Turkish national Necdet Seyitoglu was among the seven people abducted in Kileleshwa, Nairobi on October 18, 2024.

It was at the Hotel Intercontinental in Nairobi, some six years ago, that I found myself seated across from Mustafa Genç – one of the Turkish exiles kidnapped from Nairobi this week.

The air was thick with unease as Genç, now thrust into international limelight, sat beside a fellow countryman. Both were glancing anxiously over their shoulders.

The lunch before us was a mere formality – since the two men were already consumed by anxiety and seemed lost in a labyrinth of uncertainty. They feared that President Yecep Erdogan had sent kidnappers to abduct them.

They were right.

“Do you want me to tell your story?” I asked voice lowered, sensing the gravity of his silence.

“Not yet,” he replied, almost in a whisper. At the time, Genç was not just any expatriate; he was the principal of Light Schools Academy and the head of the Harmony Institute, a beacon for interfaith dialogue in Nairobi.

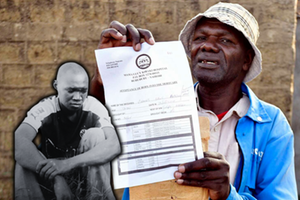

Mustafa Genç, former principal of Light Academy.

But headlines were the last thing he desired. What he wanted was for me to grasp the plight of the Turkish exiles scattered across Kenya — their anxiety, their uncertainty, the slow-burning dread that gnawed at them day after day, as they waited for a shadow that would inevitably fall. We met several other times.

This week, that long-feared shadow came to life, sweeping Genc and seven other Turkish nationals off the streets of Nairobi. The same nightmare that had lurked in the corners of his mind had finally ensnared him.

According to reports from the Stockholm Center for Freedom, Genc, along with Huseyin Yesilsu, Ozturk Uzun, and Alpaslan Tasci, was seized in what many believe to be an operation orchestrated by Türkiye’s National Intelligence Organization (MIT). Their crime? Their connection to the Gülen movement, a movement of educators, thinkers, and advocates of peace, now hunted across the world like criminals.

Others, including Mustafa’s son, Abdullah Genc, British citizen Necdet Seyitoglu, and Saadet Tascı, were briefly swept up in the operation but later released.

Seyitoglu recounted to the media the terror of being intercepted by armed men, blindfolded, handcuffed, and driven into the unknown, only to escape captivity by the merit of his British passport. His phone and laptop, though, vanished with the abductors.

Battleground for geopolitical drama

Kenya, long perceived as a distant refuge, has unwittingly become a battleground in a far-reaching geopolitical drama, a stage upon which the bitter feud between Turkish President Erdogan and the exiled cleric Fethullah Gulen, who died on Saturday.

What had once been a harmonious partnership between the two — Gulen’s movement, Hizmet, focusing on education and dialogue, and Erdogan’s government — has devolved into a deadly vendetta.

Exiled in the US, Gulen was cast as the villain in Erdogan’s narrative of power, accused of infiltrating the Turkish state. The crackdown that followed within Türkiye has reached far beyond the country’s borders, ensnaring even those who sought sanctuary in foreign lands.

And so, Nairobi finds itself drawn into this dark theatre, where two Turkish forces are at loggerheads.

Genc, who had devoted seven years to nurturing young minds as principal of Light Schools Academy, is nowhere to be seen, taken near Nairobi Arboretum as he drove. His role at the Harmony Institute, a symbol of interfaith solidarity in Nairobi has been eclipsed by the cold, harsh reality of international power struggles between Erdogan and Gullet.

Amnesty International has already voiced concern over the abductions and said they feared that the seven are at “grave risk of refoulement.”

“This incident constitutes a breach of both Kenyan and international refugee law. These individuals are refugees who have sought the protection of the Kenyan government. Their abductions underscore the growing concern about the safety of all refugees and asylum seekers in Kenya,” said Irungu Houghton, Amnesty International Kenya director.

This is not the first time that Erdogan’s regime has reached across borders to snatch its perceived enemies. In June 2021, Orhan Inandi, a Turkish-Kyrgyz national, vanished from the streets of Bishkek, the capital of Kyrgyzstan. His car was found abandoned in the quiet of the early morning.

Days later, a haunting image emerged—a photograph of Inandi, handcuffed, in Türkiye. The founder of a network of schools in Kyrgyzstan tied to the Gulen movement, Inandi had become yet another casualty of a global game of shadows.

Turkey’s history of abductions stretches much deeper than recent headlines suggest. Between 1990 and 1999, as the conflict with the Kurdish insurgency raged, the Turkish state embarked on a grim campaign of kidnappings, targeting anyone—real or imagined—who aligned with the Kurdish cause.

And it was in Kenya, a land once believed to be far beyond Türkiye’s reach, that they captured the notorious Kurdish leader Abdullah Ocalan, demonstrating that no corner of the world was safe from their grasp.

Media outlets are now awash with reports of Turkish citizens abducted from exile, vanishing into the murky depths of international intrigue. Many of these extraterritorial kidnappings have ended in torture—or worse.

Zabit Kişi, for instance, was spirited away from Kazakhstan in 2017. Once back in Turkey, he disappeared, held in a secret prison for 108 days, his body broken under the weight of relentless torture.

In another chilling plot, Swiss media uncovered a scheme involving two Turkish embassy officials who allegedly planned to drug and abduct a Swiss-Turkish businessman and smuggle him back to Turkey.

The plan was thwarted, but it revealed the extent to which Erdogan’s regime had cast its shadow, even over democratic states that were once considered safe havens for exiled Turkish nationals.

This week’s abductions in Nairobi have only heightened the fear that now grips Turkish exiles across the globe. They have come to realize that nowhere is truly beyond the reach of Erdogan’s regime.

But the burning question, one that even the Kenyan police have yet to answer, is this: Did a foreign state carry out these kidnappings on Kenyan soil?