Time for a constitutional review? Rethinking affirmative action and gender diversity

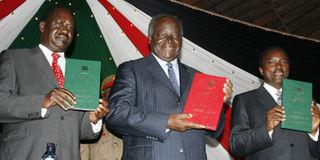

Former President Mwai Kibaki (centre), Prime Minister Raila Odinga and Vice President Kalonzo Musyoka hold the Constitution at KICC, Nairobi.

What you need to know:

- The Constitution of Kenya 2010 guarantees gender equality through the Bill of Rights, affirmative action, and the two-thirds gender principle.

- However, weak implementation and resistance undermine these protections.

This season marks the 15th anniversary of the Constitution, a good reason to assess its guarantees on gender equality and the debates surrounding them.

In the Bill of Rights, the Constitution provides that women and men have the right to equal treatment and opportunities in political, economic, cultural and social spheres. It restrains the State or any other entity from discriminating on any ground, including sex, pregnancy, marital status and dress.

It further requires the State to take legislative and other measures, including affirmative action, to redress any disadvantage suffered because of past discrimination. The Constitution categorically states that not more than two-thirds of members of elective or appointive bodies shall be of the same gender.

The extent to which this has been observed varies. Most noticeable is the tendency to interpret the provision conservatively—that women must occupy the one third. This minimisation entrenches tokenism. A faithful application would also produce cases where men are the minority, yet such examples are rare.

Resistance is also evident in the fact that Parliament has yet to enact a law to give effect to this principle. Contempt for the provision was clear when the Supreme Court issued an advisory setting a deadline for compliance, which was simply ignored without consequence.

One of the major gains of the Constitution was the creation of 47 county woman representative positions, guaranteeing a minimum number of women in the National Assembly. Critics consider this position superfluous, a waste of public resources and a duplication of the role of constituency Members of Parliament (MPs). The criticism could be reduced if the lawmakers performed impressively. In fact, many women representatives have been recognised among the most active legislators.

It is tacitly understood that the post is a platform for women to enter politics, gain experience and move on to other competitive positions. This has happened to some extent. Gladys Wanga, governor of Homa Bay, started off as a woman representative. So did Rozaah Buyu, current MP for Kisumu West.

Some observers argue that the terms should be limited so that one person does not seek the same post indefinitely. They invoke the principle of a “sunset clause”—that affirmative action should expire after a prescribed period to avoid breeding complacency and entitlement.

Supporters of the woman rep position point out that through the National Government Affirmative Action Fund, many community-level projects have been implemented to the benefit of disadvantaged and marginalised groups. Critics, however, view this as a distortion of the duties of an MP. As argued in legal circles, it is not the responsibility of legislators to manage funds and implement projects.

Gender laws

Riding on the promulgation of the Constitution, several laws addressing gender issues were passed. These include the Prohibition of Female Genital Mutilation Act, 2011, which criminalises actions that promote the practice; the Kenya Citizenship and Immigration Act, 2011, which protects married women from losing their citizenship upon marriage to foreigners; the Matrimonial Property Act, 2013, which accords spouses equal rights on acquisition, administration, control, use and disposal of marital property; the Marriage Act, 2014, which declares that parties to a marriage have equal rights at all times; and the Protection against Domestic Violence Act, 2015, which provides relief for victims of domestic violence but is more administrative than penal.

The constitutional provision that parties to a marriage are entitled to equal rights at the time of the union, during its subsistence and at its dissolution continues to be tested in courts of law. It should continue to be debated and read critically.

For instance, to the extent that the Marriage Act allows men to marry more than one wife under customary and Islamic law, can it truly be said to uphold equality—or does it contravene it?

The Constitution also entrenches the right of both male and female offspring to an equal share of ancestral property. Yet patriarchal cultural practices continue to favour males, though change is increasingly observable.

If the Constitution were a human being, it would now be in puberty, a stage that requires careful management to prevent maladjustment. In the same way, the time is ripe for a review of the document.

Key gender issues for re-examination include: realising gender balance in the legislature; reconfiguring or abolishing the woman rep position in favour of other mechanisms; defining the duration of affirmative action; and embracing diversity more fully, particularly by recognising intersex and transgender persons.

The writer is a lecturer in Gender and Development Studies at South Eastern Kenya University ([email protected]).