Police officers guard looted property recovered from a lodging in Kirinyaga Road, Nairobi, following the failed coup attempt on August 1, 1982.

A dusk to dawn curfew was imposed in the country (after the August 1, 1982 coup attempt). This was the second nationwide curfew to be declared in Kenya with the first one having been during the Mau-Mau struggle for Independence in 1952.

The 1982 curfew was short. It lasted for only one month. When it began, many staff members at Voice of Kenya (VoK) were asked to remain at home due to security concerns and other logistical challenges. Only a handful of staff was allowed to work, mainly technicians (fundi wa mitambo). I was among them.

Soldiers would pick me from home every morning and drop me back in the evening. My main duty was to keep reiterating to the nation on the radio that Moi was still the President of Kenya.

Also Read: The six hours that changed Kenya in 1982

Occasionally, I read several news items that were brought to the studio by soldiers and some government officials. The prevailing conditions could not allow journalists to go out and gather news or have press conferences. We mainly announced news regarding ‘the good work of President Moi’ and ‘the ill-motives of the coup plotters who intended to bring down the country.’ Most content was brought to us from State House.

While in the studio, after short intervals of 10 minutes or so, I kept announcing that Moi was still the president of Kenya. Occasionally, I would play some music, mainly patriotic songs.

The song that I played repeatedly was Moi Songa na Mbele Tujenge Kenya Yetu by Joseph Kamaru. It was chosen deliberately to assure the nation that Moi was still in power and encourage people to have faith in him. It was a song of praise for Moi and his presidency as a symbol of national unity. This song, we believed, instilled hope to millions of Kenyans who were uncertain about the direction the country would take.

Tension was high in the country. People whose close family members, relatives and friends were reported missing were scared to death. It was chilling to imagine that a missing relative or friend could either be in prison, fighting for their lives in a hospital or in a morgue.

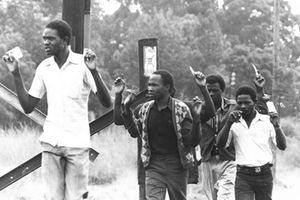

Civilians caught up in the attempted coup of August 1, 1982 walk on the streets while displaying their ID cards.

There was a lot of apprehension in all parts of the country as families mourned and buried their loved ones who had died in the attempted coup.

During this period, Mahmoud was a very busy man; moving all over to ensure that all was well. On the third day following the coup, Mahmoud came to the studio very early to assess what was going on. He stayed in the studio for a while, left in a hurry and returned after a short time. When he was convinced that all was well, he relaxed and even took me out for breakfast.

We sat at a table, sipping tea while holding a little casual talk. He looked very relaxed. For the first time since the coup, he talked about other things without mentioning it. He asked me to tell him about myself and where I came from. We chatted for about half an hour before going our separate ways.

Every cloud has a silver lining. It was due to the attempted coup that I got to know Mahmoud Mohammed. From there onwards we became very good friends. Later on, he would occasionally, buy me lunch at Nairobi’s high-end hotels and often tell the people we met, “Huyu Mbotela tuliteseka na yeye sana”, meaning that he and I went through a harrowing experience on that terrible Sunday morning of August 1, 1982.

VoK offices would be remembered as one of the combat zones during the coup. Several soldiers had been killed there. VoK was now considered a crime scene and became a highly guarded zone. A contingent of security personnel were positioned around this national broadcaster; it was now a no-go-zone. and the soldiers remained at the Broadcasting House for many years.

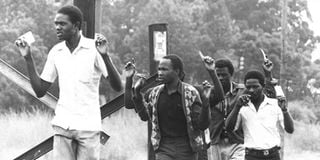

Scenes in Nairobi in August 1982, in the aftermath of the coup attempt. Police and soldiers subjected civilians to thorough security checks.

Most of the debris from the looting and the fighting in Nairobi had not been cleared. It took several weeks for normalcy to return. One could easily stumble on a body by the roadside or nearby plantations. In those days, the area between VoK and National Museums of Kenya, all the way down to Nairobi River was a thick bush. This was one of the combat zones and a number of soldiers were killed there.

Following the attempted coup, the suspected key mastermind, Private Hezekiah Ochuka, escaped to Tanzania using a Kenya Air Force plane. He left behind a team of vanquished mutineers who were either killed or arrested in large numbers.

Ochuka’s escape was short-lived. He was captured and detained by the Tanzanian authorities. He applied for political asylum while in Tanzania, arguing that he had escaped from Kenya due to political reasons and that his life was in danger. However, his plea was rejected by President Julius Nyerere’s government.

