July 26,1988: Education minister Peter Oloo Aringo tables a report in Parliament by the Presidential Working Party on Education and Training for the Next Decade and Beyond set up by President Daniel Moi on August 27, 1985 with Mr James Mwangi Kamunge, a former director of education as its chairman. Permanent Secretary for Education Benjamin Kipkulei (centre) and director of Education James Waithaka were present.

In 1988, the government formally introduced cost-sharing in education that drastically reduced public funding for the sector through Sessional Paper No. 6 on Education and Manpower Training for the Next Decade and Beyond.

The policy paper decreed that parents and communities would, henceforth, provide teaching and learning resources to schools. Conversely, the government’s role was to provide teachers and quality assurance support.

The Sessional Paper gave legal backing to recommendations of the Presidential Working Party on Education, led by veteran educationist James Kamunge, and set the stage for their implementation. Popularly referred to as the Kamunge Report, the outcomes of that working party were to influence Kenya’s education for years.

Two years earlier, the government had published Sessional Paper No. 1 of 1986 on Economic Management for Renewed Growth, which recommended that the education budget be reduced to below 30 per cent of the recurrent expenditure. At the time, the education budget ranged between 35-37 per cent of the recurrent expenditure.

Based on the Sessional Paper, funding for education was progressively reduced from a high of 37 per cent to 25.4 per cent by 1995. And the results were devastating. Enrolments declined steeply, and the country started witnessing high cases of school dropouts.

Presidential Working Party on Education Reform Chairperson Prof Raphael Munavu addressing media during public hearings on education reforms held at the University of Nairobi (UoN) Taifa Hall on November 11, 2022.

According to the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics figures, gross primary school enrolments dropped from a high of 99 per cent in 1985 to 92 per cent in 1990 and then to 87 per cent in 1993. By the turn of the century, the country was recording a gross enrolment rate of 86 per cent, demonstrating a progressive high case of dropouts. In fact, the net enrolment rate, which refers to the actual number of learners of school-going age, was even lower, 75 per cent.

The rising cases of school dropouts became a matter of intense public debate in the 1990s, as Kenyans confronted the pains of cost-cutting strategies in the social sectors. Not only did this affect basic education, but it also hit universities, where the government withdrew subsidies and asked students to pay for their upkeep.

All this unfolded during a period of political turbulence marked by a shrinking democratic space and widespread violations of human and civil rights, and the consequential clamour for reforms.

Indeed, as the agitation for political and constitutional reforms began in earnest in the early 1990s, one of the rallying calls was the provision of education as a human right. This came to pass decades later with the promulgation of the 2010 Constitution, which, in Article 43, declares education as a human right. Concomitantly, Article 53 enjoins the government to offer free and compulsory basic education, which runs from pre-primary to secondary level.

Free education

In 2002, Kenya had a change of government. Narc, led by President Mwai Kibaki, ascended to power, ending the dictatorial 39-year Kanu rule, which started with founding President Jomo Kenyatta in 1963, followed by President Moi’s 24 years. In line with its manifesto, Narc declared primary education free and consequently ended years of cost-sharing that had locked out many children from school. Gross enrolments sharply rose from 86.9 per cent in 1999 to 102 per cent in 2003.

This historical background serves to contextualise the ongoing debate sparked by National Treasury Cabinet Secretary John Mbadi, who recently declared that the government can no longer fund primary and secondary education and accordingly called for the reintroduction of the cost-sharing policy in the education sector.

Former Education Minister Peter Oloo Aringo.

What Mr Mbadi advocated was a return to the pre-free primary education era, and accordingly, a signal to Kenyans that the government would no longer pay for learners’ tuition expenses in schools, leaving parents to their devices. Even though there were attempts to retract the comments and give the assurances that the funding would be retained, the reality is more complex.

Treasury Cabinet Secretary John Mbadi.

For starters, it must be acknowledged that Mr Mbadi was candid in admitting that the government cannot implement free primary and subsidised secondary education under the current economic and political conditions. However, he failed to address the reasons for the government’s inability to fulfil this constitutional obligation.

