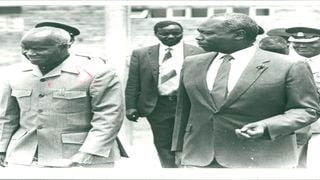

President Moi escorts President Kenneth Kaunda of Zambia to his plane at the JKIA on October 1, 1987.

| File | Nation Media GroupNews

Premium

Kenya’s superb role in the Pan-African movement

What you need to know:

- Today, Kenya is still leading in efforts to demilitarise civilian populations in the Democratic Republic of Congo and in confronting the al-Shabaab headache in neighbouring Somalia.

- Kenya was thrown into negotiating conflicts in Africa during the Cold War. Jomo Kenyatta found himself in 1975 resolving the Angola crisis between Unita leader Jonas Savimbi, Holden Roberto of FNLA, and Agostinho Neto.

Kenya has never had a bigger galaxy of pan-Africanists than the political team of the 1960s. In this mix were Jomo Kenyatta, Pio Gama Pinto, Mbiyu Koinange, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga, Tom Mboya and Joseph Murumbi. Their politics transcended the nation, and Kenya was turned into a space where pan-African politics thrived.

In continental politics – whether lobbying on the formation of the Organisation of African Unity or non-alignment membership – you could always count on these internationally respected super-diplomats. They could easily find coverage in international media, for their statements carried the thinking of other silent African politicos.

Today, Kenya is still leading in efforts to demilitarise civilian populations in the Democratic Republic of Congo and in confronting the al-Shabaab headache in neighbouring Somalia – an indicator of its continued presence in Africa’s theatres of war. It has been a long walk. From the late 1950s, when Ghana became the first colonised African nation to gain independence, one of the goals of pan-Africanists was the retention of the colonial maps – to evade the chaotic cartography that could have befallen African countries as they entered the post-colonial phase.

President Jomo Kenyatta with United Nations Secretary-General Kurt Waldhelm at State House, Nakuru, on May 8, 1976.

Kenya was unlucky, too. The country started with a national headache after the expansionist Somali government engineered some nationalist claims on Kenya’s ‘northern frontier districts’ of Mandera, Wajir, Garissa and Moyale. They also claimed the Ogaden region of Ethiopia.

This irredentist move would lead to prolonged civil strife in that part of Kenya.

Another poser facing Africa at the dawn of independence was what to do with alternative races. A multi-racial Africa seemed to create a dilemma in some countries – especially with white settler societies. Kenya was at the forefront of imagining a multi-racial state in theory. In November 1963, pan-Africanists Mboya and Odinga attacked a group of backbenchers who lobbied the House to refuse Kenya citizenship to anyone who was not a black African.

Multi-racial state

Mboya’s and Odinga’s stand sent signals across Africa that Kenya would build a multi-racial state. In Parliament, Mboya questioned why members were comfortable attacking racism in South Africa, the United States and Portugal and still thought it was “morally right to discriminate against people” based on their skin colour.

This paradox emerged during the discussion on the Citizenship Bill after MPs Oduya Oprong and Gideon Mutiso asked Parliament to restrict citizenship, jobs, and businesses to blacks only. So Kenya knew it had to lead from the front. Internationally, Kenya was pursuing a non-aligned, pan-African foreign policy combined with Commonwealth membership.

But while there was a stated claim of neutrality, the reality was that Kenya was leaning more towards the West than the East, reflecting the views of Kenyatta and Mboya and the realities of development aid and finance.

As a result, Kenya’s foreign policy reflected the tensions between its non-alignment policies and the domestic pressure to support self-rule for the then-colonised, white-ruled African states. The pressure was from some donors pushing African nations to support their Western interests.

Within Africa, Kenya was asked by the Organisation of African Unity to lead peace negotiations in the 1964 Congo crisis. This crisis followed the US-backed murder of Patrice Lumumba in 1961. In 1964, a pro-Lumumba communist-backed rebellion captured large areas of the country and took hundreds of foreign hostages.

The US-supported prime minister, Moise Tshombe, responded with white mercenary-led troops as both East and West armed their proxies. While the OAU asked Kenyatta to mediate and the Americans attended talks in Nairobi in 1964, Kenyatta was furious at the US deception, and some anti-US demonstrations took place in Nairobi. Kenyatta’s anger was after the US assisted Belgian paratroops in rescuing the hostages, killing many Congolese while he was negotiating. He had learned his lesson.

