Motorbikes belonging to boda boda operators parked at Nyayo Stadium, Nairobi on July 25, 2022.

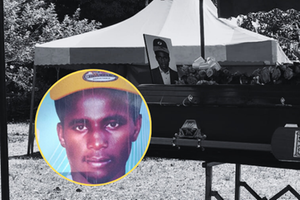

After his younger brother was brutally murdered, Josephat Muthiani quit his job as a financial consultant at one of the local microfinance institutions and joined the boda boda industry.

Obsessed with getting to the bottom of the heinous crime that had robbed his family of a loved one, the 34-year-old Muthiani threw himself into the boda-boda business with unparalleled zeal. He soon rose through the ranks of the Boda Boda Sacco in Emali Municipality to become its secretary-general, a role that made him a key player in the fight against motorcycle theft.

He was occasionally called upon by micro-lenders to help recover stolen motorcycles. On one such mission, he and his boda boda colleagues in Emali town tracked a stolen motorcycle to the Kenya-Tanzania border at Loitokitok, Kajiado County.

But they soon discovered that the tentacles of the criminal gang that killed the riders and stole the motorcycles were long and the individuals at the head of this cross-border syndicate powerful.

The GPS tracker that was guiding them indicated that the motorcycle was moving from Kenya to Tanzania and back again. But when they were 10 minutes away, the motorcycle suddenly stopped.

They were elated, believing they were on the verge of a major breakthrough. To their surprise, when they arrived at the location, all they found was the tracker. "The bike had disappeared," said Muthiani.

Muthiani swears that there was a 'snitch' among them, suggesting that the killing of the boda boda operators and the theft of the motorcycles may have been aided and abetted by other riders.

Ken Onyango, chairman of the Kenya National Boda Boda Association, agrees that in some cases motorcycle theft is a matter of "kikulacho ki nguoni mwako", loosely translated as the enemy is within the ranks of the boda boda operators.

“Some of them (boda boda operators) have ganged up with goons,” said Onyango.

Weeks before this interview, Muthiani and his team would identified one of their enemies within them when they detained three motorcycle thieves.

The three were suspected of killing one rider, injuring another and stealing three motorcycles in two months.

One of the detainees, a Tanzanian, led them to their contact in Emali. This was the person who would alert those on the Tanzanian side whenever a stolen motorcycle was available and needed to be transported across the border.

“We found that it is someone we spend time with on the stage,” said Muthiani.

In 2008, then president, Mwai Kibaki, abolished import duties on motorcycles with engine capacity of 250cc, triggering an increased influx of two-wheelers into the country.

Traffic congestion in Kenya's major towns and bad roads in remote areas made boda bodas an instant hit. The number of registered motorcycles jumped from 3,759 in 2005 to 91,151 in 2009.

But it was the availability of easy money from micro-lenders that sparked the boda boda revolution in Kenya. Suddenly, those who could not otherwise afford to buy motorcycles took out loans, paid an initial deposit of as little as Sh10,000 and got into the boda boda business.

President William Ruto's campaign message of uplifting and dignifying the downtrodden, the so-called 'hustlers', struck a chord with the boda boda operators, whose renegade nature had earned them contempt among the middle class.

President Ruto later placed boda boda operators at the heart of his Bottom-Up Transformation Agenda (BETA), which seeks to dignify jua kali jobs as part of his job creation plan.

Motorcycles were the fastest growing mode of transport, with the Treasury estimating that two and three-wheelers accounted for the largest share of the national fleet at 67 percent.

Then things started to unravel. A combination of factors, including a difficult macroeconomic environment due to high fuel prices and interest rates, made it difficult for some of the borrowers to repay their loans.

The boda boda market became saturated as it attracted many people and outstripped available demand.

One of the largest motorcycle lenders, Watu Credit, said that more than half of the boda boda operators were struggling to service the loans they took out to buy the two-wheelers.

