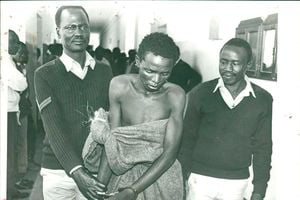

Kamukunji MP Yusuf Hassan.

What they don’t know is that behind the benign face, is a fierce political agitator and civil rights activist who was once a thorn in the flesh of President Daniel Moi’s regime during the Second Liberation.

Perhaps what Yusuf himself might also not know was that his political activities did not only place him on the radar of the Kenyan government but also under the surveillance of British government departments, if information in the recently declassified files are anything to go by.

By then, he was living in London as a journalist after various stints at Kenya Broadcasting Corporation and Middle East newspapers in the late 1970s. He was on the BBC Staff until 1984, when he moved to the African Events, a London based publication on African Affairs as an Associate Editor. Even though Yusuf left the BBC staff, he continued to appear on the British broadcaster, to give expert opinions and analyses on political issues emerging in Africa.

In this role, he carved a niche as an independent journalist known for taking an independent line and expressing forthright views.

Government policies

But there was also no doubt that he was slowly becoming critical of the Kenyan government’s policies. By February 1987, he had become a fully blown political dissident, even launching an anti-Moi Movement called Ukenya. The movement which was launched February 18, 1987 in Friends House Euston Road, described itself as “an anti-imperialist organisation committed to struggle for democracy and the regaining of Kenya’s sovereignty”. While leading the movement, Yusuf continued to make regular appearances on BBC external Services programmes to offer expert political views, and also using the platform to mount his criticism against Moi’s government.

This triggered a protest from the Kenyan Ministry of Foreign Affairs which complained to the British High Commissioner in Nairobi. The High Commissioner would later report to the Foreign Office in a Telegram marked secret, “The Kenyan government have complained about programmes on the BBC External Services which contain criticism of the Kenyan government and in particular reference to or interviews with representatives of anti-Moi organisations like Mwakenya and Ukenya.

A particular irritation has been contributions to programmes by Yussuf Hassan.” He went on to inform the Foreign Office how Yusuf’s family in Kenya had disowned him because of his anti-Moi campaign in London.

The Foreign Office after receiving the complaint raised the matter with the BBC by forwarding the Telegram to Mark Dodd, the Controller of Overseas Services at the BBC, accompanying it with a note stating: “You may therefore be interested to see the enclosed telegram from Nairobi about Yussuf Hassan’s involvement in anti-government activities and clearly indicates that he can no longer be considered independent.” The Foreign Office was putting pressure on the BBC to rein in on Yusuf and prevent him from making antagonistic views on Moi’s government.

The BBC reacted by withdrawing Yusuf’s status as an expert and began referring to him as a politician. They also prevented him from commenting on key programmes such as Focus on Africa. Satisfied with this decision the Foreign Office telegrammed Nairobi, “External Services have decided to treat him as a politician rather than a journalist. And he will appear less frequently as an outside contributor.”

Ukenya was seen as a front organisation of the Muungano wa Wazalendo wa Kukomboa Kenya (Mwakenya), a revolutionary socialist organisation which had largely risen out of dissident intellectuals at the University of Nairobi in the late 1970s. Although Mwakenya had no identified leaders, Ngugi wa Thiong’o was a major ideological motive force behind it. It was organised along a cell system with Yusuf’s Ukenya being mentioned as its London cell. Yusuf was also described as a close associate of Ngugi.

“Mwakenya has sought to establish a number of front organisations in the UK. These include Ukenya and Umoja. The principal activist in London behind these organisations is Yussuf Hassan, an ethnic Somali and former broadcaster for the Voice of Kenya and the BBC,” read a document marked confidential prepared for the East African Department in the Foreign Office. Fearing that such activities could spoil the relations between Britain and its strategic partners such as Kenya, the Foreign Office decided to take a step.

There were already growing concerns about London becoming a centre for political agitation in view of the political happenings in Nigeria and Libya.

