Premium

Jee Huu Ni Uungwana? Leonard Mambo Mbotela’s inaccuracies that beggar belief

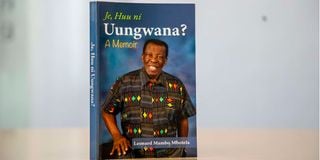

Leonard Mambo Mbotela’s book, ‘Je, Huu Ni Uungwana.’

I refer to the first instalment of the serialisation of Leonard Mambo Mbotela’s autobiography, Jee Huu Ni Uungwana? (Daily Nation, Dec. 21, 2023).

The second article, “I trace my roots to the Yao in Malawi” on page 7 is strewn with inaccuracies that beggar belief (The Nation.Africa version is headlined “Leonard Mbotela: Why I was named Mambo”).

He writes that his great-grandfather, Mbotela Senior, was captured in his home village in Malawi by slave traders and “put on a ship en route to Europe”.

The slave ship was never “en route to Europe” but sailing northwards towards the slave market in Zanzibar – reason for the treaty with the Sultan of Zanzibar to end slave trade, which Mbotela mentions! That was the destination for all captives including those from Kavirondo and Buganda (via Kenya) and from Luba in eastern DRC (via Tanzania) before the onward journey to the Middle East and India, not “Europe”, nor “America”.

Zanzibar was also a huge exporter of cloves and its plantations made use of large-scale slave labour.

He also says Freretown, in Mombasa, “was a major market for slaves.” It was a settlement on land acquired by the Church Missionary Society (CMS) for freed slaves.

Further, he says: “Whenever slaves from Kenya and parts of Tanzania were brought to this notorious market for sale, a huge bell was rang for the buyers to ‘select the goods’” .... “The huge bell that was rang in Freretown (as far back as 1800) for merchants to pick slaves is still there”.

Actually, sounding the bell warned when Arab slave ships were seen approaching Mombasa. This was in addition to its main function of calling people to service; it was a church bell! ACK Emmanuel Church in Freretown (Kengeleni) was built by the freed captives and is in use to this day.

He also says that Bartle Frere, who founded Freretown, spoke against slavery and “pushed for its abolition”.

More accurately, while Governor of Bombay in British India, he was sent by the Foreign Office to oversee the ban on the Indian Ocean slave trade. Settlements for freed captives later followed in Freretown and Kisulutini in Mombasa and Rabai respectively, this in tandem with the British Navy’s interception of slave ships at sea. The initiative (or “push”) to end the institution goes back further.

Mbotela further writes to say when the trade was abolished, the majority of the rescued slaves (in Freretown) were allowed to call the place home.

“Most of these rescued slaves from other countries were assimilated in the Kenyan coast and became part of the Swahili and Arab people.” Intermarriage has happened over time but they never “assimilated” in that their identity disappeared; instead they have always maintained a fairly large community while fully embracing their adopted Kenyan identity.

With respect, the irregularities in Mbotela’s story grossly contradict known facts.

— Martin Kimani, Engineering Technician

- The Public Editor is an independent news ombudsman who handles readers’ complaints on editorial matters including accuracy and journalistic standards. Email: [email protected]. Call or text 0721989264