Premium

Lee Njiru recalls day minister accused Mama Ngina of plotting to eliminate Moi

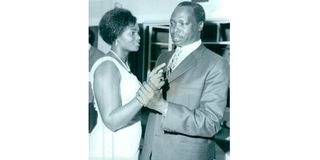

Former president Daniel arap Moi and Mama Ngina.

What you need to know:

- As a teetotaller, President Moi could not stand the State House Comptroller, Gitau, an alcoholic.

- One morning, Ng’eny arrived in his office and asked Ameda to bring him his daily dose of vodka and tonic water.

For 24 years, President Daniel arap Moi’s State House was a theatre of intrigues and drama as influential individuals rose or fell jostling for power and favours. In this second instalment of an exclusive four-part serialiasation of an ultimate insider’s tell-all book revealing the deepest secrets of the Jomo Kenyatta and Moi governments, Lee Njiru writes about a purge, paranoia and politics in his memoir, Presidents’ Pressman. Here is the gripping story of the plan to kick-out disloyal Kenyatta-era power men and how the new president’s mistrust after the 1982 coup attempt was a magnet for fraudsters bearing Shakespearean treachery plots with imaginary enemies — including one incredibly claiming that the former First Lady was training sharpshooters in a forest to target the Head of State

When (President Daniel) Moi ascended to power (in 1978 after the death of Jomo Kenyatta), I feared for people like (Isaiah) Mathenge, (Geoffrey) Kariithi and (Bernard) Hinga. Early in 1977, vice-president Moi had, during a meeting in Machakos, called for reorganisation of Kenya’s taxation, saying it was punitive and was driving young entrepreneurs out of business. Kariithi (the Head of Civil Service) came out guns blazing. He issued a stinging statement blasting Moi for his views but Moi kept silent. He knew the best option was to bide his time.

Now, after becoming President, Moi summoned me to the Office of the Comptroller. He asked me to sit down over a cup of tea. After a few minutes, Kariithi was ushered in by security officers. Moi had a letter ‘written by Kariithi’ asking the Head of State to allow him to retire. Kariithi did not know anything about the letter. When Moi placed the letter in front of Kariithi, he tried to protest. “Sign here,” Moi ordered.

A frightened Kariithi signed himself out of office. Moi then told me to announce the ‘voluntary’ retirement of Kariithi and the appointment of Jeremiah Gitau Kiereini, a Charles Njonjo ally, to succeed him. Police Commissioner Hinga, was treated in a similar manner. Both were not allowed to leave State House until the news bulletins were broadcast over the VoK (Voice of Kenya). The broadcasts were aired immediately. We had a radio set in the office. The victims also heard the news together with us.

The news item went thus, “Reports reaching us from State House, Nairobi, say that His Excellency President Daniel arap Moi has accepted the retirement request by the Head of Civil Service, Geoffrey Kariithi. Consequently, the President has appointed Jeremiah Gitau Kiereini to be the new Head of Civil Service and Secretary to the Cabinet.”

Right: Head of Presidential Press Unit, Mr Lee Njiru, contributes Sh185,000 during a harambee in aid of Moi High School, Mbiruri in the 1990s.

Hinga was replaced by the GSU Commandant, Ben Gethi (as police commissioner). Interestingly, Rift Valley PC (provincial commissioner), Mathenge, survived by dint of his close relations to the Kenyatta family. Moi allowed him to stay until he retired in 1980. He was succeeded by Arthur Njuguna Ndoro who believed that Moi was a passing cloud. Ndoro was removed in 1981.

***

As a teetotaller, President Moi could not stand the State House Comptroller, Gitau, an alcoholic. Gitau actually accelerated his removal from State House. Instead of realising that Moi loathed alcohol, or excessive use of it, Gitau continued with his old bad habits. He actually increased the rate of his drinking sprees. And he became careless with his tongue.

One day, Mzee Moi was being entertained by choirs and traditional dancers at State House, Nakuru. The entertainment arena was full to capacity. Then the unthinkable happened. Gitau walked across the arena and in front of the presidential dais where Mzee Moi sat with other VIPs.

“You have banned corruption. That’s OK. Where do you expect public officers to get money to contribute to your harambee projects?” he asked Moi as he staggered across the floor. Moi did not answer him, but security officers escorted him out of the arena. That was the last question he asked Mzee Moi. He was lucky that Moi deployed him in government instead of summary dismissal.

He was replaced by Andrew Limo arap Ng’eny, who had worked in the Ministry of Agriculture with Cabinet minister Nicholas Biwott. It was believed that he was Biwott’s protégé. What Moi did not know was that the new comptroller was also an alcoholic.

