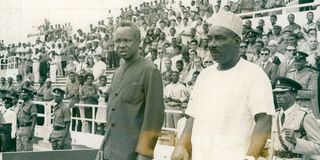

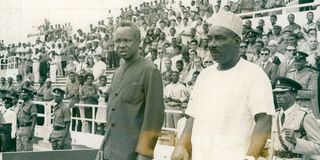

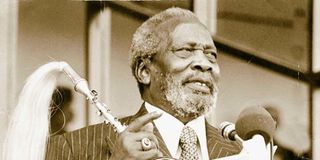

Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere with First Vice-President and Zanzibari President Sheikh Abeid Karume during celebrations marking the sixth anniversary of the island’s revolution.

AAA Ekirapa was a senior civil servant in the Office of the President when he received an unusual call. On the other end of the line was flamboyant “Field Marshal” John Okello, who had just led a revolution to overthrow the Sultan and the controversial Ugandan now wanted Jomo Kenyatta’s government to take over the island. The events that followed in Nairobi would have changed the map of East Africa were it not for an equally unusual reaction from State House. In the second of a three-part exclusive serialisation of Wings of Ambition – the memoir of a pioneer senior public servant, legendary corporate executive, businessman and politician – we revisit the surreal January 12, 1964 call.

A walk in the corridors of power is never bereft of drama and surprises. While working in the Office of the President, a call came in from Zanzibar on January 12, 1964. It was from Field Marshal John Gideon Okello.

Zanzibar had become independent about a month earlier, on December 10, 1963. His request was unusual.

“Look! I have overthrown the Sultanate of Zanzibar. But now, I don’t know what to do with this country. Can you come and take it over from me?” he said.

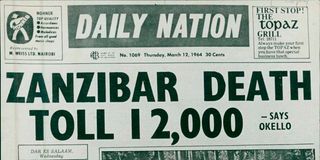

The Daily Nation’s headline on March 12, 1964.

To say we were surprised is an understatement; we were shocked! At the time, no one knew Field Marshal Okello. But after the call, news that the Sultan of Zanzibar, Jamshid bin Abdullah, had been overthrown started circulating.

The police and high-level intelligence officers put all the information together and convened a security meeting. In attendance were representatives from the Kenya Police Force (now service), the Armed Forces, Foreign Affairs Office, the Office of the President and other state agencies responsible for internal security.

When we got to the meeting, there was this officer – I don’t remember his rank – but he was the spokesman for the Kenya Police Force. He was intelligent and self -assured.

When we entered the room, we found he had already placed a large detailed map of Zanzibar on the table.

We then discussed the pros and cons of such a move. Every speaker argued in favour of an immediate takeover of Zanzibar by Kenya. Our discussion then shifted to the logistics of the takeover. The security officers explained to us the minimum force Kenya needed to use or deploy to take over Zanzibar from Field Marshall Okello.

He went straight to the purpose of the meeting: “There is a crisis that I would like us to discuss. We received a call from Field Marshal Okello saying he has overthrown the government of the Sultanate of Zanzibar. Before something happens, like may be, the Arabs mount a pushback in a bid to reclaim Zanzibar, Field Marshal Okello wants the Kenyan government to go to Zanzibar quickly and take over the country. The purpose of this meeting is to seek approval of this proposal.”

Besides that, he explained the economic benefits that would accrue for Kenya, if it warmed up to Field Marshal Okello’s invitation. He particularly reminded everyone about Zanzibar’s position in East Africa as a critical and attractive tourist destination. He wound up his presentation by taking a firm position – it was in Kenya’s best interest to take over Zanzibar.

The police had already outlined everything; how many General Service Unit (GSU) officers we needed to deploy there immediately, the number required for back-up and the number to be flown from Nanyuki by the Kenya Air Force.

At that juncture, Brig Joseph Ndolo, the then Kenya Army Commander, chipped in: “Look, if it becomes necessary, I will send in the Air Force!”

