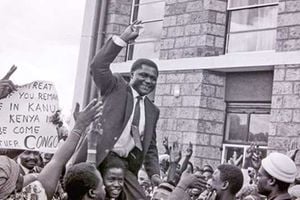

Civilians caught up in the attempted coup of August 1, 1982 walk on the streets while displaying their ID cards.

You are a very lucky man. I was about to open fire on you but something held me back,” a heavily armed soldier said in a rather friendly manner while looking at me straight in the face. I remained rooted to the spot, trembling.

According to him, I had just escaped death by a whisker. He looked at me, repeated the same words, adding, “I thought you were one of those rebels (of the Kenya Airforce).”

This was on Sunday August 1, 1982, inside the Voice of Kenya (VoK) studio during a shoot-out between rebel and loyal government soldiers. The rebels had attempted a coup to topple the then president, Daniel Arap Moi, from power. The man who had just spared my life was one of the loyal soldiers who had been battling with the mutineers.

A few years earlier, Daniel Moi had taken reins of power following the death of Kenya's first president Mzee Jomo Kenyatta on August 22, 1978, against the wishes of some in Kenyatta's government.

VoK would later be renamed Kenya Broadcasting Corporation (KBC). It has been many years since the incident occurred but the memories of that day are still fresh in my mind.

On the day’s eve, I was relaxing in the house after a busy week of gathering and disseminating news and other radio programmes. I was with my sister, Pauline, who was preparing to travel to Canada that evening at the invitation of our sister, Monica Zado, who was already living abroad with her Ugandan husband, Dr Joseph Galiwango. Pauline was very excited about the impending trip.

I drove her to Embakasi Airport in Nairobi – now known as Jomo Kenyatta International Airport, JKIA. We chatted and laughed a lot as we waited for her time to board. Travelling to the west was a great privilege those days. Rare as it was, it was desired by many. I envied Pauline as I watched her check in and leave for “the land of opportunity”.

At exactly 6pm, the plane carrying her took off. I watched in awe and waved as the aeroplane drifted into the sky until it disappeared in the clouds.

That evening, I chose to go home and spend time with my family instead of going out to catch up with friends as I occasionally did at the weekend. My three children; Ida, Jimmy and George, were then aged 16, 15 and three, respectively.

We spent the evening talking and playing, especially with my little three-year-old son who was the family’s centre of attraction, owing to his amusing childhood games and laughable attempts at speaking. He was all over the house, climbing on seats, rolling under the table, screaming for a toy, speaking inaudible words, as we all laughed.

Police officers guard looted property recovered from a lodging in Kirinyaga Road, Nairobi, following the failed coup attempt on August 1, 1982.

I was not scheduled to work on Sunday. So, I promised my wife and children that I would take them out after attending the Sunday service at St Stephen's ACK, Jogoo Road. We continued talking late into the night as my two big children narrated exciting stories until they dozed off. I retired to bed at around midnight.

At 4am, early Sunday, when virtually everyone in my neighbourhood in Ngara Estate, Nairobi, was still asleep, I was rudely awakened by a loud bang on my bedroom window. I first thought that burglars were breaking into our house. I sat up on the bed and listened keenly. The knocking continued – rough, repeated, and impatient – accompanied by shouting of my name.

“Mbotela! Leonard Mbotela! Where are you? Toka nje! Come out!”

Wait a minute, I thought. That is not how burglars behave.

The banging became intense. I thought they would break down the door. Full of fear, I switched on the lights and opened the door. I saw two military vehicles and several soldiers pacing around our compound.

Standing next to my door was a familiar face; Peter Wainaina, our VoK driver. Wainaina was a good friend of mine with whom I had worked with for over 10 years. He used to pick me very early in the morning whenever I was the one to open the radio station. Normally, he would arrive quietly and wait patiently at the parking lot. He was a courteous man and I loved how he conducted himself. In case he knocked on my door, he did it very gently.