President Kenyatta and Mama Ngina during New Year celebrations in the 1970s at State House, Mombasa

One of Ng’eny’s first undertakings was to set up a secret bar on one side of the upper floor of State House, Nairobi. Moi knew nothing about this establishment. As soon as Moi left the office in the evenings for his Kabarnet Gardens residence, Ng’eny would call the Nairobi PC (provincial commissioner) Paul Boit, and the managing director of the Kenya Posts and Telecommunications Corporation, Kipng’eno arap Ng’eny. The three would drink until 10pm and then move to the United Kenya Club where they caroused till midnight. This became a daily routine whenever Moi was in Nairobi.

Ng’eny’s day started with a glass of double vodka mixed with tonic water. This was dutifully served by a man called Ameda, an expert in mixing alcoholic drinks. He had been inherited by Mzee Jomo Kenyatta from the last colonial governor, Sir Patrick Reneson. Ameda always carried a cherished bottle opener with the British Coat of Arms embossed on it.

One morning, Ng’eny arrived in his office and asked Ameda to bring him his daily dose of vodka and tonic water. As soon as he made the order, he left the office and went to the washroom. Mzee Moi entered Ng’eny’s office and ordered a glass of water from another waiter. Before the waiter came back, Ameda entered carrying Ng’eny’s vodka. Mzee Moi thought it was his water, and stretched his arm to take it. In the nick of time, Ng’eny entered and snatched it from Ameda. It was then that the waiter with the glass of water arrived and gave it to Mzee Moi. The President noticed something and rebuked Ng’eny thus “wewe nyang’au”, meaning “you hyena”. It was such a terrible embarrassment for the new comptroller.

Mr Geoffrey Kariithi, the former Head of Civil Service, who President Moi forced to resign after taking over power from Jomo Kenyatta in 1978.

Ng’eny unfortunately died in a road accident in 1983 near the Stem Hotel in Nakuru. His death had a curious element. Whenever he wrote a note to somebody, he signed it ‘ALAN’, short for Andrew Limo arap Ng’eny. The driver of the lorry which Ng’eny’s car rammed into was called Alan Kamau.

**

Ministers who conned Moi

The attempted coup (on August 1, 1982), and the fear it visited upon President Moi, became a cash-cow for greedy individuals who knew how to work the levers of fear. Most of them were super conmen. They studied the presidency and identified Moi’s closest friends. They isolated those who had limited capacity for analysing and interrogating falsehoods and especially when presented by smartly dressed fellows driving flashy cars.

Among the innocent friends of President Moi were Ezekiel Birech (the Bishop of the African Inland Church), Davidson Ngibuini Kuguru (the Minister for Home Affairs) and Timothy Mibei (the Minister for Public Works). I remember Minister Kuguru bringing to State House a man who had lied to him that he had been part of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) military force that had killed President Juvenal Habyarimana in 1994. This ‘RPF man’ cheated Moi that President Yoweri Museveni of Uganda had deployed a large number of troops in Mount Elgon with plans to invade Kenya.

Moi was very agitated. His escort commanders, Elijah Sumbeiywo and Charles Kimurgor, were always on the firing line “for having no clue about these evil plans”. President Moi at one time told me that he was losing faith in his intelligence officers. “Tutashikwa kama kuku!” he exclaimed, meaning, “we shall be captured easily like chicken”. This conman left State House with a briefcase full of money.

Moi later told me the fellow had also fought alongside the late Fred Rwigema (a legendary Rwandan military officer and politician who founded RPF). He had showed Moi his photographs wearing camouflage military fatigues and toting a general purpose machine gun. All these combat uniforms had been sourced from friends in the military. Bishop Birech was a highly religious, simple and forthright individual.

He was honest and loved Moi to a fault. If a conman approached him with tales about schemes of harming Moi, he would obviously be alarmed. The conman would ask him to arrange for a secret meeting with Moi. And Moi would never say no to Birech, his spiritual leader. The Director of Criminal Investigations, Noah arap Too, told me how Moi would telephone him with a trembling voice, accusing him and the Directorate of Intelligence for sleeping on the job when Kenya was about to be invaded.

Somebody had, through Timothy Mibei, who at one time served as a magistrate, Public Works Minister and MP Bureti Constituency, informed Moi that heavily armed assassins were on the prowl in a red car. Whenever we travelled, everyone in the motorcade, including the security, the Press, the valets and other domestic staff were instructed to be on the lookout for any red car coming towards or following us. We always lived in fear. But what was most disgusting was that certain politicians, including ministers, connived with conmen to extort money from Moi.

A Cabinet minister from Kiambu, who presented himself as rich and stylish, made malicious allegations against Mama Ngina Kenyatta. He told Moi that the former First Lady was training a team of assassins in a forest in Athi River. He said they were practising with sniper rifles using pumpkins as targets. When Moi narrated this story to me, I jumped off my seat.