The Kenya Air Force, of course, was still a wing of the British Royal Air Force at that time. But that was neither here nor there to him. He was sure of the viability of the plan. We all were. Only one thing was remaining and we would be on our way – Prime Minister Jomo Kenyatta’s consent. We had done the planning without his knowledge.

So, we called the Minister for Defence, Dr Njoroge Mungai, to inform him. Aside from that, he was Kenyatta’s relative, physician and confidant. We explained everything to him – the developments in Zanzibar, our position on the matter and its implications for Kenya.

Dr Mungai cast his lot with us. He agreed that the Zanzibari revolution would no doubt excite the media and that we needed to win Kenyatta’s heart first. He had the Premier’s ear and so, we left the task of seeking consent from Kenyatta to him.

Dr Njoroge Mungai.

Dr Mungai went and explained everything to Mzee Kenyatta. Contrary to our expectations, Kenyatta just stared at him – as Dr Mungai would later report to us. The PM had said not a word – nothing! Since Dr Mungai did not get the answer he expected, he politely sought leave and said he would return the following morning. We thought it was the old man’s way of giving himself time to sleep it over and that he would give orders for our operation and Zanzibar would soon be ours.

When Dr Mungai went back to Gatundu the following morning, he was informed that Kenyatta had left for Nakuru.

During the entire time, our security officers had been waiting for the green light to pounce on Zanzibar. Common cadre officers were getting restless, yet their commanders couldn’t figure out what to tell them.

The senior commanders knew what was going on. That was the end of the story. Kenyatta never reverted to Dr Mungai on the matter. We, therefore, had no choice but to abandon our plan.

Nevertheless, I wonder what would have become of our history had Kenyatta approved of the invasion of Zanzibar. What would have been Tanganyika’s reaction? What about the East African Community (EAC)? Would our move have scuttled its formation and survival? Zanzibar later merged with Tanganyika on April 26, 1964 to form the United Republic of Tanzania.

***

But who was Field Marshal John Gideon Okello? I read up on his story and found it fascinating. John Okello came from a humble background, orphaned at the tender age of 11. He was born in a remote village in Lang’o sub-region of Alebtong District, northern Uganda.

At 15, he left home in search of a better life. He ended up doing factory and manual work in eastern Uganda, then Kenya and finally Zanzibar. He received military training while in Zanzibar. Thereafter, Okello joined the freedom struggle for the Black population there.

Africans had endured the autocratic Arab rule for centuries. It was a reign of terror that reduced the Black population to poverty-stricken subjects without any hope of governing themselves in their own land. Though most African countries had gained independence by the early 1960s, Arabs in Zanzibar were not willing to relinquish power.

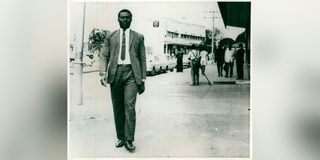

Field Marshal John Okello walks on the streets of Kampala.

In 1963, Okello started recruiting, training and rallying troops to battle the Arab rulers. His soldiers weren’t very well-equipped. They only had bows, arrows and a few guns.

This notwithstanding, Okello’s troops waged a successful nine-hour war against the Arabs. As a result of his defeat, the Sultan fled to England.

At only 27, Okello made an impact not only in his life, but also the political history of Zanzibar. After taking Stone Town, the capital of Zanzibar, Okello went live on Radio Zanzibar, declaring a change of guard and naming himself the Field Marshal of Zanzibar and Pemba.

In Idi Amin’s company

Unaware that the Sultan had fled, he ordered him over the radio to kill himself and his family. He warned that in the event the Sultan defied his order, he would have no choice but to execute it himself. Okello took control of Zanzibar and Pemba and formed the Revolutionary Council of Zanzibar.

Curiously, he decided not to become the leader of the island. Instead, he invited Sheikh Abeid Karume, an opposition leader whom Abdullah had exiled to mainland Tanganyika, to become president.

Upon Karume’s arrival, Okello received and introduced him to the people as their president. He did this on national radio.

***

Months into his presidency, Karume began to plot Okello’s removal. After making Karume the president of Zanzibar, Okello formed a paramilitary group called the Freedom Military Force to patrol and safeguard the island.

