Various American interests have converged in favour of President Ruto, widely viewed as the West’s favourtite African leader.

| FileWeekly Review

Premium

Why President Ruto is America’s new ‘Mr nice’ in Africa

It was President William Ruto’s week to shine. The spotlight was on him as the international media sought his sound bites and the galaxy of continental and global figures assembled in Nairobi for the three-day African summit on climate change.

Besides driving himself from State House to the venue in an electric car, the President stole the show in the streets and at the podium. But more than that, the accolades he got from the US delegates indicated that Dr Ruto is the new Mr Nice in Africa.

President Ruto, who marks his first year in office on Wednesday, has catapulted himself to the center of African politics and captured leaders’ attention with his pan-African approach to international matters. As chairman of the Africa Committee of Heads of State and Government on Climate Change (CAHOSCC), President Ruto is at the heart of a global discourse that allows him to be the African spokesman on climate change as the UN prepares for COP28 UN Summit from November 30 to December 12 in Dubai.

That Dr Ruto is receiving attention from the right corners of Washington DC was not in doubt. Of late, the flow of accolades and US delegates to State House, Nairobi, confirms that he is the new kid on the block.

US President Joe Biden and First Lady Jill Biden pose for a photo with President William Ruto and his wife Rachel during the US-Africa Leaders Summit at the White House, USA, on December 14, 2022.

Former US Secretary of State John Kerry had all the good words for President Ruto: “Mr President,” he said, “I have a feeling that after that extraordinarily powerful presentation, nobody should say anything; we should just act. President Ruto is showing the path for everyone to follow. Your leadership is palpable. You have set a clear path for us. Africa is meeting. Africa is talking. Africa is deciding.”

Last July, US President Joe Biden sent two senior members of his administration to Nairobi led by Katherine Tai, the Principal Trade Advisor and Spokesperson on US trade policy. President Ruto also later held talks with Brian Nelson, the US Department of Treasury’s Undersecretary for Counterterrorism and Financial Intelligence.

The arrival this week of Kerry, the US Special Presidential Envoy for Climate Change, was an indicator that President Ruto is now the man to watch for he has the right contacts in Washington. By praising Dr Ruto, Kerry echoed the words of US Ambassador Meg Whitman, who, in mid-August, praised Kenya as the most stable democracy in Africa.

“Kenya held what many analysts said was the freest, fairest and most credible in Kenyan history,” Whitman had said. While Whitman’s comments had led to uproar from opposition leader Raila Odinga – who dismissed her as ‘a rogue ambassador’ – the Cabinet Secretary for Foreign and Diaspora Affairs, Dr Alfred Mutua, said she was “forthright and honest” and that “she stated facts and paid tribute to the democratic way our constitutional institutions oversaw a credible electoral process that has set Kenya on a transformative path”.

US Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry with President William Ruto on the sidelines of Africa Climate Change. Inset: US President Joe Biden.

The US views Kenya’s democracy as growing – having gone through the test of nationhood during the 2007/8 post-election violence. As the most developed country in the region, Kenya’s stability is also vital for US strategic interests. As part of its foreign policy, the US treats the eastern and Horn of Africa as strategic, with Kenya sitting as the most stable among the nations, and Ruto finds himself in the right place. “Kenya is Washington’s most capable and trusted security partner in East Africa and enhanced trade with and investment in democratic and modernising partners like Kenya is a strategic win for the United States,” former US Ambassador, William Bellamy, said last year.

If Dr Ruto plays his cards right, he will be an influential figure within Africa as long as he has the confidence of the Biden administration. Again, he has to stabilise local politics, too. Because of that, the US has been leading efforts to stabilise the post-election uncertainty in the country and had sent Sen Chris Coons, a close ally of President Biden, to meet with President Ruto and Odinga.

It is believed that these efforts led to the ongoing 10-member bipartisan talks between Azimio la Umoja and Kenya Kwanza to address some of the nagging administrative issues – including electoral injustice. President Ruto is also keen on the bipartisan talks. After all, he would be of no continental use brokering peace from an unstable nation. Again, the US – which has a military base in Kenya – relies on the nation’s stability to overlook the eastern ream of the Indian Ocean.

President William Ruto with US Senator Chris Coons and Ambassador Meg Whitman at State House, Nairobi.

Africa is strategic for the US because it will account for 15 per cent of the world’s population by 2050. Again, it holds 30 per cent of the world’s reserves of critical minerals and 28 per cent of the United Nations voting groups. It also has to seek allies against China and Russia, and courting strongmen in Africa is one of such strategies – an age-old US practice.

