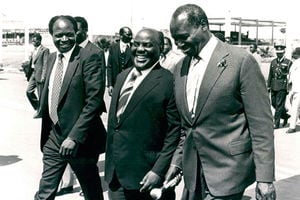

Jaramogi Oginga Odinga.

Just after Kenya gained internal self-government in 1963, the newly appointed Minister for Home Affairs, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga, went on a deportation spree targeting white setters, much to the chagrin of the British Prime Minister, Sir Alec Douglas-Home, who sent a strongly worded letter to Prime Minister Jomo Kenyatta.

According to recently declassified documents, when the then British High Commissioner to Kenya, Sir Geoffrey de Freitas, visited Kenyatta at Public Works Building, now Harambee House, to deliver the protest letter, Kenyatta was quick to throw Jaramogi under the bus, claiming that he had done so behind his back. This was despite the fact that he had personally instructed Jaramogi to carry out some of the expulsions.

“On the face of it, Kenyatta was saying that he had been bounced by Odinga, but this is hardly credible,” de Freitas wrote in a telegram marked “Confidential No. 1539”. The colonial government, well aware of Jaramogi’s progressive economic and social populism, which they felt posed a threat to British interests and white settlers in Kenya, had sought to curtail his influence in any future African government that was to be formed in Kenya. For instance, realising that Kenyatta was about to appoint him as Minister for Home Affairs on June 1, 1963, the Governor-General, Sir Malcom MacDonald, removed the police and internal security matters from the Home Affairs docket and transferred them to the Office of the Prime Minister.

The department of immigration, which fell under Jaramogi’s docket, was, however, considered inconsequential compared to the police and was, therefore, left intact in the Ministry of Home Affairs. Jaramogi, on the other hand, saw a loophole which he exploited to get rid of “hardline white settlers”. He had already marked a number of them, who he believed had undermined the fight for freedom, and were now out to sabotage the new African government and influence its policies. As he later stated, “The colonialists and their settler friends still pulled the strings”. He called them an “invisible government”.

The first British expatriate he expelled was Nyeri Police Chief Senior Assistant Commissioner of Police Leslie Pridgeon who, alongside Special Branch boss Ian Henderson, were behind some of the brutalities meted out on the locals by the police during the crackdown on Mau Mau between 1952 and 1960. Being a social populist, he convened a press conference during which he warned: “This is the beginning of the process of cleaning Kenya of all remnants of ill-intentioned imperialists forces. I wish to make it clear that the government will not hesitate to deal with any person whose presence in Kenya is contrary to national security.”

At a subsequent rally in Kangundo, he remarked: “The newspapers have asked me where I get information, I get it from the people. I ask all of you here to keep your eyes and ears open and report any colonialists to me. Even if it is your own father, you should report him.” He revealed that more expulsions would follow if colonialists or imperialists were to be uncovered.

True to his words, on July 1, 1964, just two days after deporting Pridgeon, Jaramogi declared Henderson persona non grata and ordered him to leave Kenya within 24 hours for his use of torture to put down the Mau Mau uprising. He also deported two Europeans for talking negatively about Africans in hotels. Attempts by the British High Commissioner to have the deportation delayed to allow the four to wind up their affairs were futile.

Even though Kenyatta had directly instructed Jaramogi to deport Pridgeon, he became exceptionally evasive when Jaramogi raised with him the question of deporting Henderson, the Scottish-born sleuth who had led the operation to capture Dedan Kimathi, the Mau Mau leader.

Ironically, Just the previous year after taking over as prime minister, Kenyatta had attempted to convince Henderson to extend his contract in the Kenya Police despite all the atrocities attributed to him. But according to one declassified document, “Henderson rebuffed Kenyatta’s magnanimous offer to retain him in police and was planning to leave at the end of his contract when Jaramogi caught up with him”.

Meanwhile, the Commissioner of Police, Sir Richard Catlin, having caught wind of Jaramogi’s plan, had visited Kenyatta and vowed to resign if Henderson was to be deported. Consequently, in order not to appear antagonistic towards the British and the white settlers in Kenya, Kenyatta gave Jaramogi a freehand with Henderson and told him to do as he wished with him. Surprisingly, when Jaramogi capitalised on this resolution and expelled Henderson, Kenyatta got annoyed and demanded an explanation on why he had done so without his approval. “When Mzee Kenyatta asked me why I had done so, I replied: ‘Mzee, you gave me full powers. I would have failed in my duty if I did not get rid of Henderson. He delayed our Uhuru,” Jaramogi would later recall during an interview with the Drum magazine in 1980.

On August 7, 1964, Sir Alec, seemingly angered with the expulsions of these British expatriates, wrote to Kenyatta expressing his resentment, arguing that such actions could affect the morale of British expatriates in Kenya, and put a strain on the diplomatic relations.

“I am greatly concerned at the reports I have received of the expulsion from Kenya of four more British citizens. Whilst I fully accept your government’s legal right to take this action, the abrupt and apparently arbitrary manner of these deportations, and in particular the use of this procedure to get rid of British officers who have given long service to the Kenya government, inevitably creates a bad impression,” the British PM informed Kenyatta in a telegram marked secret and stamped ‘Prime Minister’s personal telegram’.

This message was delivered to Kenyatta at his office at Public Works Building by Sir Geoffrey, who reported to London after the meeting, “Kenyatta greeted me most warmly and listened attentively as I explained to him the British prime minister’s concerns over the expulsion. After a while, he stopped and said ‘I know that I am very sorry. You can assure Sir Alec that this will not happen again except in real cases of emergency.” According to Sir Geoffrey, Kenyatta told him that Jaramogi had bypassed him in all the deportation cases.

However, the British diplomat found Kenyatta’s defence unconvincing, and wrote to London describing him as an insincere person. “Kenyatta is a devious Kikuyu,” his telegram read in part. He argued that there was no way Jaramogi could issue deportation orders without Kenyatta’s knowledge. In his conclusion, Kenyatta was a turncoat who was inciting Jaramogi to carry out the deportations while he himself stayed behind the scene pretending to be nice to the British.

“Political facts oblige Kenyatta to placate Odinga to a significant degree. He realises that by doing so, he is unable to upset us and Kenya’s immigrant communities and he does not want to do either of these things. Therefore, characteristically, he seeks to hold balance by gestures to both parties. In this case, he has sought to do so by giving Odinga the deportations and me a warm message for prime minister,” he stated. What he didn’t know was that just like them, Jaramogi was also being double-crossed on the matter by Kenyatta. By 1965, the responsibility for immigration had been transferred to the Office of Minister of State for Foreign Affairs, Joseph Murumbi.

As Jaramogi would later admit: “The Henderson deportation brought the wrath of British expatriate circles on my head as though I had acted independently of the PM and the Cabinet.” Henderson later moved to Bahrain, where as the head of Bahraini secret police, he oversaw the brutal crackdown on dissidents earning him the sobriquet, “Butcher of Bahrain”.

Mr Opiyo is a London-based Kenyan journalist and researcher