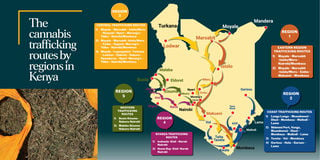

Despite the ongoing battle to ensure that bhang does not find its way into the country, some 22 routes linking Kenya to three of its neighbours continue to cause headaches for law enforcers.

The countries are Ethiopia, Tanzania and Uganda, with Ethiopia accounting for the highest number of routes – 11 – used to transport bhang into Kenya. This is followed by Uganda (seven) and then Tanzania, which has four routes.

This is according to the latest report from the National Crime Research Centre (NCRC), which shows that cannabis packages, often concealed to avoid police interception, are usually delivered to suppliers along the routes.

The survey also found that five regions—Eastern, Coast, Central, Nyanza and Western—offer better road networks for trafficking the drug, whose consumption has reached new highs in Kenya.

The two most popular destinations for bhang traffickers in the country are Nairobi and Mombasa, with the capital being the most lucrative, receiving the banned drug from at least 17 different routes.

The coastal city follows the capital, receiving bhang from 13 different routes.

The study found that the most common route used to smuggle bhang into Kenya from Ethiopia is Moyale, which is used in eight of the 11 routes used to transit the illegal drug. Bhang from Ethiopia is known as shash.

These routes include Ethiopia-Moyale-Mandera-Garissa and then finally to Mombasa. From Moyale, bhang is also usually transported to Marsabit, then to Isiolo, then to either Meru or Nairobi. There is also the Ethiopia-Moyale-Garissa-Thika-Nakuru/Nairobi/Mombasa route.

For a more widespread supply of the drug, traffickers opt for the Marsabit route as it allows them to use the Great North Road and/or Mandera to access Wajir, Garissa and finally Nairobi and Mombasa.

The report shows that traffickers prefer the Ethiopia-Moyale-Mandera-Garissa-Thika-Nairobi route at times, especially when the drug is in high demand and urgent.

Apart from Nairobi and Mombasa, Marsabit is also a good route for the drug to reach the hinterland of Lake Turkana, Lodwar and Kitale.

The other unique border route used is the Ethiopia-Forole route, where the drug is illegally transported to Kargi, then Wamba, then Marlan, then Nyahururu and finally Nairobi.

The other four routes are through Moyale, where several towns, including Brum, Shur, Marki, Isiolo, Maua, Meru and Thika, are supplied with bhang, which ends up in Nairobi and Mombasa.

For Tanzania, Migori is the most common route, accounting for six of the eight routes used for bhang trafficking. Muhuru Bay accounts for the remaining two routes. Bhang from Tanzania is known as 'bongo'.

These routes include Tanzania-Migori-Kisii-Narok-Ntulele-Mai Mahiu-Naivasha-Nairobi/Mombasa. There is also the Tanzania-Migori-Oyugis-Kisumu-Eldoret route.

The other common route is Tanzania-Migori-Kisii-Kericho-Nakuru-Naivasha and then Nairobi/Mombasa.

Muhuru Bay on Lake Victoria is most commonly used to bring bhang into Kenya via Migori, where it is taken to Rongo, Kisii, Narok, Naivasha and then either Nairobi or Mombasa.

For banange (Ugandan bhang) to find a safe landing in Kenya, the Busia and Malaba border posts prove to be the weakest links, accounting for six of the eight smuggling points.

The most common routes include Uganda-Busia/Malaba-Kisumu-Kericho-Nakuru-Nairobi-Southern Bypass-Mlolongo-Mombasa and Uganda-Busia/Malaba-Kisumu-Kericho-Nakuru-Mlolongo-Mariakani-Kilifi-Lamu.

More direct routes to Nairobi include Uganda-Malaba-Bungoma-Kiminini-Eldoret and Uganda-Busia/Malaba-Kisumu-Kericho-Nakuru-Nairobi, which usually extends to Mombasa.

Sio Port on Lake Victoria is often used to get banange to Kisumu, Kericho, Nakuru, Nairobi and Mombasa.

The other route is the Uganda-Migingo Island (Lake Victoria)-Mbita-Homa Bay-Kisii-Narok then Nairobi/Mombasa.

According to the NCRC, trafficking routes are not static, but change rapidly because traffickers are well connected and have "highly paid" informants who conduct security analyses and report back to them on the situation on the roads.

