Breaking News: Former Lugari MP Cyrus Jirongo dies in a road crash

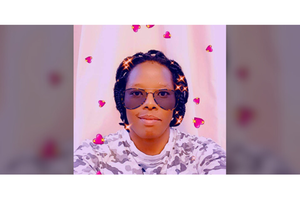

Ms Penina Wanjiru, 31, a resident of Bahati in Nakuru County, whose three-year-old daughter has been trapped in Saudi Arabia for more than five months. Ms Wanjiru travelled to Saudi Arabia in 2019 and was deported back to the country in March 2025, leaving her daughter behind.

When Penina Wanjiru boarded a flight to Saudi Arabia in 2019, she carried with her the hope of a better future—both for herself and for the family she left behind in Bahati, Nakuru County.

Like thousands of Kenyan women who seek employment in Gulf countries each year, Wanjiru believed that working abroad would offer a chance to lift her family out of poverty and support her three children.

She had secured a job through an agency that promised a stable salary, a caring employer and good working conditions.

For a while, things went according to her plans.

Read: Dead in Oman, held hostage in Kenya: Man denied right to bury wife over unpaid Sh146,000 dowry

Ms Penina Wanjiru, 31, a resident of Bahati in Nakuru County, whose three-year-old daughter has been trapped in Saudi Arabia for more than five months. Ms Wanjiru travelled to Saudi Arabia in 2019 and was deported back to the country in March 2025, leaving her daughter behind.

For nine months, she worked diligently as a domestic worker, enduring long hours, homesickness and cultural barriers. Her dream was simple: send money home, educate her siblings and eventually start a small business after completing her contract.

However, life took a painful turn. Her employer began mistreating her, forcing Wanjiru to report to the recruitment agency that had facilitated her travel. She hoped they would help her secure a different household to complete her contract.

“After some weeks they finally let me go. They helped me with the process. I was so happy. I didn’t know it was a trap. At the airport I was told my ticket was fake, and I was left stranded. When I called my boss, they told me they were done with me and I should find my own way home,” recalled Wanjiru.

“I had no money. I had used everything I had to purchase the air ticket. So, I got in touch with other Kenyans in Saudi Arabia who agreed to host me and help me secure employment. That is how I ended up remaining in Saudi Arabia,” she explained.

A secret pregnancy

According to Ms Wanjiru, she was fortunate to get another job, but life again took an unexpected turn in 2021 when she became pregnant, news that brought both joy and fear.

“Pregnancy in Saudi Arabia for a domestic worker is complicated, as many women lose their jobs or face punishment when they become expectant,” she said.

Fearing deportation, she did not inform her employer or the authorities about her pregnancy.

“In Saudi Arabia, the law prohibits pregnancy out of wedlock, so I chose to keep it a secret until I delivered a healthy baby girl, whom I named Precious. On the day I delivered, I called a doctor who helped me give birth at home. I cared for her and when she was seven months old, I started leaving her at a daycare as I went to work. I kept her hidden from authorities,” she recalled.

Ms Penina Wanjiru, 31, a resident of Bahati in Nakuru County, whose three-year-old daughter has been trapped in Saudi Arabia for more than five months. Ms Wanjiru travelled to Saudi Arabia in 2019 and was deported back to the country in March 2025, leaving her daughter behind.

But in February 2025, everything fell apart. One day, when she and her roommate had just returned from work, police officers stormed their house. Without allowing them to pick up their belongings, the officers forcefully escorted them to a police station, where they were detained for three days.

They were later transferred to another facility where they waited for more than two weeks as deportation procedures began.

“Luckily, the embassy was alerted and some officials visited us. I informed them about my baby, who was now three years old. The officials promised that my daughter Precious would be brought to me from the daycare, but that never happened. I was deported back home, leaving my daughter behind in the care of a woman at the daycare,” she told the Nation.

Upon her arrival in Kenya, she received a distressing message from the woman informing her that the child might be sent to an orphanage as the process of deporting her to Kenya was taking too long.

“Before I was deported, I told them I would not leave my daughter behind, but I was beaten and threatened by the police. I just had to come home without her. I pleaded with them to allow me to leave with my daughter, but they ignored me. I last spoke with her in April 2025,” Wanjiru said.

“I was told I have to do a DNA test, but I have been banned from going to Saudi Arabia for five years. The process is taking too long, and all I want is my baby,” she added.

Today, the 31-year-old mother’s voice trembles as she recalls the moment everything fell apart. Instead of enjoying motherhood, she was deported in March 2025 without her child.

