The late Jaramogi Oginga Odinga. Commonly known as the doyen of Kenyan opposition politics.

Following the advent of multipartysm in the early ‘90s, most people seemed to agree that for the first time the stars appeared aligned for Jaramogi Oginga Odinga in his long quest for the leadership of Kenya.

The unpopularity of President Daniel arap Moi’s regime and the end of the Cold War created a perfect moment for him just as he entered his sunset years.

With the fall of the Soviet Union, communism was no longer considered a threat, and people like Jaramogi who had been unfairly labelled as communist could now be understood without the biases of the East-West struggle.

The west, which had kept him at arm’s length, started being receptive towards him, viewing him as one of the progressive leaders who could play a great role in getting rid of the corrupt and oppressive Kanu regime.

At the end of October 1992, when Jaramogi made a snap visit to London in the company of James Orengo, the British hurriedly secured an appointment for him. The 1992 elections were just approaching and there were rumours within the opposition ranks that Britain was planning to assist Moi to rig the elections.

Neither the Foreign Office nor the British High Commissioner to Kenya, Sir Walter Kieran Prendergast, knew about Odinga’s visit until very late.

Jaramogi Oginga Odinga (left), his wife Mary and their son Oburu Oginga at their Kileleshwa home in Nairobi.

In fact, the East African Department in the Foreign Office only came to know about his presence in London after Lord David Steel, the former leader of the Liberal Democratic Party, made a call requesting the department to help the Ford-Kenya leader secure an appointment with the Minister for Overseas Development, Lady Chalker.

Sir Prendergast, who only came to learn about Jaramogi’s visit to London through the front page of the Nation, wrote a complaint to the Foreign Office: “Oginga Odinga’s visit to London last week brought us up against a perennial problem about Kenyan politicians. Most of them have extensive contacts there, and think it is nothing out of the ordinary to hop over for a few days. We continually urge them to get in touch so that we can help to arrange calls on British ministers but, particularly in the heat of the election campaign, they do not always remember. Odinga’s visit is a case in point: The first we knew about it was the front page of the Nation the day after which included among other things an allegation that we had secretly delivered 40,000 ballot boxes.”

T.G Hariss of the Foreign Office agreed with Prendergast, writing: “I understand your frustration at the lack of any prior warning. I do not really think the department could be faulted on this occasion. The problem, as you say, lies with opposition Kenyan politicians who simply turn up in London unannounced and expect to be received at ministerial level with no prior notice.”

Nevertheless, once the Foreign Office became aware of Jaramogi’s visit, its officials from the East African Department were determined to have him meet a senior official to eliminate any suspicion.

In the absence of Lady Chalker, officials rushed around and finally arranged for Jaramogi to call on Mark Lennox Boyd, the Parliamentary Under Secretary of State in the Foreign Office. During the meeting, Mark Lennox Boyd assured Jaramogi that Britain would remain impartial in the Kenyan election and dismissed the rumours about interference.

Boyd was the son of British Colonial Secretary Alan Lennox Boyd, who had imposed a constitution on Kenya in 1957, triggering strong opposition from the nationalists among them Jaramogi, Tom Mboya, Masinde Muliro, Moi, and Jeremiah Nyagah. Odinga, therefore, really relished meeting his son.

“During their brief conversation, Boyd, at our request, urged Odinga and Orengo to maintain close contact with your High Commission and stressed the importance of letting you know in advance the next time he visited the UK so that proper arrangements could be made,” the East African Department informed the High Commissioner in Nairobi.

KPU leader Jaramogi Oginga Odinga (with cap) in an exchange with President Jomo Kenyatta in October 25, 1969, shortly before Mzee's bodyguards opened fire and killed about 50 people in Kisumu.

As rushed as the meeting was, it showed Odinga’s changing fortune with the West who all along viewed him as the biggest threat to their interests. This emanated from their tendency of labelling anyone who visited Eastern capitals, especially Moscow, as a communist.

They had vetoed his inclusion in the 1962 coalition government when Kenyatta proposed his name as Minister for Finance, removed his control over the police when he was appointed Home Affairs Minister on June 1, 1963, and when Kenya gained independence, made sure he was sidelined in the government and prevented from succeeding Kenyatta.

L.B Walsh Atkins, who served as British Secretary of State, wrote in a confidential telegram in 1964: “Most of the evidence on him suggests that he is thoroughly mischievous where our interests are concerned and I think we all regard him as an almost sinister influence.

