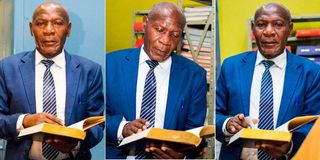

Deputy Director of Public Communications State Department of Basic Education Kennedy Buhere during an interview on February 23, 2024 at Nation Centre in Nairobi.

If Kennedy Buhere were a book, he would be the heavy-duty hardcover type: enduring and primed for the long race.

And nicely holding together, with a tough spine to boot.

However, he cannot be a book; he is a fan of books.

Mr Buhere is the head of communication at the State Department of Basic Education.

To say he is crazy about books would be to imply that he goes gaga when he lays his hands on a title he is yearning to read — which he does.

He will not wait to treat his eyes to a good book, especially the classics. He drools when he comes across a book by one of the great philosophers. He feels like Alice in Wonderland when he sees a biography of a great statesman or woman.

He also loves to savour the folklore of ancient civilisations. Speeches also tug at his heartstrings, the same as classical poetry.

Novels. Plays. Poetry. Folklore. Mythologies. He has a long list of literature that makes him happy.

Due to that constant quest for good books, he is one of the people who keep used booksellers on the streets of Nairobi in business.

“I have bought most of my books from the street book vendors. Some know my taste. They notify me. I buy any book that meets my aesthetic interest there and then. I buy some on credit if I happen not to have cash,” he says.

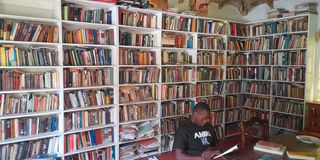

A library that he has built at his rural home for books is reminiscent of an institution’s library. Tomes and tomes of books are packed on the shelves, and a book lover will be spoilt for choice.

He has a few rules regarding his books, among them that he has always allowed his children or the children he has housed to have unfettered access to them.

“I have allowed (them) to access them without let or hindrance. A book that is never touched is not useful. So, I let them be as careless with the books as possible,” he says.

He also habitually lends books to parents and guardians for the benefit of children with reading difficulties.

He also gives out books to children who love reading but have no books to read; the same as journalism students under his supervision while on industrial attachment.

Deputy Director of Public Communications State Department of Basic Education Kennedy Buhere during an interview on February 23, 2024 at Nation Centre in Nairobi.

The book-buying bug bit him in the early 1980s when he was a Form Two student at Kivaywa Secondary School. He has not stopped since.

“I used my pocket money to buy a storybook each term when we opened school,” Buhere recalls

“A few of us decided to go back to school (after the holidays) with a novel, which we used as bait to read books from friends and acquaintances. This is how I began the craze of buying books.

"I remember buying Across the Bridge, Love Root and A Girl Cannot Go on Laughing All the Time. I bought Mwangi Gicheru’s Across the Bridge in January 1980. It has just been published in November of the previous year,” he adds.

He says he has no particular book-buying routine, just buying as and when a good book is available.

So, how many books does he have after buying titles for nearly five decades?

“Just like I cannot remember or count the number of books I have read, I don’t know how many books I have bought or which are in my home library. It’s like asking a person from a pastoral community how many cows he has. My books are the equivalent of cows. I don’t know how many I have,” he says.

The books he reads have influenced his life in different ways, and when we ask him about the titles that have had the most impact on his life, the first one he mentions is Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s Weep Not, Child.

“It, for the first time, helped me understand that education can be a tool to change things,” he says.

He also reveals that he has kept three novels with him for more than 40 years. They are So Many Hungers by Bhabani Bhattacharya, The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck and The Plague by Albert Camus.

“The books are about a people who suffer painful deprivations,” he says.

“The other book that has had a lasting impact on me is The Federalist Papers, written in 1787. The book, written by three founding fathers of the US – James Madison, John Jay and Alexander Hamilton – explains the basis of a modern government, relations within the coordinate organs of government, its relations with the people and how it should govern the public affairs of the country,” he adds.

A chat with Mr Buhere about books quickly opens the pages of other chapters like Kenyans’ reading culture and what can be done to make readers out of Kenya’s young generation.

Meeting him, you encounter an extension of his Facebook persona, where he every so often posts about the need to have readers in society. He is a proponent of reading for leisure.

“Reading implies leisure. Study is for utility, with a defined end in view,” he quips.

His passion for reading, he says, started when he knew how to recognise a whole word.

“That was in Class One, eons ago,” he says, recalling how mesmerised he was to be able to read words like “mama”, “Omo”, “Kimbo”, among others.

He started his primary education at Lukume Primary School in 1972 in present-day Kakamega County.

This is where, thanks to the school library, he learnt to read and had access to books like Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves and the myths of Daedalus and Icarus, King Midas, among others.

After sitting his Certificate of Primary Education exams in 1978, he joined Kivaywa, where he picked up the book-buying habit as a Form Two student.

After completing his O-levels in 1982, he joined Kakamega School, where he got his A-level schooling until 1984.

“I joined the University of Nairobi where I studied for a BA (bachelor of arts) degree in government and literature, and graduated in 1989,” says Mr Buhere.

He had a short stint as a board of governors-employed teacher at Kolanya High School before he became an information officer in 1990.

