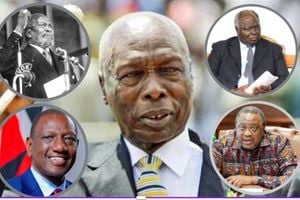

Daniel arap Moi, Mwai Kibaki, Njoroge Mungai and Jomo Kenyatta.

Once upon a time, in the heart of Nairobi, the prime plot at the junction of Kenyatta Avenue and Uhuru Highway was earmarked for a grand vision. The plan was simple yet ambitious: East African Airways, now moribund, would develop a sleek terminal facility alongside a luxury hotel.

The adjacent Barclays Plaza and Laico Regency included in the grand design. This was to be a gateway for travellers, where they could seamlessly book flights and enjoy the convenience of nearby accommodation — all in one space. It was a vision meant to blend profitability with visitor convenience, promising to elevate the airline’s prestige.

But then, as is so often the case in tales of ambition and opportunity, the vultures circled. Shadowy cartels, and politicos, with an eye for profit and a disregard for the common good, moved in. What was to be a promising venture opened space for backdoor deals as crooked hands quietly dismantled the dream and sought to own the project. If you have heard the story of Gautam Adani, and his quest to privatise the Jomo Kenyatta International Airport, this story will ring a bell. Politicians are always eyeing such grand projects and bringing in international businessmen to mask their interests. It becomes hard to know the faces behind the project within the layers of masks.

The story takes a new twist in 1970s, after East African Airways found itself in financial peril. As rumours of a possible collapse grew, so did the company's liquidity troubles. In March 1971, Mr SB Ogembo, the Permanent Secretary in the Ministry of Power and Communication, voiced the government's growing frustration with the airline’s failure to develop the critical Nairobi site. What Ogembo did not know — or perhaps he knew — was that he was setting the stage for the take-over of the prime plot. After all, there would be in the record a letter reminding EAA that they had failed to develop the plot allocated to them.

Interestingly, this letter sparked the interest of powerful figures — both political titans and financial magnates — whose ambitions were as grand as the plot itself. Among the key players circling the plot were Cabinet ministers Mwai Kibaki, Daniel arap Moi, Dr Njoroge Mungai, Odongo Omamo, Mathews Ogutu, and the mining magnate Tiny Rowland.

It is not clear whether President Kenyatta also had interest in the same plot but there is a letter dated August 1972, to the Commissioner of Lands, inquiring about available plots for hotel development in Nairobi. In his reply, Commissioner AJ O’Loughlin identified two prime plots — one reserved for a hotel, and another set aside since 1969 for the new East African Airways terminal. Kenyatta was told that the Kenya Tourist Development Corporation had also indicated that it wanted a share in the new development and had started scouting for investors. Also, the ministry of Finance and Planning, under Mwai Kibaki, had started discussions with various entrepreneurs such as Holiday Inn to develop the site. What the Commissioner of Lands never told Kenyatta was that his Cabinet ministers were pushing for some foreign interests and that they had formed companies to partner with any of the targeted companies.

Secret ambitions

So, unbeknownst to Kenyatta, members of his own Cabinet harboured secret ambitions. They quietly formed companies to compete for these lucrative plots, aligning themselves with foreign interests in a bid to secure these coveted lands. To maintain discretion, the Commissioner of Lands, O’Loughlin, proposed to Kenyatta that the terminal and hotel be developed as a single complex. “We must go for the hotel development soon in order to sterilise the site indefinitely,” O’Loughlin told the President. His plan, included government ownership alongside international hotel brands, aimed to boost the project’s profitability.

Kenyatta ordered that the land should not be advertised. Instead, he instructed O’Loughlin to privately gather proposals, ensuring only a select few would be privy to the opportunity. The game was afoot, and only those in Kenyatta’s trusted inner circle had the advantage. That is how deals were cut.

Private asset

The first proposal arrived from two businessmen, a Mr M Muhoho and Mr D Karanga, under the banner of Longwe and Company. In their proposals, they envisioned a grand 500-bed luxury hotel in collaboration with Sheraton International. However, their bid soon floundered when it became apparent, they lacked the capital. A second bid, championed by Kibaki, was through his Tubogo Consolidated Holdings Limited. It proposed a 600-bed first-class hotel. But even this, too, was flawed — their clever tactic was to use the plot as collateral to raise funds, transforming public land into a private asset.

There is in the file a separate bid from former Vice President Joe Murumbi who had a Special Purpose Vehicle, Grand Hotels Limited. His proposal collapsed when financial backers withdrew. Defense Minister Dr Njoroge Mungai’s came with his group but he encountered resistance from KTDC. Tourism Minister Mathews Ogutu and Odongo Omamo, hiding behind a company called International Business Representatives (EA) Limited, had secured French backing, only to face similar setbacks.

As the intrigue thickened, new actors entered the fray. In October 1973, Udi Gecaga, Kenyatta’s son-in-law and East African representative of Tiny Rowland’s notorious Lonhro empire, put forth an audacious proposal to develop prime real estate along University Way, Kenyatta Avenue, and Uhuru Highway. Lonhro, already notorious for securing advantageous deals with African leaders, drew wary glances.

Though backed by Nairobi’s Town Clerk, JP Mbogua, some government officials voiced misgivings, cautioning against ceding too much prime city land to a single entity. Gecaga’s ambitions were unmistakable: he sought to establish a sprawling property empire, with Lonhro holding a 49 per cent stake, the remainder distributed among Kenyan citizens. His vision attracted powerful allies, among them Andrew Ligale, Director of Physical Planning, who enthusiastically endorsed high-rise developments for the site.

Yet, in January 1974, Commissioner O’Loughlin delivered a blow by recommending the rejection of Lonhro’s bid, triggering a political deadlock. At the same time, Vice President Moi made a separate move to secure land for a Japanese firm, casting the entire project into uncertainty. As these factions wrestled over the prized plots, Kenyatta’s sudden demise left the final decision in the hands of his successor, Daniel arap Moi. Amid the chaos, Special Branch chief James Kanyotu secured a plot near the contested land to construct his agency’s headquarters, Nyati House, having previously been housed in Dr Mungai’s Queensway House along University Way.

Ultimately, it was Mohammed Aslam, a well-connected banker with ties to State House, who claimed part of the coveted land to develop what would become the Grand Regency Hotel. However, the saga spiraled further when Aslam’s Uhuru Highway Development Limited fell into the clutches of Kamlesh Pattni. What had begun as a project for the defunct East African Airways had become enmeshed in a web of competing interests, and even Kenya Airways, the airline’s successor, failed to secure the land.

In the end, the parcel was sold to the National Social Security Fund (NSSF), after being dubiously “allocated” to shadowy figures. NSSF later sold it to Indian businessman Ambani — who discovered that the land size listed on the title deed differed from the actual plot. He took the matter to court. If these tales seem familiar, it is because, despite the passage of time, history has a curious way of repeating itself. And so, good morning, State House.

@Johnkamau1