Breaking News: Former Lugari MP Cyrus Jirongo dies in a road crash

The day 27-year-old Tilam Leresh graduated into a Samburu moran was among the happiest times of his life, according to his family.

But the brave moran wouldn’t live long enough to enjoy this revered status in the community, raise a family and ultimately transition to an elder in his sunset years, as he would have hoped.

Instead, in the same fields that he spent most of his life, herding cattle and hunting down prey, his life would be brutally cut short by a trigger-happy British soldier.

Twelve years later, a court in Isiolo has fulfilled the family’s protracted quest to bring the moran’s killer to justice.

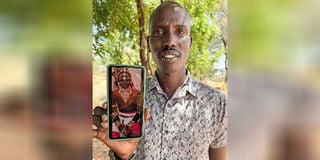

Clinging onto the only photo of Tilam adorned in the traditional Samburu attire, his brother Jacob Leresh recalls the fateful day that would envelop their family in gloom.

“My brother was shot dead while he was out grazing livestock. We found out about it when word spread through the community about a shooting incident,” Jacob recalls the sad incident. He spoke to Nation last week following the court verdict that ordered the prosecution of the British soldier for the murder of his brother.

It was the morning of Sunday, June 10, 2012. The search for greener pastures had taken Tilam and 12 of his friends into the vast Ol Kanjau area in Samburu.

What the group of morans didn’t know was that they had trespassed into a zone where soldiers from the British Army Training Unit Kenya (Batuk) were having a live fire exercise. Essentially, they had strayed into a restricted military zone.

“People in the community were not aware that it was a training area because there was no fence, demarcation or warning sign showing that it was an army training area. It was a piece of community land which the British soldiers had leased. There was a lack of communication to the locals many of whom are pastoralists and often went grazing into the land, particularly during the dry seasons,” says Jacob.

British Army soldiers board a military truck after a battle group exercise during a media engagement at the Lolldaiga training area in Laikipia County on November 14, 2022.

“The group of men who were with Leresh say they saw something that looked like a tiny aircraft observing them in the air. We later learnt that it was a drone. They were startled by it but went on grazing. Shortly thereafter, a helicopter began hovering over them,” Jacob recounts the accounts by Tilam’s friends.

Aboard the helicopter was Captain Richard Christopher Lynch who was on a surveillance mission to ensure the safety of 120 soldiers taking part in the exercise. The captain was with warrant officer Shaun Stewart as he flew around the training area to also ensure there were no civilians or animals within the range.

It’s in the course of the flight that they spotted six to eight civilians moving within the area at about 6am to 6.30 am.

Captain Christopher told the inquest the civilians were carrying “two G3 rifles and others which he did not recognise.”

Sergeant Brian George Maddison who was in charge of safety in the shooting range went in a Land Rover towards the area where the civilians had been spotted.

The low-flying helicopter jolted the group. The men fled in different directions. Witnesses say that everybody got far away from danger except Tilam.

Amidst the loud buzz of the helicopter, shots rang out. The crackle of gunfire echoed across the hot vast plains. Tilam lay dead.

Maddison had fired two rounds from an SA80 A2 rifle. A skilled arms instructor and a sniper trained to instructor level, his shots were on target and with deadly impact.

Maddison claimed he shot Tilam in self-defence. He alleged that Tilam pointed a G3 rifle at him and refused orders to lay down the weapon. This was his initial statement to authorities. He never testified in the subsequent inquest into the death of Tilam.

But witnesses disputed the British soldier’s claim. Moyalo Lesotia and Mokali Lorubat, who were with Tilam said the group of 12 fled when the low-flying helicopter swooped over them. The herdsmen said they never shot at the British soldiers and only realised that Tilam had been shot once they regrouped. The court eventually found Maddison had lied. Evidence produced during the hearing, including a post-mortem examination report, showed Tilam was shot in the back, as he ran away.