However, it was all different that Sunday morning. I was not expecting him but there he was in the company of soldiers who were armed to their teeth.

Also Read: The six hours that changed Kenya in 1982

When our eyes met, a visibly shaken Wainaina mumbled a few words to the effect that the soldiers were looking for me. He was too scared to talk. He used more signs and gestures than words. I later learned that he had been captured at the VoK parking lot at gunpoint by the rebel soldiers, as he prepared to go round and pick the staff who were on duty that morning. The rebels had then ordered him to show them where I lived. They specifically told him that they wanted me.

Frightened, Wainaina had brought them to my house in Ngara Estate.

When I stepped out, the lead soldier approached me quickly and asked, “Are you Leonard Mambo Mbotela?”

His voice was loud and commanding. His face was mean. Trembling, I stammered, “Yes… yes, I am Leonard Mbotela.”

“You have one minute! Dress up immediately we go!” he ordered.

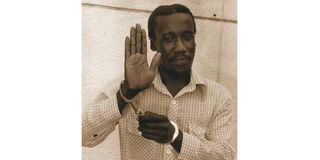

Senior Private Hezekiah Ochuka who was the ringleader of the attempted coup of 1982.

“Or we shall shoot you!” another soldier shouted.

Meanwhile, one of the soldiers fired into the air, twa! twa! twa! This further compounded my fears. Then another one shot directly on the wall of my house. The bullet did not penetrate through but ricocheted off the wall with sparks that scared me to death. The sounds woke up everyone in our house and the neighbourhood.

I rushed to my bedroom and dressed up quickly, unlike on other occasions. There was no time to choose a shirt and its marching tie and suit.

I told my wife that some heavily armed soldiers had come for me and I didn’t know where they were taking me. I knew I had been kidnapped.

“I’m not sure if I will come back alive, pray for me,” I told her as I hurriedly dressed and left the house.

She looked at me helplessly and I could see tears in her eyes. Ida and Jimmy were now awake, owing to the commotion. I peeped into their room and saw their innocent and frightened faces. I knew that was the last time I would see them. I hastily told them to continue sleeping, and not to worry.

I was quickly bundled into a military Land Rover and sandwiched by armed soldiers. The car was driven very fast and carelessly, often taking the wrong lane. I held onto my seat as the driver hit potholes and over speed bumps. We were thrown up and down. At every right turn, my body pushed heavily against the soldier in the passenger’s seat. At every left turn, I fell on the driver. It was the roughest ride I had ever experienced.

I was shocked to see the streets full of noisy soldiers. Most of them were visibly drunk, mainly from beer they had looted. They were walking around with beer bottles. Some students from the University of Nairobi, which is adjacent to VoK, had joined the melee. They were shouting “Power! Power! Power!” I still had no idea what was going on.

In a few minutes, we arrived at the VoK. I was ordered to switch on the radio. Everything was moving so fast. The soldiers were shouting orders incessantly. “Fanya haraka ama nikupige risasi!” (Hurry up or else I shoot you!) one of them threatened me. He seemed serious. I knew anything could happen here. I panicked.

I was bullied from all corners. Out of fear, my coordination became quite poor, but I managed to hurriedly do all that they ordered me to do. The team leader, who had come for me that morning, whom I later learned was Private Hezekiah Ochuka, handed me a piece of paper where he had scribbled a statement.

Civilians caught up in the attempted coup of August 1, 1982 walk on the streets while displaying their ID cards.

“Announce this! Tell the nation that Ochuka is the new president of Kenya. Moi is no longer president,” he ordered.

That is when it dawned on me that these army men had just overthrown Moi’s government.

Without hesitation, lest I got shot, I went live on-air announcing, “Dear listeners, dear Kenyans, this is VoK, my name is Leonard Mambo Mbotela. You are informed that the Government of Daniel Arap Moi has been overthrown… Yes, get it clear from me… the Government of Daniel Arap Moi has been overthrown. He is no longer the president of Kenya. The military is now in charge of the country. The police are now civilians. All prisoners are now free. Wananchi, you are ordered to remain wherever you are until you get further instructions. I’m here in the studio with the new Kenyan president, Hezekiah Ochuka…” I completed the announcement.

