Premium

Justice delayed: Victims take centre stage as ICC opens Kony hearing

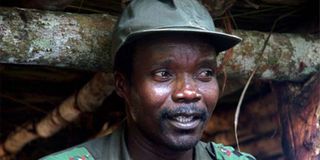

Joseph Kony, leader of Uganda's Lord's Resistance Army.

The International Criminal Court on Tuesday began the first ever confirmation hearing in absentia, for Ugandan warlord Joseph Kony, 20 years since he was indicted for war crimes and crimea against humanity.

But while it opened a door for accountability in one of Africa's atrocious events, defence lawyers said it was opening old wounds.

They argued the case was an unnecessary reminder to victims.

Geoffrey Boris Anyuru, a lawyer from northern Uganda, addressed the Court in Acholi language, Kony's native tongue and the language of most of his victims. He wanted to speak directly to affected communities:

"As far as the population of Uganda is concerned, those in Northern Uganda in particular… the proceedings that are currently ongoing are not trial proceedings. In the end, nobody is going to be sentenced, nobody will be sent to prison," he said.

He warned that victims should not expect reparations soon, even if charges are confirmed:

"Nobody is going to get reparations for any of the suffering they went through. Even if Joseph Kony is arrested and tried in this court, reparations will take time. We are still waiting for reparations from the Dominic Ongwen case, and the Trust Fund does not have the money." He was referring to Kony's leutenant in the Lord's Resistance Army (LRA), the rebel movement that left indelible horrid scars in northern Uganda.

In 2021, the ICC found Ongwen guilty of 61 charges including murders, rapes and sexual enslavement during a reign of terror in the early 2000s by the LRA, led by Kony. The ICC'a appellate court would confirm the sentence. He is now in Norway, serving his sentence.

Ongwen earned a lower penalty (that the usual 30 years for warlords) because he had mitigated in court that he was also abducted by the LRA as a child. Some 100,000 people are said to have been killed by the LRA and another 60,000 abducted and forced to fight LRA's wars.

In Court, Anyuru also cautioned that the ICC’s process risks retraumatising survivors by showing graphic evidence without their direct participation. Some of the survivors live with missing limbs, ears and kin.

"The showing of these pictures… will cause more harm. People are seeing their brothers, their sisters, their relatives. It will retraumatise them."

His defence colleague, counsel Lilian Beatrice Atim, placed the proceedings in the broader context of Uganda’s transitional justice efforts:

"Under the Rome Statute, the primary responsibility for investigating crimes committed in Uganda rests with the national authorities. Over the last 20 years, Ugandans have investigated alleged LRA crimes and implemented reconciliation strategies. We passed the International Criminal Act of 2010, established the International Crimes Division, and tried LRA commander Thomas Kwoyelo. At the same time, the Amnesty Act of 2000 has helped reintegrate fighters, including members of Kony’s own family."

She noted that Uganda’s Parliament is considering a National Transitional Justice Bill to establish a reparations fund for all civil war victims, not just those in ICC cases. But she warned of the bitterness caused by the Ongwen reparations process, where some victims were excluded while others still wait.

"This court can only be a small part of the larger project of transitional justice needed to ensure peace and reconciliation," Atim said.

Together, their interventions underscored the central dilemma: while the ICC can formally acknowledge atrocities, it cannot deliver immediate justice or reparations. Uganda, meanwhile, has pursued its own justice and reconciliation mechanisms, though those too remain incomplete and contested.

For thousands of survivors, this week’s hearing offers recognition of their suffering and a symbolic step toward accountability — but not yet the justice they deserve.

The Court, nonetheless, made history as it opened its first-ever confirmation hearing conducted entirely in the absence of the accused. Judges of Pre-Trial Chamber III — Alexis-Windsor, Iulia Motoc, and Haykel Ben Mahfoudh — convened at 9:30 a.m. to assess 39 charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity against Ugandan rebel leader Joseph Kony.

Prosecutor Leonie von Braun reminded the court: "The dock is empty of any potential accused. Joseph Kony is not present here today. Twenty years ago, other judges of this court issued a warrant of arrest against him. He has been at large for the last 20 years."

The charges stem from atrocities allegedly committed by Kony’s Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) in northern Uganda between 2002 and 2005. They include murder, sexual enslavement, rape, torture, and the forced recruitment of children.

Prosecutors described a campaign orchestrated from the very top of the LRA, citing at least 618 civilians killed at seven displacement camps. "If you are not with us, you are against us," prosecutors said, quoting Kony’s motto.

One chilling entry in a 2004 logbook recorded Kony instructing a commander: "Let Odiambo go and kill Langi tribes from the old to the kids."

The court heard evidence that more than half of nearly 11,000 registered abductees were under 18.

"I was 12 years old when I was abducted, two of my brothers were killed in my presence," one victim testified. "That is how a childhood ends with a loss of family and the forced march in the bush."

Witness P-275 recalled: "I saw children younger than me being trained to shoot with weapons. I knew they were so young because the muzzles of their AK-47 rifles dragged on the ground when they carried them on their shoulders."

Prosecutors also played a 2002 radio interview in which Kony himself admitted that abduction was the LRA’s method of recruitment.

Sarah Pellet delivered an emotional plea: "The victims have waited for more than two decades for this moment. They have waited for more than two decades for their pain to be acknowledged, for their loss to be recognized, for justice to be done in their name."

She recalled harrowing testimonies from survivors still haunted by their experiences. One woman described how rebels shot at her, forcing her to throw down her baby to run for her life. She never saw the child again. Another recounted how the LRA killed her mother by cutting her on the back and neck before setting fire to their home and killing her father during the attack.

Lead counsel Peter Haynes KC questioned the fairness of proceeding without the accused, calling attention to the "empty chair." His colleague Geoffrey Boris Anyuru reinforced skepticism from northern Uganda, insisting: "The proceedings that are currently ongoing are not trial proceedings. In the end, nobody is going to be sentenced, nobody will be sent to prison."

Atim pointed to Uganda’s own reconciliation strategies, including an amnesty program for lower-level LRA fighters, as evidence of national accountability.

This is the first time the ICC has invoked Article 61(2)(b) of the Rome Statute to hold confirmation hearings in absentia. Still, any trial requires Kony’s physical presence.

Despite international manhunts spanning decades — led by the African Union, supported by U.S. forces, and bolstered by civil society campaigns — Kony remains at large, believed to be in his sixties.

For survivors, the hearing has reopened painful memories. One victim put it simply: "When I was abducted, I was going to school and I had a future. Now my dreams are gone."

The hearings continue through September 11. Judges will then decide whether to confirm the charges — another step in a long process, but still far from the justice that victims have sought for more than 20 years.