In 1998, he joined the Kenya Institute of Mass Communication to train in journalism. In 2005, he returned to the University of Nairobi for a Master’s in Communication Studies.

“I have since worked in Eldoret, Kerugoya, Butere, and Busia in the field and, since 2007, at the Kenya News Agency newsroom, Ministry of Immigration and Registration of Persons, Ministry of State for Public Service and now at the Ministry of Education,” he says of his career journey.

Throughout that journey, he has been buying books, some not even remotely related to what he was studying or handling in his day-to-day engagements.

“I have learnt that education and schooling are not the same. One can have modest schooling but be well-educated through reading appropriate books that properly educated people ought to read.

"Benjamin Franklin and Abraham Lincoln did not have what we today call secondary education. Winston Churchill and Tom Mboya did not have a university education, yet they had capabilities we associate with university education. Secret? Reading books that educated people in the past read,” he says.

He says the most he has ever spent on a book is Sh2,000, and adds that one gem he bought so cheaply that he couldn’t believe it is a copy of Paulo Coelho’s The Alchemist.

“I bought the book in Kibera in 1997 for Sh40,” he says.

Through reading widely, he says, he found ways of tackling tasks assigned to him.

“Reading has helped me to quickly understand the visions, purposes, impediments and opportunities the different ministries are established to actualise or deal with in the process of serving Kenyans. It has given me the confidence to relate with different people, be they in the highest or lowest ranks of an institution. Reading, above all, makes you a humble person,” says Mr Buhere.

Our conversation on how to make book lovers out of Kenya’s children makes Mr Buhere animated. When we ask him whether Kenyan children and Kenyans in general are reading enough books, his first answer is “yes and no”.

He recalls the 1970s and 1980s when primary schools would have book boxes and book corners to cater for the needs of learners who wanted books to read.

“One would like to ask the (school administrators) where the books went,” he says.

A man reads a book inside the home library belonging to Kennedy Buhere in Kakamega County.

“Also, most parents, particularly middle-class parents, value other things than books outside the textbooks. They are ready to buy textbooks the teachers recommend but either they are loath to buy non-textbooks or don’t know the value of non-textbooks in the education of their children,” he adds.

Mr Buhere also laments that secondary schools are not paying enough attention to the kinds of books they stock in their libraries. He feels like most schools have relegated reading to leisure as they elevate the reading of textbooks.

“I have visited some of these libraries. Most of them now have textbooks,” he says. “In this context, are the children reading enough? No. They are surfeited with textbooks and, regrettably, with textbooks, you study its contents; you don’t read.”

He notes that the 8-4-4 curriculum, now being phased out, encourages reading for leisure, giving provisions for learners to interact with newspapers, magazines, poems, and short stories, among others.

“Kenya’s education system has given reading for leisure a pride of place. In the school calendar, the school hours as contained in Section 84 of the Basic Education Regulations, 2015, provide the widest possible latitude for extensive reading — in school, at home, during half term and school holidays.

"Any programme that takes away time for extensive reading has no place in the education system of Kenya. I have not come across any document on education that bans extensive reading,” argues Mr Buhere.

He believes that the number of children who are given the right material for reading by their parents and their schools is “far between”.

“All children in Grade Four and beyond ought to be given opportunities to read books; books suitable to their grades. If some children cannot read at the grade level they have reached, they should be given books slightly below their respective grades to build their reading skills,” he says.

“We have a duty as adults to ensure all children can read, whatever the impediments. Reading is not a natural human activity, like talking or walking. I may be naïve on this. However, I fervently believe that every child, regardless of his or her cognitive ability, can read when skillfully introduced to reading,” he adds.

Goes on Mr Buhere: “I think the adult population owes a duty to children to expose them to the rich cultural heritage of all civilisations. The finest and the most transformative utterances or emanations from the greatest minds are in books.”

Then we delve into the topic of Kenyans and their reading culture, a subject that has expressed itself in various ways in the past.

A 2023 study by data firm Stadi Analytics and the Writers Guild Kenya found that at least 85 per cent of residents living in Nairobi read regularly and that more than half did so daily. The reading culture was found to be significantly influenced by several factors including income, gender, and age.

The study found that women preferred to read fictition while men read more non-fiction — mostly books, magazines and newspapers. Another finding was that older people above the age of 45 years were more frequent readers than younger ones.

In 2016, the Kenya Publishers Association described Kenyans’ reading culture as wanting.

Its chairman David Waweru said: “The problem with the Kenyan society is that we read mostly for exams, light academic fires and burn books as we dance after ‘completing education.’”

However, Mr Buhere believes the scenario is not that dismal.

“A book vendor on the streets told me that he sold more books during the Covid-19 period than he had ever sold before. And mark you; he doesn’t sell textbooks. Most book vendors in Nairobi CBD don’t sell textbooks. This is a sign that there is a nascent reading culture among a significant proportion of Kenyans,” he says.

He also shares one of his mottos on reading: “In books are the insights and wisdom of our greater ancestors. Reading is the password into their thought systems.”

“Fictional and nonfictional works are full of the wisest and most insightful ideas about mankind and the natural environment,” he adds.

That line sounds weighty enough to make a hardcover book.