In the region, President Ruto is playing a role in stabilising the Democratic Republic of Congo, where he has appointed former President Uhuru Kenyatta as his peace envoy. The DRC is a new playground of various commercial interests. The US Africom has been engaged for over a decade in training the Congolese army and it regards the DRC as a strategic reservoir of wealth in Africa for it is home to 30 per cent of the world’s critical mineral reserves, many of which – cobalt, lithium, manganese, graphite, and nickel – are essential to renewable and low-carbon technologies. DRC accounts for nearly 70 per cent of the world’s cobalt supply and is thus of strategic value.

Kenya’s involvement in the DRC feeds into the narrative of US strategies in Africa. Interestingly, DRC caused the fallout between the US and President Paul Kagame of Rwanda, who previously used to be in Washington’s good books. Last month, he said that the US love for DRC is to scramble its minerals and, thus, treats Rwanda as “an afterthought”.

In November last year, President Ruto sent 1000 troops to the DRC to fend off the M23 rebels allegedly backed by Rwanda. While M23 are mainly Tutsis, Kagame has always denied that accusation and argues that the rebels are products of mismanagement. It is such a crisis and Kenya’s stability that naturally brings President Ruto into the picture and allows him to extend his influence beyond the borders with the backing of the US. This week, President Ruto lifted visa requirements for Congolese seeking to enter Kenya, and a week later, DRC announced similar measures. Those are more than bilateral interests.

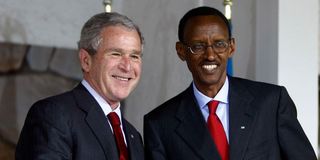

US President George W. Bush (left) shakes hands with President Paul Kagame of Rwanda at a joint news conference in Kigali on February 19, 2008. Kagame used to be East Africa’s Mr Favourite.

By continuing to play a leading role in stabilising Somalia and the DRC, President Ruto has become the new regional poster kid – though he failed to penetrate the Sudan crisis after his mediation attempt was rejected by General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan who is at war with his rival, RSF leader Mohamed Hamdani Daglo.

Under the August 2022 US strategy on sub–Saharan Africa, President Biden said that the US “path towards progress rests on a commitment to working together and elevating African leadership to advance our shared agenda”. Part of that policy was to increase US investment and trade with Africa, and it appears that Kenya is a choice destination for that. By sending Whiteman, an entrepreneur-diplomat, to Kenya, Biden pointed to the role Kenya was to play in his agenda.

Kenya is also surrounded by the unstable Somalia and the volatile Ethiopia and Sudan. Dr Ruto is currently the most energetic of the regional leaders and has eclipsed Kagame, President Yoweri Museveni of Uganda and Tanzania’s Samia Suluhu Hassan. His rise could only be stopped by domestic troubles.

With a struggling economy and a myriad of promises, President Ruto knows that a political crisis would drive away investors – and, more than anything else, spoil his presidency. With one year already gone, he has to stabilise the country for investment at a time when the Kenyan shilling is under pressure from a strong dollar and the debt crisis is threatening social services. Dr Ruto has opted for commercial-diplomacy to attract investments into critical sectors such as agriculture and financial services – even as he tries to expand credit for small and medium-sized enterprises.

President William Ruto and First Lady Rachel Ruto at the reception hosted by US President Joe Biden on the occasion of the 77th United Nations General Assembly.

The climate change agenda has given Dr Ruto a chance to call for a debt payment moratorium in the hope that it could rescue him. Biden has also been pushing for an African agency. The Nairobi summit was one such opportunity where Africa took leadership of its agenda as part of the global community. It is this space that Dr Ruto has occupied as the new point man.

Kagame used to be East Africa’s Mr Favourite. And so was Museveni. In Washington, they previously won accolades and best political adjectives. For instance, in 2020, The New York Times described Museveni as “the Pentagon’s closest military ally in Africa” and as a “brilliant” personality. That was until he signed the anti-gay laws. Kagame was – as The New York Times called him – “Global elite’s favorite strongman”. But after the Clinton-Bush-Obama honeymoon was over, both were portrayed by Western media as “brutal dictators”.

Kagame is unmoved: “We’ve made it clear there isn’t anyone going to come from anywhere to bully us…,” he told The New York Times last year. He called the US policy towards the region as enigmatic and hypocritical – according to the intelligence newsletter Semafor.

As Dr Ruto enjoys global attention, he has to fight the battles at home by stabilising politics and the economy. Kenya, a fast-growing economy in the last decade, has been advocating for debt relief in the hope that it could navigate the US$2 billion Eurobond, which is maturing in June 2024 and which saw the country’s debts classified at high risk of distress – despite the previous record that judged the obligations as sustainable. Kenyatta’s borrowing spree for infrastructure projects left the country with a heavy burden and fears that Kenya could default on payments. At the end of 2022, the external and domestic debt components accounted for about 67 per cent of GDP.

Besides those economic troubles, Kenya is seen as a democratic stronghold compared to Uganda and Rwanda, which were previously highly regarded by the US. Whatever happens, President Ruto is now Mr Nice.

[email protected] @johnkamau1