A British Chargé d’Affaires secretly recorded a conversation with the young Oburu in 1964 in Peking to assess the ideological leanings of Jaramogi Oginga Odinga's heir.

Oburu Oginga, who now takes charge of the Odinga political dynasty following the death of his brother Raila Odinga, was viewed as a future influential figure in Kenyan politics as early as 1961 when he was only a teenager.

His father, who saw him as an heir, exposed him to world politics and liberation politics quite early. According to documents intercepted by the British spy agency MI5 in 1961, he contemplated sending him to a private boys’ school in London’s upmarket suburb of Chelsea to give him international exposure and a solid educational foundation after he was denied a chance at Alliance.

Senator Oburu Odinga during former Prime Minister Raila Odinga's funeral service at Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology in Bondo, Siaya County on October 19, 2025.

Being the son of a leading Kenyan nationalist who was perceived to be pro-East, Oburu was treated as nobility when he visited China as a 20-year-old. One Western diplomat, after secretly recording a conversation with him in 1964, informed the Foreign Office in London that “Oburu Oginga may well one day be a man of some consequence in Kenya.”

Born in 1944 at Maseno, Oburu shares many traits with his father, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga. A straight talker and a man of disarming customary candour, he never conceals his views, no matter how inelegant they sound to his audience.

As a personality, he is easily accessible and keeps in close contact with ordinary people. Being the firstborn, Jaramogi definitely envisioned him as his heir who would one day take up his political mantle and lead his dynasty.

In 1961, at a time when many adults had not set foot in the capital Nairobi, Jaramogi was already contemplating enrolling Oburu at the London Academy, a private independent boys’ boarding school in London, after Alliance High School denied him admission.

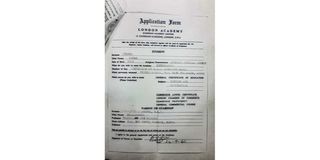

The school was first established in Switzerland in 1949 before opening a branch in London at Cadogan Gardens. A trove of Odinga’s correspondence intercepted by MI5 included an application form, a postal order worth £5 as a registration fee, and a letter to the school by Odinga.

In the application form, Oburu’s denomination was given as African Anglican Church, ‘parent’s profession’ as politician and businessman, ‘where previously educated’ as Pe-Hill School, and duration of stay as until completion of GCE Advanced Level.

Jaramogi Oginga Odinga attempted to enroll the teenage Oburu at a private boys' boarding school in London's Chelsea in 1961.

The form was signed by parent/guardian Jaramogi Oginga Odinga, who agreed to the general regulations and terms of the academy, and dated September 24, 1961. Since a registration fee of £5 was to accompany the form, Odinga bought a postal order worth the amount and enclosed it in an envelope alongside the application form and a letter stating: “Oburu Oginga’s form + £5.00 BPO is enclosed. The other form will follow later.”

Oburu, however, never joined the academy but instead left for Moscow via Cairo and London for his higher education. According to MI5 declassified records, he arrived in London on 11 February 1962 together with his father, who was a delegate to the second Lancaster Constitutional Conference.

They were both travelling on Ghanaian Passport No 1061, issued at the Ghana High Commission in London on December 12, 1961. Also with them on the same Air India flight (AI 115) from Cairo to London was businessman and politician Dickson Oruko Makasembo, who later became senator for Central Nyanza on June 1, 1963, but died two years later in a road accident.

Kenya's first Vice President Jaramogi Oginga Odinga.

On March 8, 1962, as Odinga became immersed in constitution-making at Lancaster House where a debate on the system of government had stalled the process, Oburu, in the company of Achieng Oneko’s son, bid him goodbye and left for Moscow for further studies aboard Aeroflot flight SU 032. Accompanying them as their guide was William Odhiambo Okello, who was travelling on Egyptian Passport No 1318. Okello had fled Kenya for Egypt in the 1950s and established the Kenya Office Cairo to agitate for the freedom of the African continent. He later moved to London where he continued to assist Jaramogi to channel students to educational institutions behind the Iron Curtain by way of Cairo and London.

In the USSR, Oburu joined the Soviet Secondary School in Moscow for his higher education, which he finished in 1964. On July 10, 1964, as he prepared to join People’s Friendship University for his bachelor’s degree, he was invited by the All-China Students’ Federation to tour China.

