In his new book, AAA Ekirapa recalls his interactions with the first President of Kenya, Mzee Jomo Kenyatta.

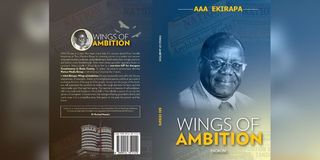

In this first of a three-part exclusive serialisation of Wings of Ambition, the memoir of Albert Aggrey Alexander (AAA) Ekirapa— a pioneer senior public servant, legendary corporate executive, businessman and politician — the author recalls his role in the tough transition from a colonial State, the dramatic death of freedom fighter General Baimunge, interactions with Jomo Kenyatta and the blatant land grabbing that followed independence.

After independence (in December 1963), I had barely settled down in my new role (in the Provincial Administration as District Officer 1 in Meru) when the Mau Mau fighters began coming out of the bush. My boss was very scared because to some people, the Mau Mau looked like wild animals. All their hair and eyes had changed colour. My boss left the station, never to return again to Meru.

So again, I took control of the entire Meru District. I became the acting DC *District Commissioner) because there was no DC. I had to deal with all the problems of the Mau Mau returnees. It was up to me to provide them with food and accommodation, among other necessities. Mzee Jomo Kenyatta (who later became the founding President) had just taken over as Prime Minister, but they were still learning how to run a government. There was nobody to hold my hand, so to speak.

Eventually, the Mau Mau story got to the Prime Minister, who asked to meet them in Nairobi. I was instructed by the PC (Provincial Commissioner) to facilitate their travel. Gachaiga, the local MP, saw the Mau Mau predicament as a chance for him to milk political capital. He took over the management of the situation. He told the fighters that he would take them to Mzee Kenyatta. In the end, after about ten days, I got a call from Nairobi.

The caller said that Mzee Kenyatta wanted to see me. The brief I received was that I should make arrangements to ferry the Mau Mau to Nairobi. So, I released a Land Rover. Of course, Gachaiga led the delegation.

When the people got to Nairobi, they were booked at the Gloria Hotel, which still stands today at the junction of Ronald Ngala and Tom Mboya streets. It was popular with Africans, then. The Mau Mau stayed there. They had no money, but they were accommodated. I do not remember who paid the bill. Maybe the government did. Ultimately, they went to see Mzee Kenyatta at State House, Nairobi. They told Kenyatta that they wanted to become generals in the army because they were already generals. They said that they had fought the British and beaten them and that it was only reasonable to let them assume leadership of the country.

Kenyatta was cunning. He told them: “That’s a good idea, but you see, we cannot do that because those generals in the army are trained. They are also soldiers. You are not trained, so, you cannot lead them. But I will do something for you.”

The cover page of the book Ekokom: Wings of Ambition, the memoir of Albert Aggrey Alexander (AAA) Ekirapa.

He told them that he would facilitate them to do business. That was how people like Kung’u Karumba (a freedom fighter) started the Wananchi Transport Company. In those days, transport business licensing fell in the docket of the DC. Karumba came back to Meru and told me: “Nice to see you in a position like this, or did we make a mistake to appoint you people?”

I told him they could not have made a mistake.

Then he said: “Anyway, Kenyatta has sent me to you. He says you give me a licence for transport for the whole country. He says I’m not educated enough to do something else. I can only do business.” So, I gave him a licence and he was very happy.

**

During this time, the Kenyatta government called on all the Mau Mau leaders who were still holed up in Mt Kenya Forest to come out of the bush and join other freedom fighters who had already disarmed. It was not easy getting the Mau Mau fighters out of the bush. Take, for example, the case of General Baimunge. He did not like the way his comrades had come out and received nothing in return for their contribution to the independence struggle. He expected that they would be made generals, but that was never to be. He was disillusioned because he was not quite sure what would happen to him because of his reluctance to surrender and come out of the forest.

Kenyatta had first sent Njoroge Mungai to go and tell these people to come out of the bush because they had now got their independence. Mungai even carried the Kenyan national flag. The Mau Mau fighters just looked at him and asked: “But who are you?”

“I am Njoroge Mungai. I am the Minister for Defence. I have been sent by Kenyatta,” he told them.

They told him they didn’t know who he was and if indeed Kenyatta wanted to send them somebody they could talk to, he should send them the son of Waiyaki, the heroic resistance leader who was killed by colonialists. So Kenyatta sent Waiyaki’s scion, Dr Munyua Waiyaki.

When they saw him, they asked him to prove that, indeed, it was him. They were convinced, and they came out of the bush – most of them. But General Baimunge was not among those who did.

Our Provincial Police Commissioner (PPC) was based in Isiolo. The PPC was a European called Oswald. He would come to Embu once a week for a meeting with the PC, Mr Eliud Mahihu, to brief him on matters of security. One morning after a meeting, Mahihu asked the PPC why, unlike his Mau Mau comrades, General Baimunge had declined to surrender and come out of the bush.

Baimunge’s death

From what the police knew, Oswald told Mahihu, Baimunge wasn’t sure what would happen to him if he did. Mahihu then asked if the police knew exactly where Baimunge was.