“Say it again!” Ochuka ordered and banged the table. Several soldiers had surrounded me. They celebrated violently and threw things all over as I mentioned that Ochuka was Kenya’s new President. I fearfully read the same statement over and over again. It was a moment of shock and apprehension to many people who listened to the radio that morning. Ochuka then took over the microphone and explained further the reasons why they had toppled Moi. He talked about the lack of political freedom in Kenya, among a host of other grievances. I recall hearing him promise that “Kenya is now going to be a very good country.”

He then selected his favourite Lingala music and asked me to play it repeatedly. He danced along with his fellow drunken soldiers. I am sure, in his mind, he was warming up to ascend to the high position of president of the Republic of Kenya.

The rebels had not just overrun VoK. They were all over the Nairobi Central Business District, killing, looting, vandalising property and harassing innocent people. Most of the shops that had glass windows had been shattered and plundered by the rebel soldiers and some fraudulent members of the public.

At about 8am, when it was slowly sinking in my mind that Moi had been overthrown, some rebel soldiers came running into the studio shouting, “We are being attacked by the loyal soldiers!”

Pandemonium ensued in my presence as Ochuka and other rebel soldiers ran for cover while shooting through the windows. Some fell over tables, scrambling for the exit as others jumped through the windows in a bid to escape. Ordinarily, one could be tempted to laugh; but this was not a laughing matter. Within seconds I was left alone in the studio. I switched off the radio. We remained off air for some time. I was confused. Do I run? Do I stay put?

I then heard deafening gunshots outside the studio. I was so scared. I could hardly move. My heart was throbbing fast. I crawled and hid under a table, and prayed. At that moment, the rebel and loyal soldiers were exchanging fierce gunfire around the VoK offices and its vicinity, which resulted in dozens of fatalities. I had been caught in a crossfire. I knew my fate was sealed; it would just be a matter of time before they came for me.

After a while, the gunshots stopped. This was followed by an eerie silence. Then, shortly, a tall military officer came into the studio. He was heavily armed with what I considered to be a very lethal gun. I do not have knowledge of firearms, so I cannot clearly describe it. He held his gun from the hip, ready to shoot. He looked like the commandos I had seen in movies. His bulging chest suggested he was wearing a bulletproof vest. My heart skipped a beat. I knew my end had come.

“Who is here? Come out! Surrender!” he shouted as he advanced.

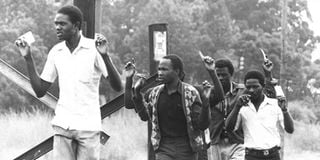

A Kenya Air Force rebel on top of a car addresses a crowd at Kariobangi Petrol Station on August 1, 1982.

I crawled from under the table, raised my hands and said, “My name is Leonard Mambo Mbotela, I work here at VoK. I’m a broadcaster… um… not a soldier.”

He was friendlier than the drunken and blood-thirsty soldiers I had interacted with earlier in the morning.

“Where are they?” he asked casually, his sharp eyes darting all over the studio, his gun held at the ready.

“They all ran away,” I replied.

Also Read: Musila - I saved Kibaki’s life, twice

He looked at me closely. He then continued sniffing virtually every corner looking for a sign of a rebel soldier. Having seen no enemy, he smiled and turned to me, “You are a very lucky man. I wanted to open fire at you but something held me back. I thought you were one of them (rebel soldiers).”

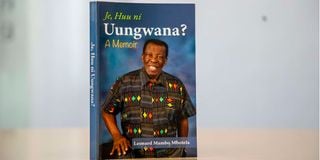

He then continued, “So you are the famous Mambo Mbotela! Wewe ni yule mtu wa Je Huu ni Uungwana? I always listen to you over the radio. I would easily have killed the person I have always admired and wished I could meet! It’s good I have met you today,” he spoke calmly.

