Kinyanjui Kombani.

I have met literati who heard of Kinyanjui Kombani’s first novel 20 years ago when it was released, but have never bothered to read it. I have met others who read a few pages and stopped, never to return.

One told me that he had read enough newspaper reports in 1991/1992 to know the story of election-related violence in Molo, Miteitei and Songhor so well that the last thing he needed was for someone to fictionalise that painful period.

Another said the word Molo is a trigger for horrifying personal memories so “I have never been able to read that book”.

Someone else asked me why a novel on that subject would be more important than the 1999 Akilano Molade Akiwumi Report, which had the findings of the Commission of Inquiry into Tribal Clashes related to the 1992 and 1997 General Elections.

Finally, two chronic book-buyers said that novel still sits on their shelves. They “just haven’t got round to it”.

I couldn’t afford to ignore new releases since I had been teaching literature at a public university from the late 1980s.

That era was marked by a sharp decline in fiction – perhaps not the writing of it, but certainly the publishing and public celebration of it. Transition, Busara and Ghala literary journals that started in the 1950s and 1960s, where many writers cut their teeth, were long dead.

The old(er) guard seemed to be in retreat for several reasons. Ngugi wa Thiong’o was in exile writing in Gikuyu for a select few while Grace Ogot was busy serving as a lawmaker and assistant minister in Daniel arap Moi’s government.

Sam Kahiga was battling publishers whose energy was now consumed producing textbooks for the 8-4-4 syllabus launched in 1985.

Every so often in this relatively quiet literary pool, a pebble dropped to stir the waters of the precarious politics and the perilous pandemic our country was grappling with.

Secret police

In Three Days on the Cross (1991), Wahome Mutahi defamiliarised fiction to narrate his torture in the dark dungeons where he had been detained without trial by secret police serving “the Illustrious One – a paranoiac despot”.

Meanwhile, David Maillu published a 1,121-page tome titled Broken Drum, a reckoning with the cultural politics of alienation that colonialism inflicted on us.

But our alienation had since acquired new dimensions. Carolyne Adala demonstrated this in one of the first novels about HIV, Confessions of an Aids Victim (1993). Many read it as biography not fiction, so scandalous gossip grew.

Soon, Margaret Ogola – a medical doctor – lent her voice to the battle to overcome stigma.

The River and the Source (1995) was quickly adopted as a high school textbook. Its 2002 sequel I Swear by Apollo met a quieter reception.

As stigma reigned and misinformation tormented us, Meja Mwangi joined the pandemic debate with The Last Plague (2000).

Author Kinyanjui Kombani.

This literary pool of occasional releases is the tepid pond into which The Last Villains of Molo appeared in 2005, under the Whistling Thorn series of Jimmy Makotsi’s Acacia Publishers.

Makotsi had kicked off the series in 2003 by taking a bold chance on a diligent Nairobi gardener Stanley Gazemba and his gripping tale of village life, The Stone Hills of Maragoli.

That was the year Binyavanga Wainaina used his Caine Prize money for his creative non-fiction story, Discovering Home, to start a literary journal, Kwani?. He seeded a movement.

However, it was Gazemba, Kombani, and Tobias Otieno, with his The Missing Links (2001), who marked the starting point in the third generation of Kenyan fiction.

They walked in the steps of Gatheru, Ngugi, Ogot, Ole Kulet(60s, 70s); Ogola, Mutahi, Marjorie Oludhe Macgoye, (80s and 90s) and approached old themes with new methods.

Gazemba’s novel won the 2003 Jomo Kenyatta Prize for Literature while Otieno’s was runner-up.

Kombani’s went largely unnoticed. It was not until 2013 that it made it to the annual bibliography of new writing from East and Central published in the Journal of Commonwealth Literature.

So does The Last Villains of Molo, matter? Definitely. Kombani provides a vivid cultural history of the 1990s and 2000s when the pool table was the prime public sphere for youth; when Kalenjin Sisters were chart-stoppers; when K-South, Kalamashaka, Mashifta and Ndarlin’ P redefined popular music; when matatus in all their volume and visibility proclaimed the validity of urban belonging, and when “mchogoano” morphed from a children’s pastime to anchor Hip Hop performances at Florida 2000.

Kombani matters because he documents our embedded practice of political violence, which historians have dubbed “killing the vote”.

This state-sponsored violence has shaped narratives of identity, belonging, entitlement and political power since colonial times.

Kombani is sympathetic to bewildered villagers thrown together by political settlements made elsewhere; settlements where tensions between the logic of pastoralism and the moral economy of tillers of land are inevitable.

“You can’t escape the long arm of the tribe,” says Angelina Chebet, a character driven by a thirst for revenge.