Back in Kenya, Moi’s government made spirited demands asking Tanzania to repatriate Ochuka so that he could face the law for his actions. Several months later, Ochuka was extradited to Kenya and charged with treason.

Ochuka was then arraigned before a court-martial sitting in Langata Barracks. This court was specifically set up to investigate the attempted coup and charge the mutineers and their collaborators. During Ochuka’s lengthy trial, I followed the proceeding keenly, both as a journalist and as an interested individual who was there when the attempted coup took place. All eyes at VoK were focused on these trials. About 80 percent of news at that time revolved around the ongoing cases against the mutineers.

Surprisingly, one day, I was summoned to appear before this court. I had been listed as one of the suspects, but I was never arrested. I just received a written summon that I appear before this court to ostensibly “explain my involvement in the attempted coup.” This was a shocking and chilling moment for me.

This was not a simple accusation. And the accusation was not before an ordinary court. This was a military court whose laws approved outright execution of a person found guilty of wrongdoing, especially on matters as grave as attempting to overthrow a president.

On the eve of appearing before this court, I was extremely worried. What if I was grouped among other suspects, detained or even executed? Anything was possible with the military, and, specifically, a rattled government. I was walking a very tight rope.

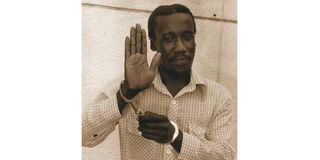

Soldiers patrol city streets after the coup attempt was crashed in 1982. Photo/FILE

I presented myself for interrogation early in the morning at exactly 7.34am on August 20, 1982 and was put in the dock on January 28, 1983. Ochuka, the main suspect was there. I had seen him earlier.

Yes, I now confirmed beyond doubt that he was the man who had come for me in my house at Ngara at 4am on that fateful Sunday morning of August 1, 1982. He was the same man who had sat with me in the front seat of that badly driven military Land Rover as we sped fast from my house in Ngara to VoK. He was the one who sat in the studio and gave me numerous directives as I announced that President Moi had been overthrown.

Now at the court-martial in Langata Barracks, I looked at him and our eyes met. This time he was subdued and miserable. He looked frail; a pale shadow of the confident and tough-talking man whom I had announced to be Kenya’s President.

He was accompanied by his lawyer, Moses Wetang’ula. The then Assistant Commissioner of Police, Awan Muskakeem Khan of CID Headquarters was present. Joginder Singh Sokhi was the Assistant Commissioner in-charge of investigations branch of CID headquarters, Nairobi.

I was tasked to explain the role I had played in the events of the early morning of Sunday August 1, 1982. The judge was a Caucasian called Peter Sidney Grey. Next to him were senior military officers. This judge had a strong commanding voice. I was asked to tell the court if the man in the dock (Ochuka) was the one who made me to make the announcement that Moi had been deposed. I answered in the affirmative.

“Are you very sure?” Judge Grey asked.

“Yes,” I said.

Senior Private Hezekiah Ochuka who was the ringleader of the attempted coup of 1982.

Grey then looked at me straight in the eye and asked, “What is your relationship with Ochuka? Do you know him personally?”

I told him I had never seen Ochuka before, until the day he came to my house to pick me.

“Why did he just choose you to make the coup announcement and not any other VoK reporter?”

That was a tough question. I never anticipated it and it indeed threw me off-guard. I remember fumbling to explain.

“Ochuka may have chosen me because I always run morning programmes.” And another very tough question followed, “How did he know where you stayed? And were you aware of his plans prior?”

The mean-looking judge asked me short and precise questions that demanded straight answers, in quick succession. Any ill-thought-out responses would have led one into incriminating themselves. I had to be careful. He wanted to know if I had met Ochuka or his people to work on a plan to overthrow the government. This implication made me sick because I knew I was not capable of and had never contemplated being part of such a treasonable act.

I decided to speak the truth candidly without any form of uncertainty, vagueness or ambiguity. I explained to the judge how I was taken from my house that morning and driven to the station at gun-point and that Ochuka and his team had kidnapped a VoK driver who showed them my house. I narrated the events of that morning and what I had heard the rebel soldiers talk about. I told the court that I had no prior knowledge of the planned coup. I was also cross-examined by lawyer Wetang’ula.