Accusations soon emerged that the outfit was terrorising people and looting. That, of course, was part of the conspiracy to demonise Okello and get rid of him. When Okello went on a trip outside Zanzibar, Karume labelled him an enemy of the state and on return, denied him entry to the island.

The plane carrying Okello wasn’t allowed to land in Zanzibar. It landed in Tanganyika instead.

Okello, a Ugandan born Christian, was only acceptable to the leaders of Zanzibar as long as he was useful to them. He had got them independence, so they were done with him. His popularity dwindled fast in the predominantly Muslim society.

That he spoke Kiswahili and English with a heavy and discernible Luo accent only validated his isolation.

Presidents Karume and Julius Nyerere of Tanganyika suspected that Okello was working against their political aspirations. They were persuaded that he was doing everything possible to bring about a merger between Kenya and Zanzibar.

Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere with First Vice-President and Zanzibari President Sheikh Abeid Karume during celebrations marking the sixth anniversary of the island’s revolution.

The two presidents were inclined towards a Zanzibar-Tanganyika union.

In his memoirs, Revolution in Zanzibar, Okello expresses awareness of these fears. He claims that President Nyerere was afraid he would unite Zanzibar with Kenya and not Tanganyika. That soon after Okello’s exit, Presidents Nyerere and Karume merged their countries to form Tanzania in 1964, lends credence to these argument.

The rejection of Okello by Zanzibar turned him into an “outcast” of sorts in East Africa. Tanganyika deported him to Kenya but he later left for Congo-Kinshasa, now the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Eventually, Okello moved back to Uganda when Idi Amin was serving the first year of his presidency. It is said that in his last public appearance, Okello was in the company of Amin. It is believed Amin considered him a competitor and commissioned his assassination.

Okello was a charismatic master of rhetoric who moved the people with his tongue. Among his many quotable quotes is the declaration that he would remain a Field Marshal to the end, notwithstanding whatever happened.

“...But I shall remain a Field Marshal dead or alive. If I die, God will make another man a Field Marshal who will work for the liberation of Africa!” he said.

Okello died in 1971.

Field Marshal Okello’s unexpected call and the fleeting opportunity for Kenya to take over Zanzibar unfurled a slew of lessons. This tale illuminates the unpredictable, often enigmatic nature of political developments. My role in this episode was peripheral, yet it unveiled insights into leadership and the intricacies of decision-making.

At its core, Okello’s actions represented a seismic shift in the power dynamics of Zanzibar, a territory he had wrested from the Sultan. The ensuing discussions presented an intriguing argument: the economic prospects of Kenya absorbing Zanzibar were undeniably appealing.

Mzee Jomo Kenyatta who in March 1963 was a minister in charge of Economic Planning.

The allure of Zanzibar’s tourism potential, its unique position in East Africa and the benefits for Kenya were hard to ignore. But the pivotal question lingered: “Would Mzee Jomo Kenyatta – our Prime Minister – sanction such a move?”

Kenyatta’s response speaks volumes about his leadership ethos and pragmatic compass. Rather than rushing into a decision with potentially far-reaching implications, he chose silence.

His inaction demonstrated that leadership is not solely about seizing advantages, but also judiciously weighing the political, strategic and even moral consequences. His silence underscored the importance of sobriety in decision-making.

At the same time, the story of Field Marshal John Okello offers a poignant narrative of forgotten heroes. Despite his pivotal role in Zanzibar’s journey to independence, Okello was discarded and exiled once his mission was complete.

His case is emblematic of a culture in which instrumental contributors are easily forgotten or even ostracised once their purpose diminishes. This reflects a broader societal issue where heroes are neglected, consigned to obscurity and their contributions fade into oblivion.

The story of Field Marshal John Okello and Kenya’s brief dalliance with the idea of annexing Zanzibar is fascinating and even funny in its absurdity. But that is always possible in the field of politics.

In the Sunday Nation: ‘How I transformed the Nation’