Premium

How Kenya fared when the Spanish flu came calling

Spanish Flu took quite a toll on the world, with 500 million people infected and about 20 million to 100 million others believed dead in three successive waves between 1918 and 1919. GRAPHIC | NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- The disease took quite a toll on the world, with 500 million people infected and about 20 million to 100 million others believed dead in three successive waves between 1918 and 1919.

- Spanish Flu presented itself as a high fever, a wet cough with white sputum, headache and joint pains, and lasted about eight days before turning fatal.

- It first cropped up in the winter of 1915/16, taking years to smoulder before spreading to the entire world.

In September 1918, a ship from India docked on the Kenyan coast. There was nothing untoward about this, save for the fact that it may have ferried one of the deadliest scourges of that time: influenza, then referred to as the Spanish Flu. The disease took quite a toll on the world, with 500 million people infected and about 20 million to 100 million others believed dead in three successive waves between 1918 and 1919. It remains the deadliest pandemic in human history.

Spanish Flu presented itself as a high fever, a wet cough with white sputum, headache and joint pains, and lasted about eight days before turning fatal. Interestingly, researchers traced the onset of the so-called Spanish Flu to a military camp in Etaples, France, during the First World War.

SPANISH FLU

It first cropped up in the winter of 1915/16, taking years to smoulder before spreading to the entire world. The virus was referred to as the Spanish Flu because it was in Spain that researchers first identified it as a new kind of respiratory infection. The disease bore a likeness to pneumonia.

As the world contends with the wildfire spread of Covid-19, it is intriguing to note that China was among the least affected by influenza in 1918.

This led to speculation that it must have originated from there. Chinese labourers were routinely shipped to British and French front lines in Canada, a move that historian Mark Humphries of Canada’s Memorial University claims played a central role in the spread of the disease. Other reports state that it began in Kansas, United States of America (the US) in March 1918.

What is not up for debate is that the influenza determined how Western societies view matters healthcare. The US put the health of their workforce in the fore, instituting comprehensive employer-based insurance schemes.

Russia became the first country to implement a centralised healthcare system for its citizens in 1922. Germany, France and the United Kingdom (UK) followed. The fate of many underdeveloped countries lay with these powers. How did influenza affect the natives of their colonies?

Kenya was a colony of the UK during the spread of the pandemic. The Coastal province of Seyidie held great significance to the colonial power and maintained good administrative and health records.

However, as a report by the Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease Journal in June 2019 reveals, vital documents that would paint an accurate picture of the burden of influenza on Kenya in the years after initial infection are scant.

WORLD WAR 1

The period 1918/19 saw soldiers from World War I discharged from their duties. Some would go home, while others would settle in the newly acquired territories. Many of these soldiers were already infected, and included indigenous Kenyan men that were part of the Carrier Corps — a military labour organisation that drafted about 400,000 African men to provide support services in the frontline in World War 1.

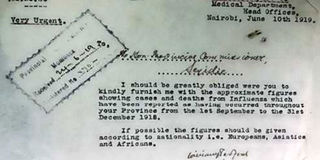

A letter sent by the Coast provincial administration to the Acting District Commissioner in Malindi, requesting for data on influenza-related deaths in November 1918. PHOTO | KENYA NATIONAL ARCHIVES

It’s speculated that upon return, they spread the virus from the seaports and into the main lands by water, road and rail.

The disease affected natives and settlers alike. For appropriate action to be taken, the government needed statistics to measure the burden of a disease on its population.

Reports on the pandemic in Kenya were largely informal, with communication between provincial commissioners and the chief medical officers proving ever so crucial to providing the data needed for the colonial government’s planning. They reached out to the district leadership to monitor and regularly report on the progress of the outbreak.

Information on the state of the native population was collected through weekly barazas (public meetings) and liaisons with village elders.

Authorities promptly began recording data on the number of cases and deaths from influenza, subject to several reminders from the province.

The earliest correspondence dates back to November 28 1918, where the provincial commissioner requested for data from the district commissioner in Malindi describing the mortality rate in the area.

The second and most crucial is a letter from the authorities in Nairobi in June 1919, requesting for data on the cases and deaths as a result of influenza in the tail end of 1918. “If possible, the figures should be given according to nationality,” the Principal Sanitation Officer wrote.

The findings of Fred Andayi, Sandra S. Chaves and Marc-Alain Widdowson of the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention in Kenya paint a grim picture of strife at the intersection of colonial rule and a global pandemic.

SECRETIVE

Approximately 4,593 deaths were recorded in five districts between September and December 1918, together with about 31,908 new cases of influenza. The numbers could have been higher.

“Natives are most secretive about illness and death among their people,” wrote an assistant district commissioner in January 1919.

Reports alluded to the mortality rate being highest among the native population, despite their reluctance to provide authorities with information. Even so, visits to healthcare facilities after the virus was introduced shot up in the years after the first infection was recorded. In Taita-Taveta district, approximately 50 people died each day.