There were challenges in East Africa too. While Kenya and Uganda were dragging their feet towards an East African federation, Tanganyika’s Julius Nyerere reached out to Zanzibar, a country on its own, and they decided to form the Republic of Tanzania on April 27.

Kenyatta and Obote felt slighted by Nyerere after they learned that Sheikh Abeid Karume and Nyerere had exchanged Articles of Union – and only got to know after the deal was inked. As a result, the idea of an East African Federation hatched in the run-up to independence did not materialise. Instead, it was the East African Community that would be formed.

But the EAC started limping in 1971 after Idi Amin deposed Uganda’s President Milton Obote in a military coup. After that, Kenyatta and Nyerere decided to cold-shoulder the new Uganda president, with Nyerere vowing never to sit down with Amin. As a result, the East African Authority, the highest organ within the EAC and which brought together the three presidents, did not meet after 1971.

This falling-out was driven partly by ideological differences and partly by ego. While Kenya and Uganda had rejected nationalisation of foreign companies – at least by the time the EAC was formed – Tanzania embraced socialist principles. Nyerere thought of Kenya as a neo-capitalist “man-eat-man” society. Kenyatta thought Idi Amin was a “mad man”, their relationship was further complicated by Uganda’s claim of some parts of Kenya.

On the positive side, Kenya was thrown into negotiating conflicts in Africa during the Cold War. Jomo Kenyatta found himself in 1975 resolving the Angola crisis between Unita leader Jonas Savimbi, Holden Roberto of FNLA, and Agostinho Neto. In the crisis, the Eastern bloc had backed Neto, while the Western bloc supported Roberto and Savimbi. Kenyatta told the leaders that the Angola crisis was an “imperial game of divide and rule”.

Africa was the playground as the ideological rift between East and West translated to a bitter contest over Africa, with each bloc trying to broaden its turf. For instance, the Soviet Union – since it had no colony – was trying to get a foothold in various parts of Africa.

The collapse of the East African Community on its tenth birthday and the closure of the Arusha offices created a bitter divide between Kenya, Uganda (under Idi Amin) and Tanzania. As a result, Tanzania closed its border with Kenya in February 1977 and all three countries seized EAC assets on their soil.

By lobbying the UN to establish a UNEP headquarters in Nairobi, which opened in 1972, Kenyan diplomats surprised many due to their compelling presentation. Nairobi was a source of pride for the Global South, for it was the only UN headquarters outside the Global North. Apart from the UN headquarters, the other offices were in Vienna and Geneva.

President Daniel Moi (left) bids farewell to President Nyerere of Tanzania at Jomo Kenyatta International Airport.

Another significant contribution was when Moi was Chairman of the Organisation of African Unity from 1981 until 1983. He was the only Chairman who served for two terms, for OAU members could not agree on the chairmanship of Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi. Therefore, the Libya Summit could not raise a quorum. While Moi was Chairman, the question of Polisario and Morocco arose. More crises would follow after OAU Secretary-General Edem Kodjo admitted the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic to an OAU Ministerial meeting in Addis Ababa. This invitation produced a split in the organisation over the legality of his action. As a result, Morocco led a boycott of the OAU. Finally, in June 1981, chaired by Moi, the Summit agreed on the Western Sahara referendum and ceasefire.

Kenya has been contributing its troops to African causes. For example, during the Namibia transition to a free state, Kenyan troops under Daniel Opande were deployed in 1989 under the United Nations Transition Assistance Group. This would see Kenya contribute troops to other regions such as Liberia, Sierra Leone, Somalia and Sudan.

Kenya’s invasion of Somalia in October 2011 to destabilise al-Shabaab bases caught the world’s attention. It was the first time that Kenyan troops had invaded another country. The troops have been integrated into the African Union Transition Mission in Somalia – the final phase of the peacekeeping force before foreign troops are withdrawn from Somalia by December 2024.

Peace Agreement

Kenya has also played a role in stabilising the region and led the international effort to create the new state of South Sudan. It was in Kenya that a final Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) was signed in 2005 to mark the end of the long-running, 22-year-old, civil war in the Sudan. Besides Sudan, Kenya was involved in negotiating with the various factions in Somalia, and Nairobi was turned into a hub as the Transition Authority was born.

For the last 60 years, Kenya’s imprint in Africa’s crisis has been a mixed bag of success. While it was part of the group that sabotaged the initial Kwameh Nkrumah dream of a united Africa, it was also instrumental in forming the OAU and its successor, the African Union. Moreover, it is widely regarded as a diplomatic powerhouse and respected within the UN.

It has been 60 years of pan-Africanism, twists and turns.

[email protected] @johnkamau1