“Your Excellency, that is impossible. There is no forest in Athi River. The army uses this area as their rifle range. Mama Ngina cannot do that. Your minister is out of his mind,” I told Moi. I promised to send a senior television cameraman from the PPS (Presidential Press Service), which I headed, to comb Athi River and unearth the truth. Moi agreed. We settled on Ernest Kerich, who later became the head of the Film Department. Kerich scoured every area mentioned by the offending minister but there was no such thing.

I convinced Moi to overfly the Athi River area and see for himself that there was no forest where assassins could practise as alleged without being noticed. We flew to Kathiani via Athi River in an Air Force helicopter, keeping as low as possible so that President Moi could make his own judgment. “Terrible, terrible,” Moi commented, showing obvious disgust.

The problem was that he was not willing, for political reasons, to discipline his minister who was immensely influential in Kiambu politics. He just ignored him. From then on, he held him (the minister) in utter contempt. Then there was another influential minister from Nyanza who at one time held the Foreign Affairs portfolio. He began capitalising on the fact that most of the planners of the 1982 abortive coup were soldiers from his tribe.

He assembled a group of about 30 young men whom he had coached to cheat the President that they were part of a larger group of angry former Air Force officers who were planning to undertake a bloody revolution in the country. He told the President the young men had abandoned their plans and were now fully behind Moi’s leadership. When I looked at those people, it was obvious most of them had no knowledge of military warfare. They were clumsy, devoid of any military poise or demeanour. I looked at them more closely, and listened to them more attentively. Moi was being conned in broad daylight. And by his own minister. I wondered why the then Presidential Escort Commander, being a military man, could not discern the deception in their presentations.

I even suspected that maybe he was part of the wider scheme to con Moi. Things changed when a new Presidential Escort Commander, Stanley Kiptum Manyinya, took over. He was posted from the elite Recce Company. When he reported, I told him about my reservations regarding these delegations conveying frightening tales and the colossal amounts of money dished out by the President in return. Manyinya and I approached the President and begged him to give us an audience. Moi agreed. I broke the ice.

The President shifted his weight, chin in his right hand. I told him, blow by blow, about the continual lies by his trusted friends. As he listened attentively, I became bolder. I was prepared for any backlash. As they say in Swahili, ‘kama ni mbaya ni mbaya’ that loosely means “I’m ready to face the consequences”. When I was through, Manyinya reiterated what I said, colouring it with military perspectives to great effect. “So, what are we supposed to do?” Moi asked us, his tone betraying a sense of frustration.

Manyinya told him that anybody brought to him claiming to have been a military combatant, in Kenya or elsewhere, should be tested on small arms handling, which is stripping, cleaning and re-assembling. These are the basic skills taught to military and police recruits all over the world. And it came to pass.

One day, a Cabinet minister from Kericho booked an appointment to see the President. He came with a group of young men claiming to have undergone guerilla training in Libya. The same young men claimed that the President of a neighbouring country was planning to invade Kenya and that they had been recruited to offer critical information about their country. President Moi passed this information to me and Manyinya.

Early in the morning, before the young men were presented to the President, we assembled various types of rifles and pistols, placed them on a long table near The Retreat, a building in the bush within State House grounds. This is where Moi used to retreat and unwind, eat goat meat with close friends while reviewing political issues and gossip across the country.

Some of the guns we placed on the table were AK 47, G3, General purpose machine guns, FN, Israeli Uzi and Galil, Ceska, Beretta and Smith and Wesson pistols. The conmen who came to see Moi were five. They were ushered into the waiting room together with the politician who was leading them. Moi, as earlier agreed, asked Manyinya to process them. Manyinya asked the conmen to follow him to The Retreat. They recounted to Manyinya their exploits in Libya and Uganda. They even showed us their photographs donning military fatigues and toting machine guns. Manyinya was heavily built.

He was right-handed but used his left fist devastatingly. One by one, he called each of the young men aside. “Pick the gun you are comfortable with, strip it and reassemble, and explain how it is used,” he instructed. None of them understood any of the guns. One said he had been a cook, another had worked in a laundry. They all received Manyinya’s punches. One of them was floored. Another one spat blood. They could not run away as they were surrounded by presidential security officers. Later they were allowed to leave, their heads hanging in shame.

The politician who had brought them also left the State House terribly embarrassed. This measure by Manyinya reduced the incidents of politicians and gullible friends of Moi bringing conmen to instil fear and fleece the President.

But there was another man, a former mayor of Nyeri town, who contrived a different trick. He contracted some jua-kali artisans to fabricate rifles, and other weapons. Every week he would bring one, claiming it had been surrendered by converted criminals who had vowed to work for Moi and protect him at all costs. Manyinya unmasked this conman, stopping his shenanigans once and for all. © Lee Njiru 2022

Tomorrow in the Daily Nation: Why Moi chose Uhuru as his successor.