Meanwhile, in Nairobi, confusion around a mysterious disease abound. The East African Standard, the only newspaper in Kenya at the time, made no mention of the disease until mid-October 1918, when the sudden death of a Captain Grigg after a bout of pneumonia alluded to the origins of the illness in Mombasa. Grigg was a treasured member of the Nairobi social scene, and had taken a trip to Mombasa for a brief holiday. It was there that he was struck down by the prevailing pneumonia that had then been “sweeping the country”.

News on this strain of pneumonia was overshadowed by wartime chatter. Then, on October 24, a page 2 column in the newspaper titled: “Our Epidemic” finally broke the news on influenza: its origins, symptoms and details on the only treatment at the time — bed at once and management of the symptoms as they arose.

Pharmacies started advertising quinine and cinnamon tablets targeting customers that feared “Spanish Influenza” or “Nairobi Throat”.

By October 29, comprehensive reports started rolling in. Hospitals in Nairobi were “very hard pressed” by the epidemic, and had put out advertisements seeking volunteer nurses. The Asian community were particularly compromised, as the flu eventually progressed into pneumonia, killing them at a faster rate.

23 FUNERALS

In one week, they had 23 funerals, and 11 more had died by the time the paper went to press. The outbreak appeared to have been facilitated by a fundraising ball hosted by the Red Cross. The correspondent who wrote the article hoped that the coming rains would “eliminate the scourge”. The paper also began publishing a “Local Sick List” of residents in Nairobi that had been infected with the flu. The quarantine extended far and wide, as the Union of South Africa had issued a travel ban on passengers from British East Africa in light of the illness.

Back to the coast, where the colonial administration was overwhelmed and understaffed. The disease paralysed operations, with officers failing to turn up at work due to unprecedented illness.

Provision of public services was delegated to native carrier corps, who would help the government in distributing food, medical supplies and information. Health facilities had to contend with a burden of about 300 new cases daily. Recommended medication included three spoons of paraffin, starch and milk, as well as preventive medication for health workers, such as gargling potassium permanganate.

With little to no assistance from the colonial administration, it is left to the imagination what these facilities had to do to manage the influx of patients, what with a limited reserve of medical supplies according to anecdotal evidence.

Kenyans were affected in a different capacity. The disease rendered them incapable of tilling land or performing any official duties. They had resorted to working for the settlers to meet the rising cost of hut tax, but could no longer do so, resulting in the loss of their jobs.

“These natives are now suffering from reduced vitality and possibly cannot at least for the moment pay for assistance, as well as hut tax,” wrote Talbot Smith, then district commissioner for Taita-Taveta.

FOOD SHORTAGES

The people’s inability to work led to food shortages and economic strife. Industries like the Kebal Fibre Estate and Haubner Farms in Taita-Taveta district were adversely affected and shut down indefinitely.

The labour shortage as a result of the spread of the disease led to great economic losses. A lack of seed supply and poor weather conditions in 1918 also contributed to the food shortages, manifesting in poor nutrition among the native population, who depended on subsistence crops to survive.

Further, the stark inequality between them and the settlers in terms of the standard of living devastated the population. Malnutrition meant their immunity was compromised. The elderly appeared to have been marginally affected, despite there being little data on the ages of the patients. The administration worried that overcrowding in Malindi, Mambrui and Roka, as well as a scarcity of clean water, contributed to high mortality among native Kenyans.

The fatalities recorded appeared to have been lower in areas that had more developed infrastructure, as opposed to districts like Mombasa that maintained communication with the outside world.

Districts like Nyika (present day Kilifi) and Vanga (present day Kwale) had very little marine traffic, meaning, there was little to no contact with infected passengers aboard incoming ships.

The steady rise in hospital visits in the years after the pandemic until 1925 leaves to speculation whether the government of the day was successful in the management of the pandemic.

Even so, the situation was not as dire as it was in 1918. By 1920, doctors had developed improved mechanisms to deal with the disease, recording an abrupt decline in influenza-related deaths. Armed with new policies, the worst seemed to have been behind them.

MORTALITY

The fast and deadly spread of Covid-19 reminds the world of the morbid significance of pandemics. They force the human race to act fast when threatened with sudden death and flood light on the damaging effects of inequality, especially when it comes to matters survival.

The inaccessibility of vital resources — adequate healthcare, housing, sanitation and food — is exacerbated by the spread of a pandemic. Government stability is tested by the spread of this disease and the interventions they can swiftly put in place. The social elite reveal their true selves, giving meaning to the saying “every man for himself, and God for us all.”

However, if history is anything to go by, mortality is universal: neither race, social status or wealth matter when it comes.

The East African Standard (with correspondents from the Mombasa Times and Uganda Argus) was the only newspaper in Kenya at the time. It was established in 1902.

Readers were predominantly white settlers. The 16-page publication featured stories oriented towards that audience, such as wartime chatter from overseas on the British and German invasions.

This meant that crucial information on preventing the infection was only available to those who could afford the paper and, moreover, understood English.