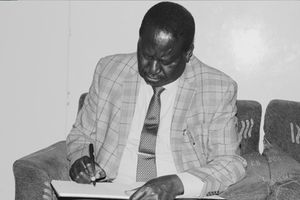

ODM party leader Raila Odinga carries a spear as he performs "Tero Buru" during the Luo tourism and cultural festival at Kenyatta Sports Ground in Kisumu on December 20, 2015.

On February 11, 2023, in the quiet village of Umiru in Siaya County, a chapter in Luo tradition quietly closed.

As the late Prof George Magoha, a towering academic and elder of rare stature, was laid to rest, one of the community’s most revered funeral rites, Tero Buru, was notably absent.

The ritual, once performed to cleanse death’s shadow from a homestead, had been omitted at the family's request. Bishop Martin Arara, the coordinator of the Gem Council of Elders, explained the family’s preference for a Christian send-off.

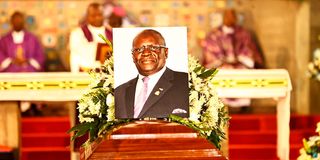

The casket bearing the remains of Prof George Magoha at Consolata Shrine in Nairobi on February 9, 2023.

“This is a Christian family. Since such traditional rituals are usually initiated by the family, and they have not done so, we will not be carrying out Tero Buru,” he stated.

His words signalled not merely a departure from custom, but the quiet erosion of a cultural pillar that once defined communal identity and spiritual order.

In generations past, Tero Buru , translated as “sending away the dust”, was one of the most dramatic and symbolically rich rituals in the Luo mourning tradition. Performed to ward off the malevolent spirit believed to cause death, it also restored spiritual harmony to the homestead.

At the death of an elder, the village would erupt in the thunder of hooves and ritual songs. Youths and elders, adorned in animal hides, sisal hats, and tyre sandals known as Akala, would drive bulls around the homestead, raising great clouds of dust, Buru, the rite’s namesake.

Accompanied by horns and drums, the mourners would escort the bulls to rivers or lakes, symbolic resting places for evil spirits. The charged procession was both cleansing and communal, a public outpouring of grief and defiance against death’s darkness.

Traditionally, the deceased’s eldest son would wear his father’s headgear, Ogut Dol, and wield his spear, Tong’ Dindo, stepping into the patriarch’s role in a sacred rite of succession. It was more than a gesture; it was a moment of inheritance, of duty, memory, and legacy.

ODM party leader Raila Odinga carries a spear as he performs "Tero Buru" during the Luo tourism and cultural festival at Kenyatta Sports Ground in Kisumu on December 20, 2015.

“The bull was driven inside the house of the bereaved. It could defecate and urinate there to symbolise mourning,” says Jotham Ajiki, organising secretary of the Luo Council of Elders.

Beyond their ritual role, the bulls embodied strength and pride, each movement echoing both farewell and unity.

Though modern life has diluted its grandeur, Tero Buru survives in symbolic forms across some Luo communities. Bulls may be replaced by songs and the rhythmic pulse of drums; horns still sound, carrying memory and meaning.

Cultural custodians suggest that the passing of monumental figures, such as the late Raila Odinga, may yet rekindle the full observance of Tero Buru, as a tribute not only to an individual, but to the cultural soul of a people.

Spiritual moment for the Luo nation

“Mr Odinga’s passing is not just a family loss; it is a cultural and spiritual moment for the Luo nation. If Tero Buru is performed, it will remind us of who we are and the values he stood for, such as courage, justice, and community,” said Mr Ajiki.

Ker Odungi Randa, chairman of the Luo Council of Elders, affirmed that the rite once safeguarded lineage and cohesion.

“The practice was about cleansing, transferring leadership, and ensuring that the clan remained whole,” he explained.

Another poignant ritual, Liedo - the shaving of heads - offered a visual expression of mourning. Four days after the burial, razors would scrape clean the heads of widows and children, later extending to other mourners.

The first shave marked the entry into mourning, the second released children from seclusion, and the third freed the widow from taboo, preparing her for Tero Chola — the inheritance rite.

“In the old days, you could hear the scrape of blades at dawn. Today, people do it once, if at all,” said John Akumu of Alego.

The mourning period, Budho, was marked by a deliberate slowness. Mourners would linger, grieving communally. Departures from the homestead were staggered - elders first, the youngest last - a ritual in itself, symbolising the gradual loosening of grief.

In time, married daughters (Wagoguni) would return bearing food. Their shared meal with the bereaved was not mere nourishment; it was a metaphor for continuity - a ceremonial invitation to life.

“‘Yao dhot’ means opening the door. It was about life continuing. Today, we may skip it or replace it with a church service,” explains Jane Owiti, a widow from Gem.

ODM party leader Raila Odinga carries a spear as he performs "Tero Buru" during the Luo tourism and cultural festival at Kenyatta Sports Ground in Kisumu on December 20, 2015.

Tero chola, in which a widow visits her natal home before rejoining her marital homestead under a new inheritor, remains one of the most debated practices. Traditionally, a goat would be slaughtered and its meat shared between her and her family.

But time, faith, and hardship have transformed these customs.

“Today, a majority of Luo are Christians, embracing a foreign culture that has profoundly impacted the preservation of our own heritage. The intrinsic value of our practices seems diminished, as many perceive Christian culture as superior and a mark of civilisation,” said Ker Odungi Randa.

Mr Ajiki notes that economic hardship has also played a part.

“Fifty years ago, life was different. People had land, food, and cattle. Today, many cannot afford these rituals since they’re struggling just to eat,” he noted.

Affine Omollo, a life coach, agrees. Shrinking cattle herds mean fewer families can afford the animals once central to Tero Buru.

“Today, most homes may have two or three cattle, a far cry from the 40 or more once typical in a Luo homestead,” he noted.

Even the late Prime Minister Raila Odinga, while championing culture, warned against burdening families with extravagant funerals.

“Lavish funerals push grieving families into poverty. That must stop,” he said at the 4th Annual Piny Luo Festival in Siaya.

He also reignited debate by urging the Luo to adopt male circumcision, a practice traditionally rejected, citing its medical benefits in HIV prevention.

The proposal met fierce resistance from elders who warned of misfortune and cultural loss.

Still, Mr Odinga remained firm, insisting that progress sometimes requires difficult breaks with tradition.