The micro-lender said that over fifty percent of its active customers had "huge arrears", forcing the company to reschedule most of the loans.

Also, due to the tough economic times, some of the boda boda operators have managed to find ways of disconnecting the tracking system to avoid paying loans, said Kitui Central Police OCPD Peter Karanja.

“There is a tracking system which they will immobilise and then come and claim that the motorcycle has been stolen. So, it is like they want to get away with it and fail to pay,” said Karanja, whose police station has dealt with several such cases of motorcycle theft.

Microlenders have been aggressively pursuing defaulters, using extreme collection methods that have caused a storm.

Those who failed to pay their loans lost their motorcycles, some after paying up to 90 percent of the loans, according to a petition to the National Assembly's Finance and National Planning Committee.

The petition to the committee was submitted by Kigumo MP Kamau Munyoro, who accused five micro-lenders of predatory lending practices that saw some of the motorcyclists paying as much as Sh500,000 for the bikes. The committee's chairperson, Molo MP Kimani Kuria, said they were yet to adopt the report, although there is a recommendation to amend the Central Bank of Kenya Act to bring the Buy Now Pay Later (BNPL) products under the regulatory purview of the financial regulator.

The motorcycles on loan are usually fitted with a tracker using GPS technology. Someone from the lending company tracks the whereabouts of the motorcycle to prevent theft.

Most of the riders we spoke to said that the theft of these motorcycles occurs just as they are about to finish paying their loans, or after they have finished paying, which is why some of them suspect that the motorcycle thefts are orchestrated from within the lending companies. The lending companies have denied the allegations.

Allan Musembi, chairman of the Machakos Town Boda Boda Association, while absolving the lending companies of blame, insisted that their employees may have been involved in the theft of the motorcycles.

Firstly, Musembi said, even after the riders had finished paying off the loans, they were never asked to bring the motorcycles to have the tracker disconnected, as ownership of the motorcycle was transferred to the boda boda operator.

Secondly, at their peak, most of these lending companies were overstaffed as they rode the wave of good business where motorcycles were flying out of their godowns like hot cakes.

But when business slowed down, most of these micro-lenders were forced to lay off a lot of staff, many of whom, Musembi argues, could still be watching the bikes and colluding with the thieves.

“Even now, if I was to call any employee of the lending companies and ask them to look for details on any motorcycle, they will get it for me, regardless of where they are,” said Musembi.

“I think all these people have access to the motorcycles. There was no adequate privacy of property.”

Ken Onyango, chairman of the Kenya National Boda Boda Association, noted that because the rental companies have a tracking system, it is their primary responsibility to report any theft to the police.

“However, these companies dilly-dally. And by the time they are taking action, the motorcycle is either on the border or the tracker has already been disabled,” adds Onyango.

Martin Mutua, a security person who helps one of the firms to recover stolen motorcycles, has a different opinion.

According to him, it is the boda boda operators who have enabled the theft by boasting to their colleagues when they are about to pay off their loans.

“This boasting is what sends a signal to the other boda boda operators,” said Mutua, noting that some of the operators have ill motives.

“Some of them (boda boda operators) are thieves. And they are the ones giving away their friends.”

According to Mutua, the moment a rider finishes paying his loan, the tracker is disconnected by the company as the logbook is transferred to the boda boda operator.

“Then you come to tell a friend that you have finished paying for the motorbike. They take advantage, knowing that this motorcycle has no tracker, so even if they steal it, there is no way of finding it easily,” added Mutua.

The stolen bikes are first dismantled into parts and their engines are used to make speedboats, water pumps and generators, according to the authorities.

Muthiani says that when they arrived at the Kenya-Tanzania border at Loitokitok, they were allowed to cross the border where they saw the godown where most of the stolen motorcycles ended up. It was a three-storey building, fenced in and with an open-door policy. Its owner, they were told, was well connected.

“If the government helps us to deal with the guy receiving the motorbikes we will solve this mystery. But as long as the guy is there, the kids will continue being killed.”