Premium

County officials bleeding farmers dry through colonial tax

A customer prepares to buy bananas at the Kangemi market in Nairobi on April 30. PHOTO | DENNIS ONSONGO | NATION MEDIA GROUP

County officials are still using cess, an outdated colonial tax, to impoverish small-scale farmers, a Nation investigation in 15 counties has found.

The tax – ranging from Sh40 to Sh3,000 – is levied on farmers and traders at multiple points as they transport goods to the market by dreaded tax collectors.

Posing as farmers with agricultural produce behind a truck, the Nation team drove through the cess points – from rice and sweet potato farmers in Sirare at the Kenya-Tanzania border in Migori County, to small-scale banana farmers in Kisii, maize farmers in Kitale and miraa sellers in Meru. We also visited Siaya, Kisumu, Kakamega, Bungoma, Trans Nzoia and Uasin Gishu counties before heading to the Mt Kenya region, where we went to Meru, Nyeri and Kirinyaga counties.

TAXATION PRINCIPLES

We came face to face with corruption and gathered evidence on why agricultural produce cess does not satisfy most of the principles of good taxation, such as fairness, neutrality, effectiveness, efficiency, flexibility, certainty and simplicity.

For a start, getting genuine receipts that can be traced back to the county government revenue accounts is as rare as finding honest cess collectors.

Depending on the vehicle that the farmer has – new or battered – the amounts could be negotiated or not paid at all, in exchange for a portion of the harvest such as a few sacks of maize.

ENRICH PEOPLE

Cess has become a disincentive to agricultural production and marketing and a scheme by some individuals to enrich themselves, multiple interviews during our investigation indicated. Aside from the cess fees, traders also have to pay a fee to the county government to be allowed to sell, mostly an average of Sh20.

But the biggest irony of cess tax is that it is levied on fresh produce – processed or manufactured ones are spared – even as the country fights to be food-secure. Dealers in non-food items, some of them non-essential, can transport anything across the country without being required to pay cess.

Agriculture CS Peter Munya at Kilimo House, Nairobi, on July 2, 2020, when he announced sugar reforms and government directives on the importation of sugar and cane. PHOTO | SALATON NJAU | NATION MEDIA GROUP

In a phone interview, Agriculture Cabinet-Secretary Peter Munya termed cess a major problem, “a thorn in my back”.

The CS also took offence at the way the tax is levied, saying it is killing small-scale farming, the biggest contributor to food security and trade.

“It is double, even more than triple, taxation to farmers, and this increases cost of food production for the farmer, which is transferred to the consumer, ” he told the Nation.

“I have been called and witnessed fish coming from Western rotting by the time it gets to the market in Nairobi because of delays on the way.”

CS Munya transferred the blame to the Treasury and the Council of Governors, saying while it is not under his docket, his ministry is under the spotlight about this.

“The governors are always saying ‘we will fix it, we will fix it’ but nothing moves,” he said. “The Treasury is always saying ‘we have a Bill in place to eliminate this’ and it never happens.”

A LIVING

As we drive through the Nyanza counties of Kisii and Migori, it is clear that many are eking a living from small-scale farming – after every 10 kilometres, there is a busy market of some sort.

Onyango Odanga, who trades in cereals and owns a flour milling shop in Migori town, plies the Migori-Sirare route to buy maize on wholesale, which he transports in hired vehicles. Mr Odanga knows he must stop at points manned by people in green uniform who can make or break his business – men, like the biblical Zacchaeus, the tax collector, who demand cess.

From Suba market, Mr Odanga stops at three points before he reaches Migori. At each point, the amount required – from as little as Sh50 to Sh300 – is varied and no receipts are issued to ascertain the amount paid. The lack of receipts, he says, is a blessing and a curse.

“Sometimes it is good that they do not give me a receipt because that means I can plead to pay less than what they ask for, but the problem comes when I encounter their colleagues at the next stop and I have no proof of prior pay, so they ask for money again,” he says.

BUSINESS ‘SPACE’

Mr Odanga does not know the purpose of the fees, and in a fatalistic tone, he says,: “I just want to go about and earn my livelihood, and do not mind parting with some money to have space to do my business”.

This arbitrariness is what exploits the farmer. A 2017 report on the impact of agricultural produce cess on farmers in Kenya by the Cereal Growers Association (CGA) found that the national public policy on cess is unclear and there is therefore a vacuum in guidelines for the collection and utilisation of the tax.

It also found that none of the mandatory County Finance Act and County Appropriation Acts were valid, as they had not been published in The Kenya Gazette.

JUSTIFY COLLECTION

Nevertheless, these instruments were being applied to justify cess collection and without linking the tax to specific services for the payers.

“Multiple and high agricultural cess rates are charged arbitrarily and with no justification for the rates applied, a practice that distorts the market, reduces producer incomes and hence threatens sustainability of production and productivity of the value chains and hurts the rights of producers,” the report notes.

Some governors also use this money as the channel to get jobs for their loyal supporters, some of whose only qualification was meting out violence during election campaigns.

These cess collectors, as the Nation observed, have morphed into little terrorists in the villages targeting transporters, farmers and players in the agribusiness sector.

AGGRESSIVE OFFICIALS

In Oruba, as you enter Migori town from the Tanzanian border, the Nation encountered the cess collectors. The woman and man come with aggression, unsuccessfully reaching for the key in our vehicle. In Dholuo, the man began his conversation with threats.

“You pay, or leave this vehicle here and then come talk to us from the county offices where you will give even more money,” he says.

