Breaking: Autopsy reveals how Cyrus Jirongo died

Language preference in Kenya has tilted in favour of English, and to some extent Kiswahili, at the expense of mother tongue.

Achieng Odundo pronounces English words with the British accent. In fact, having a conversation with her might make an ordinary English speaker shy off for fear of not being as fluent as she is. This spoken fluency did not just come naturally; she worked hard to learn it.

“Speaking English was an achievement, especially because I grew up in the village where the language was only used in schools to teach and write exams. There was written English, which we knew to read and write, but spoken English was prestigious,” says the 36-year-old.

Ms Achieng Odundo and her 11 years old son who was taught mother tongue by her nanny.

During the interview at her house in Nairobi’s Greatwall Gardens, Ms Achieng takes us back to three decades ago when she was a young girl going to school on bare feet just like her fellow schoolmates. They all used to speak their mother tongue. Their teachers, she recalls, had no choice but to use their mother tongue to teach so that learners could understand them.

Just when she was to join the upper primary class, a tragedy struck her family. Ms Achieng’s mother died, leaving her under the care of a caregiver who then requested her transfer to Lwak Girls Primary Boarding School. This is where she started speaking Kiswahili and English, as it was a school rule.

“On certain days, we were required to speak English for half of the day and Kiswahili for the other half,” she recalls.

Read: How to raise Gen-Alpha

Being in a school that had the majority of children, some younger than her, speaking English and Kiswahili in their daily conversations, motivated her to learn the languages, even though it was difficult.

“It was hard to keep my tongue in English the whole day for three days a week, but it trained us, and by the time we finished primary school, our tongues got used to the language. I was fluent and confident, and it made my guardians very proud,” says Ms Achieng.

When she became a mother 11 years ago, she set a rule that her child must only be spoken to in English. Reason? She wanted to save him the trouble of learning the language the hard way.

Millennial parent

“In 2014, when I had my baby, I was an ambitious millennial parent who did not want her child to speak their mother tongue because it was fancy for your child to speak in English or Swahili,” she says.

Being a working mother, she hired a nanny to take care of her baby. She informed her nanny that she was to only speak English with the baby, and this worked well for nine years. Her son did not know how to say anything in his mother tongue (Luo).

“Everyone used to admire him and say, ‘Oh my! That child is small and speaks English very well. Even in the kindergarten that he attended, the teachers used to ask me, “how does your son speak English so well?” says the mother of one.

“During family gatherings, my relatives would ask me which school my son went to because everyone believed that fluency had a lot to do with the school. When they realised that I had home-trained him to speak English, they would be impressed.”

Later on, she got another nanny who defied the English-speaking rule.

“She speaks to my son in Luo and treats him like her son. I am okay with it now, after all, he does know how to speak the language.”

Fading mother tongue

Language preference in Kenya has tilted in favour of English, and to some extent Kiswahili, at the expense of mother tongue, especially in upper-market homes and those in inter-tribal marriages. To blame are parents who do not talk to their children in their mother tongue or intertribal marriages, where the parents wonder which language to pass on to their children.

Interestingly, however, some parents are depending on their nannies to pass down mother tongue to their children. One parent, a Kamba by tribe, who spoke to Lifestyle, says her nine-old son now speaks four languages; Luo, which he learnt from his nanny, Kamba and Swahili, which he learnt from her, and English which he learnt in school. She loves the fact that her son is multilingual even though she does not understand him when he switches to Luo language to speak with the nanny.

Sometimes, she is feels abit left out when her son and nanny switch to Luo and chat animatedly, leaving her in the dark.

Damaris Lubanga is an Advocate of the High Court. She was taught mother tongue by her nanny who raised her for over six years.

Elsewhere in Nairobi, we meet Damaris Lubanga, an advocate of the High Court and programmes officer of access to justice at Pendekezo Letu, an organisation that assists vulnerable children. She was born, raised and lives in Nairobi. Her parents went to work every morning and returned home in the evening, which limited her interaction with them to a few hours in the evening and on weekends.

“I would be at home with my nanny, and she talked to me a lot because she was the one who was with me. The stories I hear are that I was a very healthy child because of her. She took care of me like her own,” says Ms Lubanga.

Her parents come from different communities. The nanny who raised her in her formative years was Luo, just like her mother, and is the one who taught her how to speak Luo fluently.

“My nanny would sing a lullaby to me in my mother tongue. Sometimes, if I did something bad, she would correct me in Luo gently. She never used force on me. Through that, I got to learn that my mother tongue is a beautiful language of love,” she says.

She recalls that her parents were surprised to hear her speaking Luo fluently.

When this nanny left after Ms Lubanga turned three years, her parents employed a few more nannies who took care of her, and although they came from different communities, they did not teach her their mother tongues. They preferred speaking in Kiswahili.

“My first nanny was very instrumental because it is very difficult to learn a language as an adult. A child learns a language from experience, and when the mind is more active.”

Learning her mother tongue at a young age, she says, has been beneficial for her career.

“When I have clients who can only speak in Luo, I can connect with them, and this means that we are able to offer better services and give them the justice that they deserve.”

Although she is not yet a parent, she says that she would welcome her children to learn their mother tongue, since she has experienced the benefits.

Allure of foreign languages

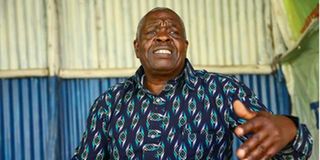

Today’s generation prefers to speak foreign languages rather than their mother tongue. This is according to the founder and CEO of Kenyan Aged People Require Information, Knowledge and Advancement (KARIKA), Mr Elijah Mwega.

Mr Elijah Mwega, founder and CEO of Kenyan Aged People Require Information, Knowledge and Advancement.

“They speak English without caring whether their grandparents understand what they are saying. You can imagine a family where parents, children and grandparents are all present, yet the grandparents, who carry rich stories and deep wisdom, cannot share them because of language barrier,” says Mr Mwega.

He recalls that during his childhood in Gatundu, Kiambu County, community gatherings were common, and people spoke their mother tongue everywhere they went. This, he says, made it easy for children in his generation to learn their mother tongue naturally. Living closely with older people also made it easy for every child to pick up the language.

However, things have changed due to increased urbanisation and Western cultural influence.

“Back then, speaking my mother tongue was normal. We should appreciate nature and understand that we are unique as a country with many tribes. All over the world, people know where they belong. A generation that does not speak its mother tongue not only excludes older people from daily conversations, but also forgets its roots,” he adds.

With Kenya having more than 40 ethnic communities, Mr Mwega notes that many elderly people can only speak their mother tongue, adding that it would be unfortunate if such people cannot communicate with their grandchildren simply because the younger generation does not speak the language.

He attributes the shift from speaking mother tongue at home to the growing preference for English, to changes in the academic syllabus and the desire for employment opportunities with foreign companies, locally and abroad.

“We are so focused on foreign countries that we forget our culture and where we belong. Even our schools no longer teach mother tongue, yet during my school days, it was one of the subjects taught.”

Despite parents wanting to position their children competitively for education and job opportunities, Mr Mwega says they should still normalise speaking their mother tongue at home.

“If you want to succeed in life, you must own your origin. Charity begins at home. Our young generation no longer starts at home; they start with English and work backwards,” argues Mr Mwega.

Follow our WhatsApp channel for breaking news updates and more stories like this.