He seemed to know me very well. He then walked out quickly. Unfortunately, I never got to meet this army officer ever again. Maybe one day, if he is still alive, and he reads this book, he may look for me and I would have the chance to tell him how thankful I am to him for sparing my life.

Within a short while, several soldiers walked in, followed by a senior military officer. His face was familiar. I had seen him several times during public functions like Jamhuri Day and Madaraka Day, where military parades were conducted. It was Major-General Mahmoud Mohamed, the Deputy Army Commander. General Jackson Mulinge was the Chief of General Staff (CGS) at that time.

Mahmoud was a visibly angry man. He looked at me with accusing eyes of “what-have-you-been-telling-the-nation?” He asked in Kiswahili, “Wewe Mbotela hiyo ni mambo gani ulikua unatangaza?” He did not even give me time to respond. Again, everything was moving pretty fast. He ordered me to retract the earlier announcement and inform the public that Moi was still the President of Kenya and that the coup plotters had been trounced.

“Do it very fast! Quickly! Quickly!” he shouted.

Also Read: How Moi brought down ‘traitor’ Njonjo

I obeyed his orders and hurriedly announced; “Dear listeners, dear Kenyans, good morning, this is Mambo Mbotela again … I want to make it clear that the earlier announcement that President Daniel Arap Moi had been overthrown was all lies. Yes, it was all lies. I repeat… it was all lies. The truth is that Moi is still the President of Kenya… You are advised to remain where you are but know that Moi is still the President of Kenya… Everything is under control. And everything remains as it was. Those who attempted to overthrow him have been defeated…”

Mahmoud nodded as I stressed the point that Moi was still the President of Kenya. “Say they have been killed...” he instructed. I repeated the sentence “Those who attempted to overthrow President Moi have been killed… and Moi is still in power.”

I then reinforced the same statement saying, “Hayo mambo ya kumuondoa Rais Moi kwenye mamlaka yalikua ni porojo tu!” (The coup report was propaganda).

Mahmoud nodded in appreciation. Suddenly, a little distant smile appeared on his face.

Leonard Mambo Mbotela’s book, ‘Je, Huu Ni Uungwana.’

Mahmoud wrote down the names of some of the notable senior loyal military officers who had accompanied him at VoK that morning. He told me to announce their names over the radio. I remember seeing Tom Wanambisi and Major Humphrey Njoroge, among others that I cannot recall. I read out their names on the radio and said they were some of the officers that were assisting Mahmoud in quelling the mutiny from different locations. I noticed that he was keen to note the military men who were for and against the coup. These pro-Moi soldiers that were at VoK that morning later rose through the military ranks to the level of Majors, Colonels and Brigadiers.

**

I later learned that Njoroge, reportedly based at the Department of Defence (DoD) at Hurlingham, after hearing of the coup reports from the radio, had driven to the precincts of VoK offices in an ambulance while dressed in a white lab coat, disguised as a doctor. He had spied on the rebels before going back to launch the attack.

He would later be aided by Wanambisi who led a team from Kahawa barracks, through Thika road, and attacked from the direction of the Museum hill to counter the rebels who were mainly stationed at VoK and other places within the city. In the ensuing combat, it was estimated that about 100 rebel soldiers were killed. That, I suspected, was the critical moment when the coup attempt was thwarted.

**

As the day progressed, more news came in from the loyal soldiers that the coup plotters had been defeated. Mahmoud became visibly happy.

He, however, asked me how I came to announce that Moi had been overthrown. It was a tough question.

“Sir, it was not my wish. I did it with a gun to my head,” I told him.

Read the first installment - Leonard Mambo Mbotela’s account of Tom Mboya’s death and 1969 Kisumu bloodbath - HERE

- Part three (Saturday December 23): Aftermath of the attempted coup and attending court martial

©Leonard Mambo Mbotela