During the trip, he also held a meeting with Liao Chengzhi, Chairman of the Chinese Committee for Afro-Asian Solidarity and a member of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party. Chengzhi was the son of the Chinese statesman and revolutionary Liao Zhongkai.

On July 18, 1964, just a day before he left Beijing for Shanghai, he attended a dance hosted by Ambassador Simon Thuo Kairo at the Kenyan Embassy. As he danced the evening away, one of the guests pulled him aside and engaged him in a conversation that lasted slightly over an hour. This unusual partygoer was T. J. B. George, the British Chargé d’Affaires in Peking, now known as Beijing.

For the unsuspecting Oburu, who was not even aware that every word he uttered was being recorded, the conversation possibly passed for inconsequential chit-chat. For the British diplomat, however, it was a rare opportunity to understand the ideological orientation of a scion of one of Kenya’s most consequential nationalists of that time and to get his views on issues that could affect British interests.

“Our talk was fairly far-ranging and on the whole circular in argument,” the diplomat informed the Far Eastern Department at the Foreign Office in London. He also informed his seniors that, based on his assessment, Oburu appeared to favour the Russian brand of socialism, but added that the best part of their conversation was on the problems facing Kenya, especially on the question of land.

In this regard, he wrote: “He was quite adamant that the final solution lay in some form of nationalisation of the land, although he accepted that the present system would have to be tolerated until skilled people had been trained to take over from those whose goodwill Kenya could not afford to lose. He insured himself here against a possible charge of being anti-white.”

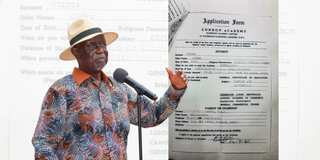

Oburu Oginga at a past event.

Although Oburu admitted during the discussion that the land usage system that existed in Kenya at that time worked, and that other means, other than state ownership, could furnish the capital to open up new land and provide more jobs, he was categorical that land reforms were the only way to satisfy the land hunger among the peasants.

The diplomat then brought up a discussion on the general merits and demerits of socialism, but just when Oburu had launched himself on the topic of what he termed as the “bloody war which the United States was waging in South Vietnam”, someone called him and he left the diplomat hanging.

In a report marked confidential sent to the Foreign Office in London, and also copied to the British Chancery in Moscow and the British Embassy in Nairobi, the diplomat stated: “Oburu struck me as being a decent but impressionable person, who had not yet fully thought out the implications of the philosophy which he has chosen to follow (although he could give me no really good account of why he had made the choice). His tendency was to follow any argument until he found it clashed with his beliefs and then to revert to dogma. I am afraid that three more years of his course on economic planning in Russia may put the kibosh on keeping his mind open.” To justify his reason for recording his conversation with Oburu, he explained: “I record the above merely because I suppose that Oburu Oginga may well one day be a man of some consequence in Kenya.”

After the trip, Oburu returned to Moscow to pursue his bachelor’s degree and later his master’s and PhD at Friendship University in Moscow. The institution was established in 1960 to meet the education needs of students from the Third World while also fulfilling USSR global goals. Its aim was to educate a Soviet-friendly intelligentsia and to foster a Soviet–Third World alliance.

He returned to Kenya in the early 1970s and tried a hand in elective politics in 1974, becoming a councillor in Kisumu. However, this early political adventure lasted for only five years, after which he joined the civil service as an economist. Instead, the Odinga political charisma seemed to have followed Raila, a glad-hander whose sophisticated political charm earned him a powerful following after his debut in elective politics in 1992.

Although Oburu was politically eclipsed by his younger brother, in whose political shadow he basked since 1994, when he returned to elective politics after inheriting his father’s Bondo seat, he remained an influential figure behind most of Raila’s monumental political decisions. According to sources, Raila could not take a decisive political step before consulting him.

With the death of his brother, Oburu finds himself thrust at the centre of the intricate and fragile network of political relationships between ODM and the government, and competing interests within ODM itself. Just as the diplomat had predicted in 1964, Oburu is currently in a position of influence, but his success will depend on how he navigates this complex situation and his grip on the politics of Luo Nyanza.

Follow our WhatsApp channel for breaking news updates and more stories like this.

The writer is a London-based Kenyan journalist and researcher