“Yes, we know precisely where he is,” Oswald said. “If you want me to bring him to you, I’ll go get him.”

Mahihu ordered Baimunge’s capture.

The next morning, when I got to the office, I got an “over over”, walkie talkie, report. It was from the PPC and it said thus: “The police made contact with General Baimunge. My instructor led the charge. They went there late when General Baimunge and his men were sleeping. General Baimunge had a system of security where he had people sleep all over the place, one here, another one there, about five guards before you could reach where he was sleeping. The police tip-toed into General Baimunge’s territory. They passed the first, second and third person. When the police reached the fourth man, one officer stepped on a dry leaf and it cracked. General Baimunge’s men jumped up and they saw a police inspector approach General Baimunge. They shot at the inspector and injured him. The police immediately returned fire and shot General Baimunge. He died. There was a bit of an exchange of fire as a result of which Baimunge’s men fled.”

I was shocked. In panic, I called Mahihu and told him: “Can you please come to the office quickly!” He came to the office, and I asked him to read the message. He did not know what to do because somehow, he was responsible for Baimunge’s death. He is the one who had instructed the PPC to go and get him. We panicked. That day, Jomo Kenyatta was going to Fort Hall (now Murang’a) for a public meeting. Tom Mboya was to accompany him. I thought fast.

“There is only one way out of this,” I advised Mahihu.

“Go and look for Mboya now before they start the meeting and explain to him what has happened. Let him speak to Kenyatta.”

That was what happened. Kenyatta, without really talking to Mahihu to find out what happened, told the people, “You know, we now have an African government which some people do not seem to recognise. One such a person is this so-called General Baimunge. He was asked to come out of the bush but he refused to comply. So, today, they had an encounter with my police officers. It was an unnecessary confrontation caused by his own stubbornness. He should not have died.”

That was the end of the General Baimunge story

**

From Meru, I was transferred to Embu and appointed the PA (Personal Assistant) to the Provincial Commissioner, Mr Eliud Mahihu. Mahihu was the PC for Eastern Province, with headquarters at Embu. He was from Nyeri, a colonial administrator and former home guard. I was used to doing a lot of office work. So, I enjoyed my new role. For a long time, I did not know that Mahihu was illiterate. I did not know that was the reason he always delegated all the office paperwork to me. Mahihu did not want to do any office work. He was always a field man. I would brief him about all the important happenings of the day, especially if these came from the Office of the President. Embu was not the first work station where I worked with Mahihu. I had previously worked with him in Kitale. From Kitale, he had, at the time, been posted to some place in Nakuru for special duties. Those special duties had something to do with the Kikuyu who had settled there. He was asked to move them elsewhere. Instead, he just killed most of them. He was in charge of the operation. I do not know what these Kikuyu did but most of them were killed.

After this operation, Mahihu was appointed PC. This was utterly dumbfounding. You go to your people and you do not know all things about them. But your first reaction is to have many of them killed by the police. Why would you kill your own people? What was the problem? Could you not arrest them and take them to court? I couldn’t understand it. But they made him PC. This could only mean that someone at the top knew what was going on.

Embu was a very engaging station for me. Politically, there was only one MP to work with. That was Jeremiah Nyaga, an Embu man who was disliked by the fewer Mbeere people who lived to the east of the district headquarters, Embu. The Mbeere complained that they were always getting a smaller bite of the cherry, while their counterparts from the Embu side benefited more and their MP favoured his Embu people. These fights continued for a long time until the Mbeere got their own constituency and MP, Silas Gaita.

**

After independence, the system of government changed, the opposition KADU joined KANU. Provinces became independent regional governments headed by a regional president. Suddenly, I found myself appointed to work for our government in Embu as the regional government assembly clerk. I worked for President Gaita of the Embu Regional Government. Some powerful elements in the central government were not quite comfortable with these arrangements. Jaramogi Oginga Odinga, the powerful KANU Vice President (and also National Vice President) and Minister for Home Affairs, was known to have been unhappy that the central, mainly KANU government, should cede some authority to the regions.

They were afraid that they would lose control of the whole country, especially the coastal region, which had always advocated for its own coastal administration to the extent of threatening secession. These efforts still come up periodically. But devolution has done much to quieten things.

Kenya's first Vice President Jaramogi Oginga Odinga.

One morning, we received a message from Jaramogi Oginga Odinga, the Minister for Home Affairs, saying, “Hii mambo ya Majimbo government, hakuna!” (“This business about regional government, there’s no such thing!) There is no president of Eastern Province or any other province. Hiyo kwisha. That’s over!”

Jaramogi had convinced Kenyatta to do away with that structure of government. He had told Kenyatta something the Prime Minister liked to hear: “How many presidents do we have in this country? You are the only president!” Kenyatta readily agreed. The regional governments reported to the Minister for Home Affairs. Jaramogi simply cut off all the financial support they received from the National government. With this, the governments died within the month as they could not pay staff or supplies for their offices. It was done by executive fiat.

**

As an Assistant Secretary at Harambee House (the office of the President), I would visit State House, Nairobi, many times, when it was necessary

in the line of duty. On each of my visits, I only had one mission – to have President (Jomo) Kenyatta append his signature on some land documents.