Five months of torment

More than five months later, Wanjiru continues to live in torment—her days filled with fear, uncertainty and desperate hope that she will one day hold her daughter again.

She vividly remembers her last moments in Saudi Arabia—how she begged to hold her daughter, how she pleaded for just one last hug—but was forced to leave to avoid complicating the deportation process.

Wanjiru arrived back in Nairobi without luggage and, even worse, without documents proving her parental link to her child, making the process of reclaiming her daughter even more complicated.

Back home, she found herself in an emotional and financial crisis. With no savings and no job, she depended on relatives while dealing with the trauma of losing her child.

“It is the most painful thing a mother can go through. I came home with empty hands and an empty heart. My daughter remained behind, and I have no idea if she is safe or how she is doing. I last spoke with her in April through a video call. I just miss her,” she said.

Since her return, Wanjiru has made endless trips to government offices, agencies, and human rights organisations, hoping to begin the process of tracing and repatriating her daughter.

But every step has brought new obstacles.

The recruitment agency has been unresponsive, she says. Some officials have told her that her case is “too complicated,” while others have advised her to “be patient”—a luxury she says she no longer has.

“I don’t know where my baby is now or who is caring for her. My child is growing without me,” she said.

Part of her fear stems from the uncertainty surrounding her daughter’s citizenship status. Saudi laws, she explained, make documentation for children of migrant workers complicated—especially when the mother is deported before the process is completed.

She still hopes to meet her daughter again.

Asked how she copes with the emotional toll, Wanjiru pauses before replying, “I pray. That is all I have. Some days I feel like giving up. Other days, I wake up believing that something will change, that someone will help me.”

The Nation has learned that Wanjiru’s case is not isolated.

Dozens of other mothers who gave birth in Saudi Arabia are struggling to register their children as citizens.

On November 14, the Ministry of Foreign and Diaspora Affairs released a statement addressing concerns regarding Kenyan mothers and their undocumented children in Saudi Arabia, saying the government has implemented various measures to help in their repatriation.

According to PS Roseline Kathure Njogu, registration of the births of nationals occurring abroad is well regulated under the Kenya Citizenship and Immigration Act (Cap 170) and the Births and Deaths Registration Act (Cap 149), with the responsibility resting on the parents.

She noted that Kenya Missions Abroad are mandated to receive birth notifications in prescribed forms—with sufficient particulars—and facilitate registration.

PS Njogu said that under Kenyan law, there is no distinction in the treatment of births based on the mother’s marital status. The rights of Kenyan children do not derive from their parents’ marital status—unlike in Saudi Arabia.

According to Saudi law, pre- or extramarital sex is illegal and carries severe penalties, including arrest, imprisonment, and deportation. As a result, pregnancies and births resulting from such relationships are considered evidence of an offence.

Low turnout for DNA initiative

Fearing legal consequences, some women give birth at home with the help of unqualified midwives. A marriage certificate is required by Saudi authorities to issue a birth certificate. Therefore, single mothers delivering children out of wedlock are often unable or unwilling to register these births.

Ms Njogu noted that the government launched an inaugural DNA sampling initiative in 2023—under the transformative Mobile Consular Services dubbed “the Mwanamberi Project”—to help affected parents and children acquire birth certificates.

However, turnout was low. Fewer than 1,000 individuals came forward, yielding 707 DNA samples—388 from children. Only 113 people applied for birth certificates, of which 110 were successfully processed.

The Ministry contacted all 110 parents through messages, calls, and community notices to collect the certificates from the Kenyan Embassy in Riyadh. To date, only a third have done so.

The donors of other samples were also contacted and advised to complete their birth certificate applications, but responses remained low.

Beyond the Mwanamberi Project, the Kenya Embassy in Riyadh established a Joint Interdepartmental Working Group (JIWG) with Saudi authorities—including the Saudi Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the General Directorate of Passports (Jawazzat), the Ministry of Labour, and the Ministry of Interior.

The PS noted that this collaborative mechanism created a lawful pathway for repatriating Kenyans, resulting in the safe return of 59 mothers and 73 children.

The Kenyan government also negotiated an amnesty for undocumented individuals to regularise their status and return home without penalty—an amnesty granted by the Saudi government.

“We urge single mothers in Saudi Arabia with undocumented children to utilize the pathways created by the Kenyan government to regularize their status and secure documentation for their children,” the statement read.

“We further urge those whose birth certificates are lying at the Kenya Embassy in Riyadh to collect them immediately. We remind all diaspora parents blessed with children abroad of their responsibility to register those births to protect their children’s rights and interests.”

Follow our WhatsApp channel for breaking news updates and more stories like this.