Evidently, the country is going through an economic crunch. But that is because of poor governance, failed policies, misdirected priorities, institutional decay, wanton mismanagement of public resources, and normalised corruption. The soaring debt burden and the high cost of repayment are all signs of fiscal indiscipline.

Provision of quality free and compulsory primary schooling and subsidised secondary education are constitutional imperatives. The Kenya Kwanza administration itself committed in its manifesto to providing universal basic education, which is defined in the Education Act, as 12 years of schooling. Failing to do so is not just an abrogation of constitutional rights but also an act of political deceit.

Given the state of things, the country needs an honest discussion on the state of education and the government’s capability to deliver it. President William Ruto, seeking to calm down a restive populace, declared last week that the government was not reneging on the universal basic education promise.

However, the question is: will the government allocate the requisite funds? Given its reputation for making lofty promises but poor delivery, can this administration be trusted to offer universal basic education?

Basic education

Yet, available evidence suggests that it is possible to provide universal basic education through strategic thinking, proper planning and political goodwill. Going forward, the government should consider the following to address the funding challenge.

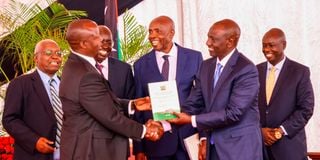

President William Ruto (right) presents a copy of the report by the Presidential Working Party on Education Reform to Julius Melly, the chair of the Education Committee of the National Assembly, flanked by Education CS Ezekiel Machogu (2nd right), PS Belio Kipsang and Prof Raphael Munavu (left) at State House, Nairobi.

First, the government should mop up and consolidate all education funds scattered across different entities and vote heads such as CDF, National Government Affirmative Action Fund (NGAAF), and others, and put them one basket to finance the education budget.

Second, the Education Ministry needs to review the secondary school fees and, for practical purposes, raise the figures from the current maximum of Sh53,000 to a realistic figure. This figure was set in 2014, and more than a decade later, it has been overtaken by inflation. Parents should then be asked to pay a percentage of the fees to supplement the government’s capitation. This should be done through a well-articulated policy paper and after public consultation.

Third, the responsibility of paying examination fees, which is a one-off expense, should revert to parents. The government’s decision to take over that payment was ill-advised since it did not have the resources to do so. Not surprisingly, there is always contestation in Parliament every year over the exam fee allocation earmarked for the Kenya National Examinations Council (Knec).

Fourth, the Auditor General should conduct an independent and countrywide audit to determine the correct number of schools in the country, with their physical location and enrolments. The recent findings by the Auditor General that the government was losing billions of cash through ghost schools was just the tip of an iceberg. The audit covered just a few schools and if the exercise could be expanded nationally, the findings would be alarming.

For Mr Mbadi and the entire administration, backing away from funding universal basic education is not an option. What is needed is clear budget prioritisation, efficient resource use, and unwavering accountability to ensure sustainability. Crucially, all policy decisions must be grounded in a strong legal framework — not in ad hoc pronouncements that only breed confusion and public frustration.

To be sure, in 2019, the former Education Cabinet Secretary, the late Prof George Magoha, appointed a task force to advise on the implementation of the Competence-Based Curriculum (CBC), and in the pursuit of its mandate, conducted an audit of existing schools – and the findings were shocking.

The country had tens of ghost schools, and the enrollments, for example, in primary schools, were fewer by more than one million learners, contrary to what had been predominantly stated. Consequently, Prof Magoha called for an overhaul of the National Education Management System (Nemis), declaring that it was flawed and unreliable. But that never happened. So, the rot persists.

Fifth, the government must prioritise spending and eliminate profligate spending across ministries and departments. It is unconscionable, for instance, for the National Treasury to allocate billions of cash for renovating the State House and lodges but fail to provide funds for schoolchildren. Neither does it make sense for top government officials to keep traversing the country for meaningless adventures like dishing out cash in the guise of economic empowerment when schools lack basic infrastructure and learning materials.

Since President Ruto has reaffirmed the government’s commitment to funding universal basic education, this pledge must now be matched by a revised budget allocation from the National Treasury. Compromising the education of Kenyan children because of fiscal mismanagement and political expediency is unacceptable.