In this picture taken on October 14, 1978, President Daniel Arap Moi weeps at State House where the body of Mzee Jomo Kenyatta lay in state.

On January 27, 1990, as President Daniel arap Moi arrived in the wintery London aboard Kenya Airways flight KQ106 serviced by Airbus 310, a diplomatic tiff over his security and escort had just cooled down.

Moi was transiting London on his way to the United States to attend the Annual Congressional Prayer Breakfast in Washington DC.

Despite numerous pleas by the then-Kenyan High Commissioner to the United Kingdom, Dr Sally Kosgei, that the President be provided with adequate security, since he was a key target for the Somalis, the British totally refused and only provided one policeman on the grounds that the potential threat against his life in London was very low.

Normally, such brief stopovers are categorised as private visits, and it is the responsibility of the visiting leader to make his own plans, which are agreeable to the host country.

In such visits, the role of the host country is limited to providing customary courtesies and other facilities it may wish to offer.

Things such as one police motorcycle escort, which the British were initially hesitant to offer to the leader of a friendly Commonwealth country such as Kenya, could be considered as basic courtesy.

Two weeks before Moi flew to London, Dr Kosgei wrote to the Foreign and Commonwealth Office.

“I shall be most obliged if you could kindly arrange for the provision of police escort at arrival and departure, including traffic police to clear the way as we have experienced difficulties in the past,” she wrote.

The request was outrightly rejected by the Foreign Office, which cited overstretched resources. The argument was that Moi was at a very slight risk of harm during his brief stopover.

“The Foreign Secretary sees no grounds for supplying round-the-clock armed protection for President Moi, unless there is new evidence of a serious threat to his security. Dr Kosgei’s letter does not provide this,” wrote J.S Wall, Private Secretary to the Secretary of State.

On the question of police motorcycle escort, a telegram marked “confidential” stated: “The police will not provide motorcycle escorts unless they are also giving the VIP concerned full protection.”

The new policy on VIP protection had been ratified by the British Cabinet in 1989, on the grounds of overstretched resources. It dictated that the level of security protection for visiting dignitaries was to be strictly based on the assessment of potential threat.

“We cannot allow police resources to be tied up unnecessarily for private visits where the threat assessments are very low,” wrote Wall in reaction to Kosgei’s request.

“The appropriate agencies will reassess the threat to President Moi nearer the time of his visit, but the likelihood is that they will not consider him at high risk in this country which would be necessary before he qualified for armed personal protection.”

Although the Foreign Office cited limited resources as the reason for limiting VIP protection, the truth is that the policy was part of the West’s changing attitude towards its former strategic allies who had been instrumental in the fight against Soviet penetration in the Third World.

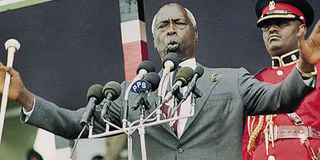

The late President Daniel Arap Moi.

At the peak of the Cold War, these leaders were treated to red carpets and horse-drawn carriages whenever they visited Western capitals.

With the Soviet Union crumbling faster than expected between 1989 and 1991, Moscow shifted its focus from Africa and prioritised addressing the problems back at home.

To the West this loss of interest by the Soviet meant that Communism was no longer a threat to their interests in Africa. And, consequently, the immoderate courtesy they had all along extended to leaders such as Moi quickly dissipated.

Nevertheless, with her request having been turned down, Dr Kosgei decided to write directly to the Prime Minister to intervene.

“I have the honour to inform you that my President will make two transit visits to the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from Saturday, January 27, to Monday, January 29, 1990, again from Friday, February 2, to Sunday, February 4, 1990, the President will be travelling to the United States of America and back.

“Prime Minister, I have been informed that due to constraints in allocation of resources and personnel, it will not be possible for your government to provide President Moi with 24-hour armed security and police motorcycle escort.”

In the letter, Kosgey appreciated all the difficulties and expenses involved especially as London was a major transit place for many heads of state and government but pleaded for special consideration to be given to Moi.

“I am compelled to make a special appeal to you on behalf of my President in the hope that possible problems could be avoided. In the last three years, President Moi has travelled to London or transited through London five times. My experience during those visits has been that it is vital for the President to have 24-hour armed protection.”

To justify her request, she cited one incident when Moi was caught up in traffic while on his way to London from Heathrow Airport.

“Travelling to and from Heathrow is extremely difficult without motorcycle escort. On one occasion, when it was difficult to get motorcycle escort on a busy afternoon, the President experienced terrible difficulties getting into London from the airport.”

She warned that such “experiences together with fear of security problems may cause President Moi to review any transit visits through London, which would be sad as he likes to visit this country whenever he has the opportunity.”

In a subsequent meeting with Harvey of the Protocol Department, Kosgei claimed that the Somalis in London posed a serious potential threat to Moi.

According to her, this problem was related to poaching on the Kenya-Somalia border and other political problems between the two countries. She considered it highly likely that the Somalis in London would want to “have-a-go” at President Moi if the opportunity presented itself.

Following her concerns, the East African Department in the Foreign and Commonwealth Office telegrammed Sir John Rodney Johnson, the British High Commissioner in Nairobi, seeking his advice on how the refusal to grant Moi police protection and motorcycle escort could affect Kenya-UK relations.