And the court uncovered an elaborate cover-up scheme by Batuk soldiers present at the scene, including obstructing Kenyan investigators. And it emerged the G3 rifle found at the scene had been stolen from a Kenyan police officer killed during a bandit attack 14 years earlier.

Major Doctor Guang Huayin from Batuk arrived at the scene to find Tilam, in a blood-stained khaki greenish jacket marked NYS, kanga shukas and akala shoes, lying in the thick dry grass. Guang, who testified from Birmingham, said he checked for a pulse and tried to resuscitate Tilam but he did not respond. He pronounced him dead. Maddison had the G3 rifle that had since been discharged for safety reasons.

According to court documents obtained exclusively by Nation, the murder weapon — a SA80 A2 rifle — had not been issued to Maddison. He introduced the name of another young soldier identified as Ranger Baird whom it would appear was holding the rifle. Maddison said he took the gun away from Baird because he was unsure of how the young soldier would react to the situation.

Maddison claimed he had a clear, unobstructed view of Tilam running towards him with a weapon. After his warnings to him to drop the gun were ignored, he fired two shots at Tilam, he alleged.

But his self-defence theory was deflated by evidence presented in court. The post-mortem examination on the body by Dr James Hussel from the United Kingdom showed the bullet hit Tilam in the back and exited through his chest. This meant he would have been facing away from Maddison when he was shot.

Katherine Ann Scott, a forensic scientist from the United Kingdom, also explained that, given the skill set of Sergeant Maddison, she would have expected one of the bullets he had fired to have hit Tilam on his front chest area if he was indeed facing the British soldier.

The fact that he had been struck on the back meant that other factors must have been at play. Scott added that Maddison had not provided an account in response to the findings.

In a twist, court records also state that the G3 rifle found lying next to Tilam’s body had been stolen from a police officer killed during a bandit attack in Moyale in 1998. Inspector Said Ilibae told the court the officer commanding station at Archers Post circulated information about the G3 rifle. Records at police headquarters revealed that the firearm had been issued to Moyale divisional police. Marsabit police disclosed the firearm was among two lost on April 4, 1998, during a raid by bandits in Moyale in which a police officer was killed.

Ilibae also testified that, when he and his team got to the scene of Tilam’s shooting, they were not allowed to go near the body or do any investigations. Ilibae said Batuk usually mark a shooting range with red ribbons but when he visited the scene he never saw such markings or a fence.

But a dogged determination by Tilam’s family in their relentless pursuit of the only people who could tell the other side of the story, Tilam’s friends who were with him during the shooting, kept the case alive. Once they had gathered the witnesses and recorded statements with the police, the case went to court.

Chief Inspector Maxwell Otieno of the Directorate of Criminal Investigations (DCI) headquarters who took over investigations testified that his colleague from DCI Samburu East, Said, informed him after the shooting that Batuk denied him (Said) access to the scene. Otieno said that, in the course of the investigations, they interviewed Maddison, who claimed he shot Tilam in self-defence but other witnesses disputed the narrative, saying, Tilam was not armed.

In the end, Chief Magistrate Lucy Mutai after the inquest found no evidence to demonstrate that Tilam had shot at Maddison hence rejecting his self-defence theory. On March 7, 2024, the magistrate recommended that Sergeant Maddison be arrested and charged with the murder of Tilam Leresh.

We reached out to the Head of Communications at the British High Commission regarding the case. In a statement the High Commission said: “The UK exercised criminal jurisdiction over the death of Tilam Leresh in 2012 in accordance with arrangements agreed with the Kenyan government. The UK Service Prosecuting Authority previously assessed that there was insufficient evidence to bring a charge against Sgt Maddison based on an alleged unlawful shooting. We are aware of the recent ruling by a Kenyan court.”

Jacob is still perplexed over the shooting: “There could not have been an argument that would have taken place between Tilam and Maddison because my brother had not been formally educated and mostly spoke in vernacular, while Maddison spoke fluent English.”

“The decision he made to shoot my brother brought so much devastation to our family. Had he not fired his weapon, my brother would still be alive,” Jacob adds.