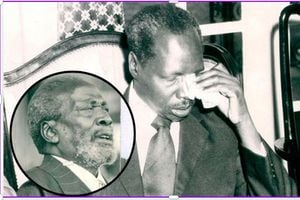

President Daniel Arap Moi confers with the then Kanu chairman Peter Oloo Aringo during a meeting at Afraha Stadium, Nakuru.

In his prime, Peter Castro Oloo Aringo was the ultimate Kanu loyalist, strutting about with President Daniel Moi’s lapel pin like it was a badge of honour.

No one doubted where his loyalties lay. Back in 1969, fresh out of the University of Nairobi with a first-class honours degree in history, Oloo PC was top of his class and primed for greatness. He was a bright spark, an academic high-flyer with a flair for political theory, particularly the Machiavellian kind.

Naturally, he took to Kanu like a fish to water, cheering on the regime with the zeal of a true devotee.

But as with many political stars, his shine didn’t last. Once the Kanu glory days faded, so did he, drifting quietly into obscurity, his Moi pin likely tucked away in a drawer, a relic of an era that had passed him by.

The 83 year old Aringo who died on Friday, November 1, 2024 was a keen reader of Niccolò Machiavelli and thrived in the doctrine: the end justifies the means, even if those means veer into the morally murky. It made him a perfect fit for Kanu during its rockiest years, as he became the party’s most vocal cheerleader, unfazed by its controversies.

Aringo’s loyalty to the party was so unabashed that Bishop Henry Okullu dismissed him as a “court poet and master of platitudes.”

He, without battling an eyelid, cheered the detention without trial of Kenneth Matiba and Charles Rubia for advocating the introduction of multi-party democracy.

Aringo's entry into politics was more than just ideological zeal — it was also family. His ties with the powerful Odinga dynasty, courtesy of his marriage to Jaramogi Oginga Odinga’s daughter, offered him an influential platform in Nyanza’s political theatre.

He was among those who aimed to unseat anti-Jaramogi forces in the region, and it was smooth sailing. Aringo won the Alego-Usonga seat in 1974, holding on with enviable persistence until 1992 and later snagging another term from 1997 to 2002. For years, he embodied leftist politics — until the momentum started waning in 1988.

So connected was Aringo to the Odinga family that, in 1977, he joined a covert delegation to meet with Mbiyu Koinange, Minister of State, seeking reconciliation between Jaramogi and President Jomo Kenyatta. Though this hush-hush mission stayed off the public record, Aringo couldn’t resist sharing the scoop with US Embassy officials, who obligingly leaked it to Washington. We now know of the meeting, thanks to US archives.

Born in 1941, Peter Castro Oloo Aringo’s path to politics was paved with elite schooling and early career ambition. He started at St Mary’s Yala — alma mater of many Nyanza bigwigs — and trained as a teacher at Siriba College in Maseno from 1961 to 1962. He returned to teach at his old school in 1963, but soon sought a change of scenery — first at Kapsabet Secondary School, where he taught until 1966, then off to the University of Nairobi for a degree.

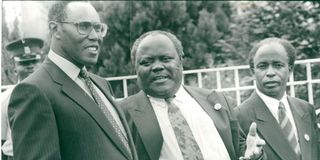

The then Vice President George Saitoti (left) with Oloo Aringo (Minister for Manpower Development and Employment) and Joseph Kamotho (Minister for Education).

With a bachelor’s degree in hand, Aringo wasn’t done yet — he headed to the University of Toronto for a Master of Arts in African politics, a subject he lectured on briefly before heeding the call of home in 1971. Back in Kenya, he taught at Aquinas High School and Upper Hill before moving up as Vice Principal at Kenya Polytechnic in 1973. Ever the multitasker, he also enrolled in a PhD programme at the University of Nairobi.

But academia was only a pit stop. When the 1974 elections loomed, the lure of politics was too tempting. Leveraging his teaching network and connections with local influencers, he launched a campaign, backed by the Odinga family’s powerful influence and his friendship with Ambrose Adongo, the Kenya National Union of Teachers Siaya Branch Chairman.

Jaramogi Oginga Odinga's endorsement was Aringo's magic ticket, propelling him to a landslide victory with 12,980 votes against Dr Zachary Nyamodi’s 2,900. In one candid interview, Aringo acknowledged Jaramogi's role: “Jaramogi threw his weight behind me when I went to get his blessings."

