sir George Erskine, the commander of the British East Africa Forces, exchanging words over the undercurrents of colonial unrest. His stay was graced by none other than Sir Philip Mitchell, the former Governor, whose memory of imperial rule was always impeccable.

Period of stability

During the White House meeting, Nixon’s thoughts on Kenya were captured in the declassified Memorandum of Conversation. Nixon knew that not all diplomats loved to be sent into such a crucible. “I’m glad you want to go back. Most want to stay away,” he told Marshall, who had previously served in Madagascar from 1969 to 1971.

Marshall replied, “Madagascar wasn’t truly Africa. The people are more Polynesian — and drifting toward China. I’m really going to Africa for the first time. Madagascar is rushing to outpace others. Kenya has a much better chance. I want to work with them.”

Then Nixon added: “They have had a period of stability with a strong leader. He is good and strong.”

Though he never mentioned President Jomo Kenyatta by name, whatever Nixon was calling a period of stability was the enforced silence on the opposition leaders, led by Oginga Odinga, and the continued ban on Kenya People’s Union.

Nixon’s monologue was on Kenya’s strategic importance. “That part of the world is important for the future,” he remarked. One would presume that there was a hint of resolve in his tone.

“We must let them know Kenya is top priority—without giving the impression to others that this is the case.” In Nixon’s eyes, Kenya was a linchpin in the global chessboard, a nation worthy of attention but one that required careful handling, shielded by the quiet diplomacy that Nixon valued.

In the context of Cold War, Nixon’s perception — and that of the Republicans — was that Africa deserved “strong leaders”, nay dictators, or a strong central authority to keep Soviet Union at bay. He warned Marshall of the underlying elite struggles in Kenya, and perhaps, his fears: “They will start gobbling up each other. But we are building for the future — they must think we are building for the present. Do you agree?” He asked Marshall.

“I certainly do. Kenya is one of five or so which have the best chance. We should build on them,” said Marshall.

By then, the Americans did not believe so much on African democracy. They wanted to cultivate strong leaders. Several years later, in an interview with Library of Congress, Marshall would revisit this issue of whether Kenya ought to have a democracy, at that moment.

He said: “I am not as solidly sold as some people, including President Nixon, that all the world should have democracy. I don’t think that developing countries can jump right into being a democracy. I think they have to go through some painful steps first. I think that one of the processes that can take them more quickly and better through painful steps is a benevolent dictator. I think that Kenyatta was a benevolent dictator.”

What we later know is that Kenyatta tried to get as much as he could from the US, especially on the expansion of the military in order to tame the expansionists in Uganda and Somalia.

But of importance is that the conversation and tour of duty between Marshall and McIlvaine is interesting in that it reveals the realities of the 60s and 70s and how diplomats viewed Kenyatta’s Kenya. It also shows that one diplomat can wreck hell, the way Atwood did.

@Johnkamau1