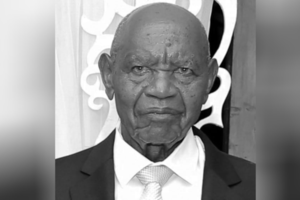

The Kapenguria Six. Seated: Kung’u Karumba, Jomo Kenyatta and Bildad Kaggia. Standing: Achieng Oneko, Fred Kubai and Paul Ngei.

Declassified files reveal how five of the imprisoned iconic independence heroes known as the Kapenguria Six were paid monthly fees and enjoyed a relatively comfortable but restricted life that would have made any African civil servant in the colonial service jealous.

Jomo Kenyatta, Kungu Karumba, Paul Ngei, Bildad Kaggia and Fred Kubai had been detained in Lodwar, then moved to a better restriction centre in the same region named Freetown after their transfer from Lokitaung Prison – which too also in Turkana.

Achieng' Oneko, the sixth detainee who was part of the Kapenguria trials, had been briefly held in Lokitaung before being transferred to Tarkwa Detention Camp on Manda Island.

For Kenyatta and the other four, the new conditions meant that apart from being allocated permanent family quarters, they had piped water, a doctor on standby, allowances and the privilege of living with their families.

The allowance was higher if one had a large family.

This followed a letter smuggled from Lokitaung Prison where Jomo Kenyatta and his co-accused had been incarcerated on allegations of organising and managing Mau Mau in a high-profile trial held in Kapenguria.

The letter – which was published in the London Observer newspaper on June 8, 1958 – the detainees complained about brutal treatment, poor sanitation, lack of clean water and the denial of visits by relatives.

The letter triggered hue and cry in the nationalist movement, with Tom Mboya introducing a motion in the Legislative Council on June 26, 1958, calling for an enquiry into the alleged ill-treatment of the five prisoners.

Contributing to the motion, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga, declared that the prisoners were the political leaders of Africans in Kenya and warned that if anything happened to them, the masses would take action.

Within the colonial government, apart from the intense pressure for the release of Kenyatta and his colleagues, there were fears that the inmates were attracting a lot of sympathy – making them “political martyrs” instead of “organisers of terrorism”.

To mitigate the situation, colonial Governor of Kenya, Sir Patrick Renison, formed a committee made up of senior civil servants to implement a systematic plan that would improve the welfare of the prisoners.

The team, which was domiciled at the Ministry of Defence, was made up of AC Small, the Under Secretary for Defence who served as chairman, Dr JH Taylor of the Medical Department, PG Garland of the Ministry of African Affairs, WRL Addison from the Treasury, DB Mills from the Ministry of Works EG Wright from the Kenya Police and WH Parkinson from the Special Branch (intelligence) headquarters.

Lt-Col HD Dent of the Ministry of Defence was the committee secretary.

After chairing the council of ministers in November 1958, Governor Renison directed the committee that “Kenyatta and his accomplices should be released from prison on licences to be at large, on 14 April 1959, subject to continued good behaviour; (b) Kenyatta and his accomplices should be restricted to a defined area in Lodwar which excludes the government quarters under effective control”.

To implement this directive, Mr Small and Lt Col Dent flew a reconnaissance mission over Lodwar and settled on an area later named Freetown, which they believed could serve as a restriction area for Kenyatta and his fellow inmates after their release from Lokitaung Prison. They were to enjoy some freedom but under close watch at Freetown.

The next order issued by the governor was that in preparation for the transfer of the five prisoners from Lokitaung for restriction in Lodwar, a doctor would be posted to the 40-bed Lodwar District Hospital.

To achieve this, the committee arranged for a Dr Patel to be transferred from Voi to Lodwar Hospital.

Because the hospital never had a qualified medical doctor for a long time, it was feared that posting one there after the transfer of Kenyatta and his fellow prisoners to Lodwar would create an impression among residents that the detainees were being given preferential treatment.