The danger of his taking over from Kenyatta seems at this end to be if anything rather more remote than we were beginning to fear during the summer.” Even though they were fearful of Jaramogi, they secretly appreciated his outstanding traits.

Sir Malcolm MacDonald, who transited from being the Governor-General of Kenya to becoming the British High Commissioner to Kenya in 1964 advised the Foreign Office: “One of Odinga’s attractive qualities is his genuine humanity. He feels sincerely for the common under-privileged people; and he really wants to help them. He has charming good humour, disarming candour, gentlemanly courtesy, considerable generosity and native friendliness. He can take criticism as readily as he can give.

Another of Odinga’s strengths is his thoroughly African character. He has not become partially westernised by any period of education in Britain like most Kenyan ministers. As a personality, he is still racy of the African soil, and he keeps in close touch with the ordinary simple African people such as peasants, workers and idlers.”

Also Read:The curse of Kenya’s vice presidency

MacDonald went on to advise that Odinga was never a communist and only turned to the East after the west started supporting his main political rival Tom Mboya. “Again with characteristic frankness he has said privately to me on more than one occasion that if the communist had been his rival’s (Tom Mboya) supporters, he would gladly have opposed them and supported the Americans, the British or anyone else who came to his aid.

Despite these views on Jaramogi not being an ideological communist, the west was not ready to take any chances with him, especially with the large European population and many Western investments still in Kenya in those early years of independence.

However, things changed in 1990 when the west started looking at him as a possible ally. With the end of the Cold War, the west stopped treating their former allies, such as Moi, with baby’s gloves and became sensitive to issues such as corruption and human rights abuses. Local agitators such as Jaramogi became their new allies in the push for reforms.

On February 13, 1991, he announced the formation of a new political party the National Democratic Party whose first objective he said was to secure the repeal of Section 2A of the Kenyan Constitution, which made Kenya a one party state.

The move received so much support from western diplomats that one of them secretly sought to know from media houses why they had kept off the event. “The Nation has told us that their silence was a result of a directive from State House,” wrote the diplomat.

With the registration of the NDP seeming impossible, Jaramogi became one of the founding members of Ford, a pressure group whose main aim was to agitate for political and constitutional rights. But typical of Kenyan politics the new group was soon riddled with tribal and personal rivalry after the government allowed multipartysm on August 9, 1991, diminishing the hopes of many who had wished for the forum to produce one candidate to square it out with president Moi of Kanu.

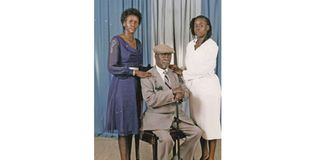

Jaramogi Oginga Odinga with daughters Wenwa and Ruth.

Even though Ford was formed when Kenneth Matiba was away in London receiving treatment, some Kikuyu elites were secretly putting pressure on him to vie for the Ford leadership position against Odinga.

On the same token as Matiba himself would later reveal during a private meeting with officials from the Foreign Office, during his hospitalisation in London some of Jaramogi’s allies led by Paul Muite and Gitobu Imanyara had visited him and tried to convince him to stand down but he dismissed them. On May 2, 1992. Eventually, Matiba returned from London and openly announced his candidature.

The following day, as he retreated to his home after being away for almost a year, a private meeting was held at the British High Commissioner’s residence attended by Jaramogi and some of his Ford allies, key among them Luke Obok and George Khaminwa. Also present was Lord David Steel the former leader of the British Liberal Democratic Party who also served as the Presiding Officer of the Scottish Parliament held a meeting with Odinga.

When Steel sought to know Jaramogi’s views on Matiba’s candidacy, Odinga was very dismissive, describing Matiba as a good friend but he was “coming from the hospital bed”. He added that some of Matiba’s supporters were “dreaming that he can be president”, and expressed fear that Matiba could collapse and die because of “unfair” pressure from such people.

In the record of the meeting marked “secret”, Jaramogi observed that if left to recover, Matiba’s condition would improve and he could “play his part… somewhere”. He further revealed that according to the rumours he had heard, Matiba’s concentration wandered after an hour or so.

Matiba was equally dismissive of Jaramogi’s candidature when he visited London one month later on his way from America. When officials at the East African Department sought to know his views on Jaramogi, he replied that Jaramogi was “far too senile” and that he was the only person who was capable of solving Kenya’s problems.

He even became more dismissive when the officials proposed to him that he should consider serving as Jaramogi’s vice-president. “He was hurt when I asked whether he would be prepared to run as vice-president to Oginga Odinga. He said if he was not selected he would not run at all. His hotel and farming interests were doing very well and he was only involved in politics because of popular demand.”

