Inside the life story of America’s first black woman on the Supreme Court

US Supreme Court Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson.

What you need to know:

- Ketanji Onyika Brown Jackson’s story begins with her parents’ civil-rights-era love story and their determination to instil pride, purpose and a deep connection to African heritage.

- Raised by resilient, hardworking parents in segregated Miami, she excelled academically, pursued law at Harvard and rose through the judiciary to become the first black woman on the US Supreme Court.

- Born in 1970 to parents shaped by the civil rights movement, Ketanji Brown Jackson grew up surrounded by strong Black educators, principled parents and a belief in justice.

Over one winter break at Kentucky State University, Johnny Brown ran into his basketball colleague Calvin, who was known as Sonnyboy. During their conversation, Johnny mentioned that he planned to transfer to North Carolina Central University and was looking for someone to help him type his application essay. Sonnyboy informed Johnny that his sister Ellery was an exceptional typist. Johnny contacted Ellery and the relationship between the two blossomed into a union.

They married in Miami, Florida, in August 1968, shortly after Martin Luther King Jr had been assassinated, and on September 14, 1970, the couple welcomed their first child in an era when racial discrimination, though no longer legally sanctioned, still shaped Black American life. Inspired by the civil rights movement, Johnny and Ellery Brown, through their relative Carolynn, named their daughter Ketanji Onyika, which means "lovely one" in the West African language of Igbo.

In her memoir Lovely One, Ketanji chronicles how her parents instilled a sense of pride in her African heritage. When she was a baby, they would dress her in mini dashikis and Kente fabrics, and style her hair into Afro puffs to cultivate her cultural history. From the first moment Ketanji became conscious of herself, she aspired to be as purposeful as her parents Johnny and Ellery Brown. Her parents were driven individuals whose core values rested on impact, influence and societal contribution. They had a fierce pride in the journey and legacy of black people. They instilled in her a love for justice.

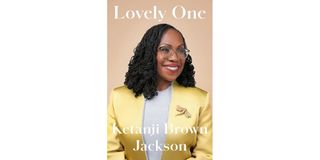

Ketanji Brown Jackson's memoir Lovely One.

For extended periods of her childhood, her mother was the family's sole breadwinner. She had majored in biology at Tuskegee University in Alabama and initially considered becoming a marine biologist. She would go on to teach middle and high school science and later served as principal of the prestigious New World School of the Arts in Miami, one of the premier high schools for the arts.

These were years when Ketanji's father, a former high school history teacher, toiled as one of a handful of black students at the University of Miami's law school. He was an ebony-skinned, gentle-voiced man who would look up from his textbooks to talk to her about litigation and ask for her four-year-old opinion. Ketanji first encountered her judicial calling in the tiny kitchen of their small family apartment at the far edge of the University of Miami's campus. She dreamt of resolving the dilemmas of individuals seeking legal recourse and drew inspiration from her father to study law.

The economic and life prospects of her parents' generation were significantly curtailed by laws designed to keep black people in subjugation and subordinate positions to Caucasians. The "separate but equal" laws limited black people’s access to workplaces, restaurants, theatres, hotels, transportation and other public goods and services that white citizens enjoyed. All of her teachers had been at the top of their classes and were remarkably gifted. Because none of them would be hired by white schools, they brought all of that talent and brilliance to children like Ketanji in black neighbourhoods.

Her parents instilled in her a belief in the power of individual grit and the tenacious quality of hard-headed optimism. This mentality propelled Ketanji to academic excellence. She graduated from Miami's Palmetto Senior High in 1988 as the student body president and national debate champion, and was voted “most likely to succeed”. She subsequently received a scholarship to Harvard, a prestigious institution of higher learning, to complete a Bachelor of Arts in Government. In 1992, after graduation, Ketanji enrolled at Harvard Law School, despite being derisively instructed by a lecturer to stop aiming so high.

In 1995, before the beginning of the autumn term of her second year of law school, she commenced her rigorous tenure as supervising editor of the illustrious Harvard Law Review. At a frantic pace, Ketanji administered the 76 members of the journal staff, stationed in Gannett House—the columned, multi-storey Greek Revival building that was the oldest surviving structure on the Harvard Law School campus.

She was acutely aware of being a Black law student, a status that reinforced her determination to develop a stronger work ethic than everyone around her.

Read: Timeline: The rise and fall of women's representation in Kenya’s political leadership since 2022

As she internally debated the intricacies of evidentiary rules and followed the arguments of the OJ Simpson trial on television, Ketanji came to a better understanding of how certain trial decisions were calculated. The Law Review experience elevated her pride in being among a century of the publication's staffers who eventually ascended to become leaders in society and law.

She graduated cum laude, which led to a series of US District clerkships. She served in the US District Court for the District of Massachusetts, moved to the US Court of Appeals, then was employed in four different private law firms from 1998 to 2010.

In 2013, then US President Barack Obama appointed Ketanji to the US District Court in Washington DC, and on June 17, 2021, President Joe Biden appointed her to the US Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit. On February 8, 2022, on a monumental occasion for black women, President Biden nominated her to the Supreme Court, and when she was confirmed by the Senate on April 7, she became America's first black female Supreme Court judge.

Ketanji sat on the same Supreme Court that had a century earlier enacted Jim Crow segregation, ruling that Black citizens “are so inferior and degraded that they could not be allowed to sit in public coaches occupied by white citizens”.

The author is a novelist, Big Brother Africa 2 Kenyan representative and founder of Jeff's Fitness Centre (@jeffbigbrother).