“It would be helpful if you could send an immediate telegram with your comments on what damage if any could be caused to Anglo-Kenyan relations by this decision.”

Johnson responded the following day with a brutal telegram in which he warned that the policy could result in a serious diplomatic fallout between Kenya and Britain, and supported Kosgei’s views that Moi was under constant threats from Somalis and dissidents in the UK.

“Moi has a high profile within the Kenyan community, whatever the status of his visit, and the threat he perceives from dissidents and Somalis remains constant whatever the nature of his programme. The Somali community in London is bound to know about his transit,” he advised.

“I believe that providing a single police motorcyclist on arrival and departure would go a long way to allay the difficulty of not giving Moi full protection. If we cannot meet even this Kenyan requirement, I foresee this problem becoming a nagging irritant souring Anglo-Kenyan relations.

"We have enjoyed unparalleled cooperation and security precautions from the Kenyans over official and private visits over the past two years. This will not last if we are perceived as being too miserly to afford Moi a modicum of public respect when he comes to London.”

The British High Commissioner further warned that Kenya could even retaliate by denying British military training facilities in Samburu.

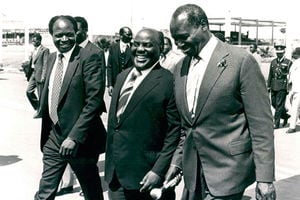

President Daniel arap Moi greets supporters after he was sworn in for his final five-year term.

In Johnson’s own views, there was no way Kenyans were going to tolerate their President being treated with discourtesy while senior members of the royal family and the British Secretary of State were accorded adequate security whenever they visited Kenya.

In conclusion, he wrote: “We shall be spoiling the ship for the ha’porth of tar. Relations would be damaged. I strongly recommend that urgent consideration be given to revising this decision in time for President Moi’s forthcoming visit.”

Johnson had worked in Kenya as a District Commissioner in Central between 1955 and 1963, long before he returned to serve as British High Commissioner between 1986 and 1990.

In fact, before his diplomatic posting to Kenya, there were some doubts within the Foreign Office on whether he was the right choice because of his past service in the colonial government, which could result in him being hated.

But on the contrary, he struck close friendship with President Moi and other senior members of the government whom he had known during his early years in Kenya.

It was therefore not surprising that he was taking a firm stand in support of Kenya, a country he understood its people and its leaders.

In view of his assessment of the possible political repercussions, the Foreign Secretary reconsidered his position on Moi’s visit and agreed to provide a motorcycle escort.

“He believes we can largely allay Kenyan concerns and avoid potential political damage by providing a motorcycle escort for President Moi from and to the airport,” wrote the Foreign Secretary’s private secretary.

However, he still saw no grounds for providing Moi round-the-clock security unless the Kenyans could justify the threats. Instead, one armed protection officer described as “liaison officer” was to receive Moi at the airport and also make periodical visits to his hotel to liaise with Kenyan security officers.

A similar officer had been provided to Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe during his visit to London.

Former President Daniel arap Moi welcomes ODM leader Raila Odinga in his Kabarak home on April 12, 2018. PHOTO | COURTESY

“Like President Mugabe, Moi is coming here privately with no public engagements. The current threat assessment is that like President Mugabe, President Moi is at slight risk in this country,” wrote DCB Beaumont from the Protocol Department.

Following a review of the arrangements for President Moi’s visit, the Prime Minister was advised accordingly, and on January 26, he wrote back to Dr Kosgei to inform her about the arrangements put in place, which included the provision of a motorcycle escort and one armed officer to liaise with Kenyan policemen guarding Moi. This was followed by a meeting between Kosgei and Harvey.

According to the record of the meeting marked “restricted”, Kosgei expressed her satisfaction with some of the measures put in place and thanked the British government.

While expressing her hope that the officials did not consider her request for motorcycle escort for Moi as being fussy, she revealed that on one occasion President Moi’s motorcade got lost for 10 minutes on the way to Heathrow.

Harvey assured her that the protection was being provided based on the assessment of potential threats, also stressing that if anything the Parliamentary and Diplomatic Protection Group of the Met Police had an average response time of one-and-a-half minutes, and could therefore be called into action at the slightest hint of trouble.

President Moi arrived at Heathrow on January 27 at 3pm and not 5.30pm as expected. He was described as “being in excellent spirits and very happy about the arrangements for his visit”.

Even though it is easy to accuse western countries for their callous treatment of African leaders by huddling them in buses, the leaders themselves with their huge delegations which put strain on the host countries’ resources are equally to blame.

For example, while Moi’s visit was described as private, his delegation was made up of 88 people, most of them joyriders.

In a country like Britain, where the PM and the monarch are driven in a motorcade of three vehicles, Moi was rolling in London in a motorcade of 12 vehicles; a very normal sight in Africa but very strange to most Westerners.

Nevertheless, the British accorded them the courtesy of five police outriders to guide them through the traffic.

The late Daniel Arap Moi.

“The police provided a five-man motorcycle escort to accompany the President’s large entourage,” wrote R. Edis of the East African Department.

Moi would again transit through London on his return to Kenya from the prayer breakfast in America.

Following the success of the short visit, Kosgei wrote to the Foreign and Commonwealth Office to thank them for their efforts and assistance.

British officials parted themselves on the back for averting a diplomatic fallout without compromising the new policy on VIP security.