There was an awkward silence as the judge consulted with other members of the jury. I tried to put on a calm face but I was literally shaking. As the popular saying goes, be wary of a lion that has tasted blood. Grey, reputed for being a no-nonsense advocate and judge, had already sentenced several people to jail concerning this matter. I knew my freedom lay in his hands and there was a possibility I could land in prison if he did not buy into my story.

I was extremely relieved when he turned to me with what I thought was a smile and said, “You are innocent. This court finds you not guilty. You are free to go.” I hurriedly left Langata Barracks hoping they would not change their mind and call me back.

**

Meanwhile, a spirited crackdown on suspected coup plotters continued. Security forces were sniffing all over, arresting suspects. It was believed that the rebels worked with several other supporters, real or imagined, outside the military. Hundreds of suspects were hunted down, interrogated, tortured and even detained.

Politicians, businessmen, members of the civil society, lecturers and university students were among people that were linked to the coup. Perhaps that was the reason why the judge was interested in knowing if the media (in this case Mambo Mbotela) was also part of the wider syndicate that planned the coup. However, in the end, the media was not found culpable. Those days we had only one media outlet, the government-owned VoK and it could not have been easy to infiltrate it and conspire against the government from within. Perhaps things would have been different if we had many outlets and social media platforms as we do today.

Leonard Mambo Mbotela’s book, ‘Je, Huu Ni Uungwana.’

**

The 30-year-old Ochuka was eventually sentenced to death. I used to hear some people joke that he made history by becoming the shortest-serving President in the world, for only one hour. Others who were sentenced alongside Ochuka included Bramwell Njeremani, aged 27, Pancras Okumu and Walter Ojode. Most of them were very young people.

During trials, Ochuka’s team claimed that he had been given false promises of freedom if he made a confession and wrote an apology letter to President Moi. However, the military prosecution vehemently denied those allegations.

The Weekly Review, which was one of the reliable news outlets those days, reported in March 1984 that “The defending counsel for Ochuka, lawyer Wetang’ula, in his final submission before the passing of the sentence tried for four hours to convince the military court that his client had been cheated into confessing and had been subjected to inhuman condition while being held in prison.” But that did not alter the verdict of a death sentence. The die had been cast.

Lieutenant General Daniel Opande, in his autobiography, In Pursuit of Peace in Africa, indicates that Ochuka, alongside Pancras Okumu, was hanged on July 9, 1987. Opande writes: “In total, 12 rebel soldiers were sentenced to death, and hundreds jailed. Consequently, the Kenya Air Force was disbanded and, in its place, the 82 Air Force was formed. The present Kenya Air Force reverted to its old name after internal reforms and improvements were undertaken.” This came after it was established that the attempted coup was planned and executed by the Air Force alone without the knowledge of the other arms of the military, notably the army and the navy.

The saddest case was that of Major-General Peter Kariuki. General Kariuki was a high-ranking officer of the Air Force whom the martial court found was loyal to President Moi, and did not participate in the attempted coup, but was jailed for “failure to prevent the coup.” He was accused of what could be termed as “sleeping on the job” because the rebellion was mainly carried out by members of his regiment. Despite his spirited court battle, he was jailed for four years and was never given back his job in the military. He was also stripped of his rank. His case dominated the news for many years because he was the highest-ranking military man charged for the mutiny.

In his defence, Kariuki argued in court that he had become aware of the “plans to disrupt the government” as early as July 14, 1982. He claimed that he immediately reported the matter to his seniors for further investigations, but they never got back to him regarding their findings, implying that had he been part of the planned coup, he would not have revealed the rebellion details to higher authorities. After serving his sentence, and consequently being dismissed from the military, he lodged a complaint in court and was awarded damages but his attempts to have the damages settled dragged on for years.

Later, in my interactions with people close to power, I heard that the coup plans had been detected by the then intelligence Chief James Kanyotu. Kanyotu had even shared the information with President Moi on Friday evening before the coup and they had agreed to meet on Monday, August 2, 1982 to deliberate further and see what steps to take against the coup plotters. Unfortunately, they got time-barred. The rebels struck on Sunday, August 2, 1982, as a majority of the military were out of Nairobi for combat training in Turkana.

Read the first installment - Leonard Mambo Mbotela’s account of Tom Mboya’s death and 1969 Kisumu bloodbath - HERE

Read the second installment - Leonard Mambo Mbotela: Day I was caught in the middle of 1982 attempted coup - HERE

- Part Four (Sunday December 24): How murder of Leonard Mambo Mbotela’s uncle changed the country and their family. Plus, ‘the programme that made me famous.’

©Leonard Mambo Mbotela