Breaking News: Former Lugari MP Cyrus Jirongo dies in a road crash

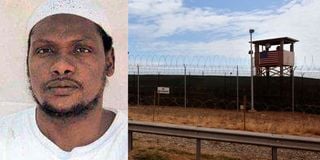

Kenyan national Mohamed Abdul-Malik Bajabu. Right: A guard tower at the Guantanamo detention center, at the US Naval Base, in Guantanamo Bay.

Mohamed Abdul-Malik Bajabu, a Kenyan, who has been detained at the US military base in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, for 17 years is now free.

The US Department of Defense announced Tuesday night the release of Mr Bajabu from the facility where US detained terror suspects following the 9/11 terrorist attack for which Al Qaeda claimed responsibility.

His release followed a decision by the USA’s Periodic Review Board (PRB), which unanimously resolved to return him to his home country.

His family has welcomed his release but requested time to organise their affairs before speaking to the media.

A family member who spoke to Nation.Africa on condition of anonymity due to sensitivity of the matter said they are grateful to the Kenya Kwanza government for its intervention.

The family source said, specifically, they appreciate efforts by President William Ruto and Foreign Affairs Cabinet Secretary Musalia Mudavadi.

However, the family asked that the media gives them time before more details about the way forward can be disclosed.

“The media has been with us throughout this journey. I cannot refuse to give you an interview, but please allow us to get some things in order. However, I will speak to the media,” a family member told Nation.Africa.

Guantanamo Bay was established in January 2002 by then US President George W. Bush to detain terrorism suspects and "illegal enemy combatants" as American forces waged the war on terrorism following the attacks of September 11, 2001.

The PRB is composed of six US federal agencies.

Established during the Barack Obama administration to determine the guilt of detainees at the facility, the PRB met in 2021 and decided to clear Mr Bajabu after concluding that he no longer posed a security threat to the US.

Bajabu was the only Kenyan captive held at the US military base, which is used to detain suspected militants and terrorists captured by US forces.

The prisoner rights group, Reprieve, has welcomed Bajabu’s release, stating that the transfer was long overdue.

“So we celebrate it with mixed emotions. We know from our Life After Guantánamo project that the mental scars of torture and indefinite detention can take many years to heal. The very least the US Government can do, having imprisoned Bajabu without trial for 17 years, is ensure that this is truly an end to his ordeal and the beginning of a new life with his family,” Reprieve’s Deputy Executive Director Dan Dolan said in a press statement to newsrooms.

Bajabu’s US legal team also celebrated his release from prison, stating he had been dreaming of this day for many years.

“We are overjoyed that he is finally back where he belongs, with his family in Kenya. The US robbed an innocent man of the best years of his life, separating him from his wife and young children when they most needed him,” said Frank Panopoulos,

“His children, infants when he was tortured, interrogated and shipped to Guantánamo, are now grown-ups. That debt can never be repaid, but the least the US can do is ensure that Abdulmalik receives the support and the space he needs to begin his life anew,” he added.

After closing this grim chapter of his life spent languishing in prison far from home, Bajabu now looks to forward to the embrace of his extensive family network in Kenya to rebuild his life.

This marks the end of nearly two decades of what Reprieve has described as an unjust and harrowing detention.

But how did Bajabu, a man born and raised in Kenya, find himself ensnared in a foreign prison, thousands of miles from the land of his birth?

The United States government accused Bajabu of associating with the Al-Qaeda terrorist group in East Africa and forging connections with its senior members.

He was further implicated in the planning and execution of the devastating terrorist attacks in Kenya’s coastal city of Mombasa in 2002.

Born in Kisumu in 1973, Bajabu’s early years were marked by misfortune.

Following the loss of their mother, he and his siblings were taken in by their elder half-sister in Mombasa, who assumed the role of guardian in a household shadowed by grief.

In pursuit of better opportunities, Bajabu left Kenya for Somalia in the mid-1990s, determined to provide for his family. There, he carved out a modest livelihood in the fishing industry and ran a small clothing shop.

Somalia also became the backdrop to the most significant chapter of his personal life, where he met and married the love of his life. Together, they were blessed with three daughters.

However, Bajabu’s time in Somalia was cut short by the eruption of conflict in late 2006, as tensions between Somalia and Ethiopia ignited a ferocious clash.

Forced to abandon his business and leave behind the life he had built, Bajabu fled back to Kenya, seeking solace and safety in his homeland.

Sadly, peace would remain elusive.

Two months later, in February 2007, Kenyan authorities arrested Bajabu in Mombasa. He was reportedly subjected to brutal torture before being handed over to US military personnel.

No evidence was ever produced- or at least made public- to substantiate his alleged crimes.

What ensued was a profoundly distressing ordeal. Bajabu endured interrogation and torture in clandestine US prisons in Djibouti and Afghanistan before being transferred to the infamous Guantánamo Bay in March 2007.

Like other detainees, Bajabu was detained in harsh conditions, which included extreme isolation, sensory deprivation, confinement in cages, and interrogation while shackled in excruciating positions.

It is also alleged that he endured sleep deprivation, exposure to extreme temperatures, beatings, threats, sexual humiliation, and denial of legal representation, which were part of the grim tapestry of his detention.

Reprieve has highlighted that much of the so-called “evidence” against Bajabu was extracted under duress, including testimony from a childhood friend who was himself subjected to torture by Kenyan and Ethiopian authorities.

This friend has since recanted his statements, casting further doubt on the integrity of the accusations.

Notably, the organisation states that all of Bajabu’s supposed co-conspirators have been acquitted by the Kenyan courts, reinforcing the growing belief that his prolonged detention was built on a foundation of unsubstantiated claims and coerced confessions.

As he steps into the sunlight of freedom, Bajabu must confront the grueling task of piecing together the fragments of a life interrupted at the most productive age, hoping that the support of his family will provide the needed shoulder to lean on.