To avoid this, a decision was taken to post Dr Patel there around January 1959, three months before the arrival of Kenyatta and the other four members of the Kapenguria six.

Five suitable houses

The other directive issued by Sir Renison was about the accommodation of the detainees in readiness for their release from prison.

The colonial governor directed that discussions be held with the Treasury to provide funds for the construction of five suitable houses in Lodwar before the end of March 1959.

The houses were to be permanent and “built to the standard similar to the best African government quarter in Lodwar”. Piped water was also to be installed.

Regarding the furniture, the meeting of the committee held at the Ministry of Defence on December 4, 1958 took a decision.

“A bed, table and chair will be required for every quarter and the estimate mentioned above should include the provision for three items,” the committee agreed.

Minutes of the meeting marked “secret” went on: “Every restrictee occupying a quarter will be provided with a knife, fork, spoon, two plates, mug, two blankets, a lamp and two sufurias under arrangements to be made by the Ministry of Defence.”

The question of subsistence allowance turned out to be controversial.

Some representatives were of the opinion that Kenyatta and his colleagues, like others restrictees, “should be given a subsistence allowance adequate for themselves, and that if they want their wives and families to reside with them, should receive no extra allowance, but make their own arrangements”.

Other representatives argued that the five were in a different category.

Restriction

“First, because it was intended that their restriction should be for life and secondly, because their personal notoriety thrust them into the limelight to the extent that conditions of restriction would have to be defensible, probably in Parliament,” they said.

It was argued that if the six were not to be given enough money to maintain their families, then there was no point in building them married quarters and giving them permission to bring their families.

The eventual consensus was that Kenyatta and his fellow detainees be paid a single-rate allowance for themselves and an additional amount for one wife and every child who joined them.

“The amount paid to a man, his wife and two children should be about the same amount paid to an African government servant of medium seniority, such as the sergeant-major of Tribal Police (now Administration Police) or a sergeant prison warder,” they said.

According to the committee, that meant an allowance of Sh150 for a man, Sh50 for his wife and Sh25 for a child.

The five were to be given the option of buying their food or drawing government rations on payment at the prevailing rates.

Even though it was feared that the relatively high allowances Kenyatta and his colleagues were to earn could cause ill feeling among junior police officers, the committee argued that “they (police officers) had the compensation of not being restricted”.

On April 13, 1959, Kenyatta, Kaggia, Kubai, Ngei and Karumba were released from Lokitaung prison and moved to Freetown in Lodwar where they were to be restricted.

On arrival, they were allocated houses and told how much they would receive in cash.

“Kenyatta was to be paid Sh2,353.48, but there was to be an outstanding balance of Sh33.84 which was to be settled later. Kaggia was to receive Sh115.59, Kubai Sh104.89; Ngei Sh159.09 and Karumba Sh212.14. The miscellaneous receipts supporting these payments were signed by the five prisoners and counter-signed by the senior superintendent of prisons.

More freedom

After verifying the amount to be received, the cash was placed in envelopes and sealed as they watched. The envelopes were then taken to the District Commissioner’s office for safekeeping until the following morning.

Kenyatta remained in Freetown until 1961 when he was moved to Maralal where he enjoyed more freedom and lived a more comfortable life. He even complained about the quality of the window curtains installed by the government in his new house.

A bigger house was constructed for him by the colonial government, and unlike in Lodwar, he was allowed to move freely within the boundary of Maralal. He also had a police bodyguard and physician, Dr Carvallo, who had been the Medical Officer in charge at Eldoret District Hospital.

Dr Carvallo was transferred to Maralal Hospital specifically to serve as a physician to Kenyatta and his family. Kenyatta remained under restriction in Maralal until towards the end of 1961 when he was moved to Kiambu.

The colonial government built a magnificent house for him. In essence, he was a free man and the only thing he needed to do was report to the Kiambu District Commissioner once a week for a few months before he was fully set free.

The writer is a London-based Kenyan researcher and journalist