At just 33, Aringo joined Parliament, bringing fresh energy and a proudly leftist outlook. He found himself among a bold assembly of like-minded firebrands — including George Anyona, Onyango Midika, Martin Shikuku, Chelagat Mutai, and Elijah Mwangale. But the 1975 tragic death of JM Kariuki, a fierce critic of the Kenyatta government, shook this crew, underscoring the risks of challenging the political status quo.

Aringo took on the role of Parliament’s resident crusader for the detained and the exiled, sparing no effort in challenging the government over the Kenya People's Union detainees. His most memorable battle was fighting for the release of the ailing Wasonga Sijeyo, one of Mzee Kenyatta’s longest serving detainees.

In 1979, Aringo turned his focus to another ex-detainee, the renowned Prof Ngugi wa Thiong'o, boldly raising the question: "Why has Prof Ngugi wa Thiong'o not been reinstated to his position at the University of Nairobi, despite requests from students, staff, and Kenyans who value his contributions to our African cultural heritage?"

The the Minister for Energy Nicholas Biwott (left) with Oloo Aringo (Minister for Education).

Assistant Minister for Education Maina Wanjigi danced around the issue, vaguely referring to a “misunderstanding” between Ngugi and the university. But Aringo saw through it, worried Kenya might lose the acclaimed writer to exile. With characteristic bluntness, he demanded, "Can the Assistant Minister ensure that people like Prof Ngugi, of world prominence and vital to our country, aren’t forced to spend their lives in exile?"

By being pro-people, Aringo held tight to the Alego seat until 1992, when he lost the seat. By 1997, he staged a comeback, slipping back into his old role as if he’d never left. But in 2002, the tides turned — he was swept out of office by the younger, more energetic Sammy Weya. And with that, Aringo’s political journey hit its final stop.

Back in Parliament, Aringo set his sights on shaking things up, pushing for both parliamentary independence and a Truth and Reconciliation process. While his call for reconciliation didn’t gain traction at the time, it set the stage for what would later become essential after the post-election violence of 2007.

In 1999, Aringo scored a major win for parliamentary independence by moving a private member's Bill that created the Parliamentary Service Commission, cementing Parliament’s supremacy. It was one of his lasting legacies — a nod to his vision of an empowered legislature unafraid to stand on its own two feet.

In 1979, Aringo was among those swept up in Moi's political charm offensive aimed at welcoming Kenya People’s Union leader Jaramogi Oginga Odinga and his allies back into the fold. As Moi hunted for new friends in the Nyanza region, Jaramogi was appointed chairman of the Cotton Lint and Seed Marketing Board, and allies like Achieng Oneko and Luke Obok were given key roles in parastatals. For Aringo, though, the real shift came in 1980, when he joined Moi’s Cabinet, trading his leftist ideals for a Kanu loyalty badge.

The moment happened one evening at Moi's Kabarak home, where Aringo and his wife, Edidis, were invited for a casual political tête-à-tête over dinner. Moi, hinting with a statesman’s subtlety, remarked, "As you can see, my Cabinet is full. But if you behave, I’ll consider you in the near future."

Later, Aringo revealed Moi’s friendly "advice," aimed right at his scruffy beard and that rebellious middle name, Castro. “Moi told my wife he’d like to work with me but didn’t like my beard — or my middle name!” Back home, Aringo promptly shaved, smoothed out his edges, and agreed to "behave" just as Moi had requested. And just like that, a new Moi loyalist was born.

Aringo quickly found himself charmed by the perks of Nyayo’s inner circle. Hezekiah Oyugi, the influential Rift Valley Provincial Commissioner — and later Internal Security Permanent Secretary — orchestrated his induction into Moi’s elite club, a transition sealed with that fateful dinner at Kabarak.

After dutifully complying with Moi’s advice to shave, Aringo returned to Nairobi feeling freshly reformed. Just as he was getting comfortable, a lunchtime news bulletin on KBC announced his appointment as Assistant Minister for Higher Education under Prof Jonathan Ng’eno.

It was official: Aringo had shed his beard, and Nyayo had taken note. By then, beards had become bold symbols of defiance, much to the chagrin of the establishment. Attorney General Charles Njonjo famously scoffed at Moi’s critics, dubbing them “bearded sisters.”

Aringo, for his part, embraced the symbolism — until it clashed with ambition. In one 1979 exchange in Parliament, when he posed a question to the Assistant Minister for Lands, G.G. Kariuki, Kariuki retorted, “Shave your beard first!” Unfazed, Aringo shot back, “The Assistant Minister suggests I shave, but I have some fertiliser he might borrow to improve his own!”

Part 2 in Nation Africa and the Daily Nation: ‘How Moi groomed Aringo to power’