But President Kenyatta was rarely at State House. Throughout his fifteen-year rule, Kenyatta never spent a night at State House. He commuted from his village home in Gatundu. Speculation attributed his failure to spend a night in State House to his fear of ghosts. Kenyatta allegedly complained of hearing frogs croaking the whole night whenever he was at State House. In his imaginations, he construed the endless croaking of frogs as the white man’s protest over the war he had successfully waged against them. In their protest and expression of their discomfort with his presence at State House, the white men – Kenyatta believed – had transformed themselves into an orchestra of croaking frogs.

Kenyatta’s only recorded night at State House was in January 1969. This was occasioned by the death of CMG Argwings-Kodhek, then, a foremost lawyer and politician. When news broke out that Argwings-Kodhek had perished “in a road accident,” Kenyatta cut short his holiday in Mombasa and immediately returned to Nairobi. Those who were with him confirmed that that night he never slept a wink.

Albert Aggrey Alexander (AAA) Ekirapa presents his donation to President Daniel Arap Moi during a funds drive.

Another moment of historical significance further revealed President Kenyatta’s inclination to distance himself from State House. In the wake of Tom Mboya’s tragic assassination in July 1969, a crisis that sent shockwaves across the nation, Kenyatta convened an emergency cabinet meeting under a mango tree at his Gatundu residence, situated fifty kilometres from the bustling heart of Nairobi. Amidst the solemnity of the moment, beneath the natural canopy, decisions of great import were made. In the realm of power, where decisions shape destinies and symbolism is woven into the fabric of leadership, Kenyatta carved his own path. State House, though an emblem of authority, stood as a testament to the idiosyncrasies of a leader haunted by unseen ghosts, seeking solace in the embrace of his humble beginnings.

**

President Kenyatta was unpredictable and impulsive. Aside from his official car, he had a sports car gifted to him by an American friend. It was a top-of-the-range model for the Head of State. Curiously, Kenyatta never rode in the car. The only people I saw use the car were Ngengi Muigai and Udi Gecaga. And during Kenyatta’s funeral procession, I remember seeing Uhuru Kenyatta in the car.

Once I accompanied President Kenyatta to Ruring’u, Nyeri. Kenyatta used his official car, but the American sports car was in the entourage. During the visit, the driver of the sports car accidentally rammed into something and damaged it.

When the incident was reported to Kenyatta, he just hit the driver’s head with his walking stick!

As already noted, Duncan Ndegwa was my boss at Harambee House. One day, Ndegwa and I walked into President Jomo Kenyatta’s office at Harambee House. In my hands, I had a land allocation file. All the other relevant government officials had appended their signatures to the documents in the file. So we showed up before President Kenyatta for his signature – for the last word on the matter.

I must admit that all my life, I have always been an impatient and restless character. When President Kenyatta fixed his gaze on me, I must have given myself away. He must have sensed that I wanted him to promptly sign the documents and give me back the file.

“Who is this?” he asked Ndegwa in Gikuyu.

“His name is Ekirapa.” Ndegwa responded.

“Suppose I don’t sign these documents now, will the skies come down?”

“Your Excellency, No!” I answered.

“Baasi, alright, you go back to your office!” he said.

I promptly retreated to my office. The script that played out in that incident was quite familiar. President Kenyatta was deliberately buying time so that he could pick the brains of his Kiambu cronies. Such consultations informed his decision on whether to allocate a particular parcel of land to the specific person and not the other. And that was how Kenyatta’s Kiambu friends and government officials ended up owning prime pieces of lands in central Kenya and across the country. Many did not buy those pieces of land.

Kenya's first President Mzee Jomo Kenyatta.

During their occupation of Kenya, the British ejected the Agikuyu from their pieces of land and pushed them into concentration camps. In post-independence Kenya, the people applied to have the land the British had vacated revert to them. The people never got back their pieces of land.

This was because Kenyatta held the trump card on the land matter. He helped himself to huge tracts of land aside from inviting his allies to the land sharing party. Nobody got land in Kiambu without Kenyatta’s approval.

If you visited some of the former government officials from Kiambu, you would be amazed by the large tracts of land they own. Interestingly, if you went back to the records to see how they acquired these tracts of land, chances are high that you would find nothing. Zero records! These people acquired their riches from public land that Kenyatta gifted them. That is the truth.

**

One lesson I learnt from Kenyatta’s legacy was the importance of transparency and fairness in resource allocation. The land allocation process during his time was riddled with favouritism and corruption. He distributed land to his allies, often without a formal process and left little to no records of their acquisitions. This blatant disregard for due process in favour of political and tribal connections was a stark example of corruption and cronyism. Kenyatta’s actions in allocating land to his friends represent an early instance of the betrayal of the masses by the political class. It serves as a reminder that corruption within leadership can have far-reaching consequences, ultimately undermining the public’s trust in the government. My own experiences and observations throughout my career in public service, business and politics led me to detest corruption and cronyism.

**

In the Saturday Nation: How Kenya almost took over Zanzibar—until Jomo Kenyatta stopped the plan

© AAA Ekirapa