“Cannabis traffickers undertake risk assessments and employ sophisticated surveillance technologies and informers along the highways and roads,” part of the report reads.

“This facilitates easy movement of cannabis to evade law enforcement. This has seen police officers intensify their surveillance and sometimes erect impromptu roadblocks and checks on highways and feeder roads across the country.”

An analysis by the researchers of the factors driving the production, trafficking and sale of bhang in Kenya found that a growing culture of normalisation of cannabis use across the country and the widespread corruption among some law enforcement, regulatory and border management officials and national government administrators were largely to blame.

“Porous borders, high demand and availability of ready markets, higher monetary prospects and incentives and peer pressure factors, myths and misconceptions about cannabis were also highlighted,” reads the report.

Contrary to previous assumptions, bhang is not only used by people in poor neighbourhoods, and the study suggests that more innovative strategies are being used to transport, conceal and repurpose the drug to ensure it is not easily traceable.

Such is the rot among government officials that the NCRC found government vehicles being used to transport bhang.

There is also an increasing use of high-end vehicles -- Land Cruisers, Prados as well as Range Rovers -- to transport cannabis.

At times, matatus, buses, boats, motorcycles, as well as ambulances, hearses, cargo trucks, long-distance transport trucks, petroleum tankers, bicycles, hand and donkey carts, porters and courier parcels are used for the underworld business.

“Cannabis is often concealed in and among other goods and commodities such as second-hand clothes, spare motor vehicle parts, cereals (beans and maize), bread, fish, charcoal and cassava cargo. It is also hidden in fruits such as watermelons, pineapples and oranges being transported or under cold storage,” the report said.

Other traffickers sometimes use improvised compartments in some motor vehicles to transport bhang, with some even using perfumes and air fresheners to mask the drug's smell.

One subject in the study, identified as a former trafficker, confessed to his probation officer about how criminals use schoolgirls on school opening days to conceal and transport the drugs by hiding them in their school boxes.

“Nobody would suspect an innocent-looking schoolgirl to be transporting cannabis in her box. Once successful, the girl gets her cut,” the subject said.

This trend has occasionally led to the arrest of schoolchildren being used to transport and deliver bhang by police officers in the coastal region.

When it comes to the sale of bhang, there is no place left out, according to the research. Cannabis is sold in "offices, matatu and boda boda terminals, car wash bays, pool and video halls, car garages, construction sites, markets, mining sites, illicit alcohol dens, tuck shops and canteens around universities".

Coastal beaches, bars and restaurants also provide a safe haven for the trade.

But as ubiquitous as bhang may seem, not everyone can buy it from peddlers.

There is a specific vocabulary used by sellers and buyers to authenticate whether they are genuine dealers.

“We devise secret codes and nomenclatures around the sale of cannabis that are only known to close-knit customers and clients. I ordinarily will never sell weed (colloquial for bhang) to anybody who comes my way because he/she could be a police officer or an informer,” a convicted trafficker said.

The report also revealed that Malawi, whose bhang is known as GC (Golden Chocolate), and South Africa, whose cannabis is known as 'foreign' and has the highest value on the black market, also ship cannabis to Kenya.

There is also local or home-grown bhang, which is cleverly planted in agricultural plantations, forests and sometimes even in kitchen gardens, rooftops and fences of homes.

To effectively combat cannabis trafficking in the country, the NCRC recommends that the National Police Service and other security agencies intensify surveillance, intelligence gathering and information sharing to detect and disrupt emerging dynamics in the cannabis underworld.

The government, the National Authority for the Campaign Against Alcohol and Drugs Abuse (Nacada), government administration officers and civil societies should also partner and address the growing culture of normalisation of cannabis abuse due to various myths, misconceptions and disinformation.

The Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission, the report says, should address the endemic corruption among rogue law enforcement and administration officials who abet the production, trafficking, distribution, sale and use of cannabis.

The judiciary, meanwhile, should also develop mechanisms for the prompt disposal or destruction of cannabis exhibits, as storage of these exhibits poses a major challenge in most police stations, which lack adequate space and are tamper-proof, which could lead to their leakage into the black market.

It also wants the Interior ministry to devolve the services of the government chemist to the counties, as lack of access to the chemist has been identified by criminal justice stakeholders as a major challenge to the prosecution of cannabis-related offences.