The man asks for Sh500 for the seven bags of maize we have on our pickup for this investigation, an amount we begin pleading to be lowered – an extremely humiliating process characterised by insults – until it is agreed that we pay Sh300.

A blank receipt is issued to us, after which she requests that we write the amount that we should have paid (Sh500) on it to avoid being charged at the next stop.

The cockiness and arrogance with which the man speaks becomes clear in Kirinyaga where next to the cess collectors are barriers placed by the police, who do not seem bothered by the extortion going on.

Farmers go through this daily, but the results are never as pleasant after that humiliation.

When they have no extra money, they lose their produce, which they can only claim after paying the cess officers.

A 2015 report by the Food and Agriculture Organization shows that Kenya has about 16 million smallholder farmers. Each owned at least 1.2 hectares.

The report notes that small-scale farmers are some of the poorest people in the country.

WORSE SITUATION

“In Kenya, for example, 74 per cent of these houses have a dirt floor, and only 13 per cent have walls made with bricks,” it says. "Few of them have access to electricity for lighting (about 5 per cent), telephone (0.1 per cent), running water in the house (12 per cent) and only 1.5 per cent have proper sanitation facilities.”

More than three years after the Cereal Growers Association report was published, things have only moved from bad to worse. The CGA study narrowed down to eight counties with vibrant agricultural sectors.

These were Trans Nzoia (maize), Kericho (tea), Nakuru (cut flowers) and Narok (wheat).

It also looked at Nairobi (poultry and pigs), Meru (potatoes), Isiolo (other livestock) and Kiambu (coffee, dairy) and a study of legislative processes. The other key finding of the report was that farmers only paid cess when selling their produce in the market, except for wheat and maize farmers, who paid cess on transit to drying facilities.

‘LIMITED CHOICES’

Traders were consistent cess payers and they reflected the payment by reducing the prices paid to producers.

“Traders are able to pass the costs of transactions either to producers or to consumers through price adjustments. Producers and consumers have limited choices in matters of transaction costs; their produce would not secure buyers if they raise their prices too high while consumers would not afford the produce if it is too expensive and would either seek alternative goods or forego the produce altogether,” the report adds.

It warns that if taxation is imprudently applied, it can hurt the interests of both the producers, consumers and even the government itself where agricultural producers divest to non-agricultural enterprises.

‘A DISINCENTIVE’

“When cess is converted from a charge on services into a general tax, or its proceeds do not support payers through service provision, it can be a disincentive to producers and other value chain players; the latter case is what the Cereal Growers Association (CGA) and other stakeholders under the auspices of the Agriculture Industry Network feel is the situation of cess administration in Kenya today,” the report notes.

In Nairobi, the county government charges traders at the major markets between Sh30 and Sh50 per bag of potatoes.

“The smallest truck here carries 80 bags, whereas an FH truck can carry close to 110 bags. That means that we have to pay at least Sh3,000 per day to the county officials here in Nairobi. The FH guys are not lucky as they have to pay Sh5,000 per day,” Mr Mwangi, a truck driver, says.

CONSUMERS AFFECTED

This is not the only cess that they are required to pay. According to Mr Mwangi, when they come from the farm, they are required to pay between Sh1,500 and Sh3,000 to the county.

The traders reiterate that, in this chain, the consumers are the biggest casualties as they are the ones on whom the tax is eventually offloaded.

“This business has too many costs. When it is a bit rainy, the truck cannot access the muddy parts of the farm. Therefore, we have to hire a tractor to do that job,” he says.

Hiring a tractor costs Sh200 while a bag of potatoes at the farm gate costs Sh2,000.

“We have to pay some people to load and sew the bag. That means that when we come to Nairobi, we have to sell a bag of potatoes at Sh4,000 and above, if we are to remain in business,” another trader, who requests anonymity, says.

PIPE DREAM

The drivers maintain that the biggest pain for them is that the county officials tell them that the money they are collecting is to be channeled to maintaining access roads and security at Ukulima Market, two things that remain a pipe dream.

“They collect a lot of money, not less than 100 trucks come into the market. When they tell us that the money goes into maintaining roads, they must be joking with us. Just have a look at this road,” says a trader, who declines to provide his full name, pointing to a damaged murram road.

There is some hope, however, that the tax may be reviewed.

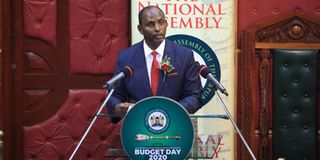

Treasury Cabinet Secretary Ukur Yatani tabling Sh3.2 trillion Budget at Parliament Buildings on June 11, 2020. PHOTO | JEFF ANGOTE | NATION MEDIA GROUP

National Treasury CS Ukur Yatani promised small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) at a conference organised by the Nation Media Group early this year that the government would harmonise fees such as cess that have raised the cost of doing business across the counties. The proposal is for a fee to be paid once at the point of exit.

At the expo, SMEs raised concerns on the introduction of new taxes that were making it hard for them to do any business.

For instance, a maize trader sourcing the grain from West Pokot to Kitale in Trans Nzoia for drying and rebagging before selling in Nairobi or Mombasa incurs three levels of cess.

“If SMEs must be taxed, it should be comfortable, affordable and must be within their reach. Our role is to make sure that the private sector grows, the SME grows,” Mr Yattani said.

Agriculture CS Peter Munya said though the government was keen to resolve the tax burden on SMEs, the biggest problem was the multiple licences paid to numerous agencies both at the national and the county government that were hurting the sector most.