Hers is the kind of retaliatory violence that led to the killing of Captain Edward Belsoi, an incident that Kombani paints with admirable scrutiny.

As he unpacks the psychological impact of childhoods of bigoted tales, watching cold betrayals between neighbours and being oathed into tribal armies of murderers, Kombani shows us new ways to conceive of the self; to forge community; to rebuild a nation in which revenge is shunned even when justice is unavailable.

Kombani does not always trust his readers to join the dots or to bear with suspense.

Sometimes he misses the balance between showing and telling and leads his reader by the nose. For instance, the question at the end of Chapter Two is unnecessary. Likewise, the literal translation of every non-English word bogs down the reader.

Nonetheless, as he moves from the drama in Nairobi’s clubs, slums, streets and cemeteries to the battlefields of Olenguruone, Ndoinet, Kamwaura and Molo, Kombani directs the reader with a precision that beats Google Maps and a fine mastery of imagery – every forest, every stream, every street crossed, every tombstone, details a war, including the terror of HIV/Aids. In all these wars, the poor are the real victims.

PHOTO | FILE Author Kinyanjui Kombani.

The central characters – Bomu, Bafu, Rock, Bone and Ngeta, the polyglot born in Mumias – reveal a new identity devoid of tribe.

Hard names for the hardened illustrate the violence of the places they hail from, including “The Slaughterhouse”, that nine-by-nine room they inhabit in Ngando, Nairobi. Their experiment with post-tribalism is thrown into precarity by the arrival of Nancy, a typical babi whose real danger remains unknown to them. The fact that Bone and Rock eventually turn Nancy into their way of thinking is a victory.

They return to Molo 10 years after they left. Bone is full of nostalgia for this lush place; an area whose fertility is fed by cycles of bloodshed and tears of the fleeing, the (dis)placed.

Kombani does not address the question of how another season of blood-letting for elections, in 1997, might have changed the place or his characters.

As graphic as Kombani’s historical novel is in capturing place and time, the hope that underpins his prophesying title forces him to side-step some of Molo’s tortured (hi)stories. For this is the same place of contentions that Ngugi alludes to in A Grain of Wheat (1964) where squatters lost their land in the 1940s and were ferried to Gikuyu reserves.

Kombani’s hope in a new generation defies histories that fester and wallow in victimhood, unaired by scrutiny, untreated to healing. And justice? Fiction such as Kombani’s augments judicial reports. It interrogates character to reveal the layers of motivation. It ventilates grief. It elicits empathy rather than outrage. To that extent, it shapes perspective and promotes understanding.

With this novel, Kombani stormed the cemetery where we buried Moi-era memories. And he did so with depth, compassion and hope. If our publishers had budgets for book tours, this novel might have achieved the same outcome of a national conversation as Nyamisa Chelagat’s #FufuaICC did on X in December 2024.

Still, even without a book tour, university courses, bloggers’ reviews and one academic study to date by Julius Chepkwony, see value in Kombani’s novel.

It builds on the Ngugi-Mutahi-Macgoye practice of (re)writing history as fiction. Discussions are underway between Kombani and cinematography Martin Munyua on how to amplify The Last Villains of Molo as film.

When our politicians, once again, ignited tribal suspicions into viral infernos, we got Healing the Wounds (2009), a collection of non-fiction narratives of the 2007/2008 post-election violence (PEV). Ngugi revisited his childhood memories, Dreams in a Time of War, in 2011. The memory of singing “convoys of the caged” on the Nakuru-Nairobi road is about squatters who were ferried in lorries from “Ole Ngurueni” to Limuru and Yatta.

In 2014, Yvonne Owuor’s novel Dust unearthed our ledger of assassinations while Wanjiru Koinange’s The Havoc of Choice focused on PEV in Nairobi.

Early last year, Scholar V. Akinyi released Hop, Skip and Jump, a children’s story of the violence that tore Naivasha in January 2008.

Akinyi’s fiction found resonance in the recollections of social media users who responded to Chelagat’s hashtag with posts about childhoods destroyed by divisive politics they neither understood nor subscribed to. No one has ever been held accountable for the killings, violence and destruction.

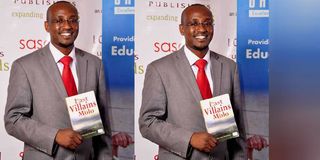

From his early dive into fiction, Kinyanjui Kombani – now a banker based in Singapore – has grown into an award-winning writer of children’s and YA fiction. His place in the pantheon of Kenyan literature may not be the stratosphere, but it is secure.

Dr Nyairo is a Cultural Analyst – [email protected]