Although some of Matiba’s friends believed he held the key, they wanted him to be a bit flexible and consider supporting Odinga. They were of the opinion that a compromise was needed if a credible opposition was to be mounted against Moi. For instance, on August 18 1992, John Njoroge Michuki, a key Matiba ally who later served as Cabinet Minister, visited Sir William Tomkys, the British High Commissioner, and asked him to persuade Matiba to drop his hardline stand.

Michuki went as far as asking the High Commissioner to contact Lord Davin Owen, a great British friend of Matiba, to intervene and persuade his friend to temper his arrogant egotism in the interest of opposition unity.

“I told Michuki, that I was not in the business of advising the opposition on how to run their affairs but I was concerned as he was over the dangers of their present disorder,” wrote the British High Commissioner who went on to advise the Head of the East Africa Department in the Foreign Office, “Unless you see an objection, I suggest you convey to him Michuki’s request that he talk with Matiba.”

May to August 1992 saw the crystallisation of two factions within Ford to the disadvantage of Jaramogi who, because of his age, was fighting for his last political chance to lead Kenya. His group was known as Agip House while the Matiba/Martin Shikuku was known as Muthithi House.

The inter-factional suspicion was heightened when Shikuku, a key Matiba ally, agreed to meet President Moi at State House. The visit, coming at a time when the opposition was determined to remove Moi from power, attracted a huge outcry, and it is widely believed that it played a great role in weakening the opposition. Jaramogi, campaigning in Mathare, condemned Shikuku’s visit and described him as over ambitious.

For the first time, declassified documents marked “restricted” reveal that Shikuku was coached at the US Embassy before he left for State House. The Americans were keen on capitalising on the visit to pass their message to Moi.

As a result, they briefed him on a number of issues, key among them was the proposal that Moi should resign in exchange for an amnesty, guaranteeing him protection from prosecution. However, when the Butere MP got to the house on the hill, he concentrated on the rest of the brief but failed to make the key proposal to Moi. The Americans were so annoyed with him for almost saying nothing.

The British, who had been informed about the proposal by the Americans themselves secretly criticised it terming it as “absurd” because Moi was going to win the elections anyway because of disunity in the opposition.

One official wrote “That the Americans should advance it suggests that even in Smith Hempstone’s absence they are out of tune with our findings here, that given the present anarchic state of the opposition, Moi is persuaded that he and Kanu will win free and fair.”

Shikuku was consequently suspended by the Ford steering committee for holding an unauthorised meeting with Moi, and Gachoka was nominated interim Secretary-General in his place. A couple of months later, Shikuku and other members of the Matiba faction announced the suspension of Jaramogi as interim chairman, replacing him with George Nthenge. The eventual result was the division of Ford into two political formations – Ford-Kenya led by Jaramogi and Ford-Asili led by Matiba.

The Jaramogi Oginga Odinga Mausoleum at Kang’o ka Jaramogi in Bondo, Siaya County. PHOTO | FILE |

In a sign of growing concerns over disunity in the opposition, that same month Masinde Muliro visited London where he was given a strict message to deliver to Ford leaders. The newly declassified files reveal that at the private meeting held at the Foreign Office on August 14, 1992, Mark Elliot the British Under Secretary of State told Muliro to inform the opposition leaders to front one candidate, otherwise Moi would defeat them fairly and plunge the country deeper into dictatorship and corruption.

Unfortunately, Muliro never delivered the message as he collapsed and died at Jomo Kenyatta International Airport upon his arrival. Secretly, Mwai Kibaki, who had resigned as Cabinet minister to form the Democratic party, was being pushed by some diplomats to consider working with Jaramogi in case Matiba went it alone.

Kibaki was open to a post-election deal as highlighted in the record of his meeting with a British diplomat. In case Odinga won without a majority, then he was open to cut a deal whereby he would be the prime minister and Jaramogi the President. To this end, he proposed the constitutional amendments that prevented coalition governments should be repealed.

To shore up his presidential bid, Jaramogi was desperately seeking Kibaki’s support, but at the same time thought he was too laid back. During his meeting with Lord Steel at the High Commissioner’s residence, Jaramogi had described his relationship with Kibaki as “on talking terms, not hostile”, but complained that he was “too gentle” and avoided confrontation.

The opposition remained fragmented, largely devoid of vision and was defeated by Moi in the elections held in December 1992. Jaramogi finished fourth and two years later, died of age-related complications in January 1994.