Confidential

In this regard, a memo marked “confidential” was circulated to all heads of department stating, “The Secretary of State feels strongly that the government should be able to take political action to ban trouble-makers from Britain if their presence is not conducive to the public good. Interpreted widely he does not see the reason why Britain should be used as a base for political activities against governments with whom we have good relations.”

The Home Office, which is the ultimate authority in relation to immigration matters or residence in Britain, began to take a keen interest in the movements and the stay of the dissidents in Britain. At a meeting between the Permanent Under Secretary Foreign Office and Permanent Under Secretary Home Office it was decided that policy towards foreign dissidents in the UK who plan political action or violence against foreign states was of interest to both departments. Deportation was considered as an option to get rid of such elements.

In 1988, The Foreign and Commonwealth Office wrote to the Home Office requesting details about Ngugi Wa Thiong’o and Yusuf Hassan and their immigration status, and if there was a possibility that they could be deported.

In a reply dated April 6, 1989, the Home Office stated that Yusuf Hassan was granted leave to remain in the United Kingdom in January 1984 by virtue of his employment with the BBC. The Home Office further informed the Foreign Office that “Whilst he (Yusuf) is not exempt from deportation, such actions could only be taken under Section 3(5)(b) of the Immigration Act 1971, on the grounds that the deportation is conducive to the public good.”

The Home Office’s view was that it would be difficult to justify the deportation of people like Yusuf Hassan whose nonviolent political activities were damaging to the UK’s relation with another country. “Yussuf Hassan is resident in the UK quite legitimately under the Immigration Act 1971 and there’s no evidence of him having been involved in any unlawful activity in this country.

In our view, there are no grounds for taking deportation action against Hassan.

If we were to seek to deport him the probability is that such action would provoke an asylum application which could ultimately leave us in a far more embarrassing position with the Kenyans,” the Home Office informed the Foreign Office. With their demands for drastic actions against dissidents having hit a snag after the Home Office became hesitant to play along, the Foreign Office settled on warnings and surveillance to keep the dissidents in check.

A document prepared the East African Department in the Foreign Office stated. “I conclude that we should go no further than having known members /sympathisers and its satellite originations, Ukenya and Umoja, watched and possibly warned by the Home Office in connection with applications and renewals to stay in the UK. If they wish to remain in the UK they must obey the laws, and in particular that they must not plot or advocate the violent overthrow of other governments.” Yusuf later worked for Voice of America, the UN before venturing into politics in 2007, becoming elected as the member of parliament for Kamukunji in 2011.

He serves as a member of the Committee on defence, Intelligence and Foreign Relations.

State spies

Commenting about the declassified documents this week, Yusuf told The Weekly Review that his home in London was once broken into by State agents. “The first time I attracted the attention of State spies was in June 1982, when we launched the Committee for the Release of Political Prisoners in Kenya. The committee came about as a result of a major security crackdown on Kenya opposition activists and the arbitrary detentions of hundreds of Kenyans by the repressive Moi-Kanu regime. We campaigned for the release of political prisoners Raila Odinga, Geroge Anyona, Mukaru Ng’ang’a, Edwin Oyugi, Ngotho Kariuki, and many others. By then, I was working for the BBC African Service.

“But most certainly in February 1988, when we launched a new political movement known as Ukenya in London with Ngugi Wa Thiong’o, Abdilatif Abdalla, the late Wanjiru Kihoro, Shiraz Durrani, and Wangui wa Goro, and I was named its inaugural chairman. At the time, Daniel arap Moi had a special relationship with Margaret Thatcher, and he wanted the UK government to rein in the growing exiled Kenyan opposition in London. Moi had attacked the BBC at a public rally and named me as the leader of the dissidents in London, using the broadcasting organisation as a political platform. He also ordered the detention of my father,” he said.

“I left the BBC and founded a new magazine on African affairs — Africa Events. Once again, their focus shifted to the staff and context of the new publication, which was independent and outspoken on developments in Africa. Twice, my house in Battersea in South London was broken into, and my belongings turned upside down, but surprisingly nothing was taken. They were presumably looking for documents or incriminating information that could have been used against me,” he added.