Supreme Court judges (from left) Isaac Lenaola, Dr Smokin Wanjala, Philomena Mwilu, Chief Justice Martha Koome, Mohamed Ibrahim, Njoki Ndung'u and William Ouko.

As the Supreme Court of Kenya marks its 13th anniversary, attention is shifting to its record, its looming vacancies, and its growing influence in shaping the country’s political, social, and legal landscape.

Since its inception in 2011, the court has handled 734 cases, including 349 appeals, 17 election petitions, 28 advisory opinions, and 340 applications, according to Judiciary statistics. Over the course of 13 years, 13 judges have served on the apex court, including six who have since retired.

Chief Justice Martha Koome (left), Deputy Chief Justice Philomena Mwilu (top), Justices Isaac Lenaola and Ibrahim Mohamed. (Bottom row) Justices Smokin Wanjala, Njoki Ndung'u and William Ouko.

The current bench is led by Chief Justice Martha Koome and comprises Deputy Chief Justice Philomena Mwilu, and Justices Mohammed Ibrahim, Smokin Wanjala, Njoki Ndung’u, Isaac Lenaola, and William Ouko. Former judges include retired Chief Justices Willy Mutunga (2011–2016) and David Maraga (2016–2021), as well as Nancy Baraza, Kalpana Rawal, Phillip Tunoi, and Jackton Ojwang’.

Vacancies are expected in the near future. Justice Ibrahim is due to retire this year upon turning 70, while Deputy Chief Justice Mwilu will exit in 2027 or 2028, depending on her retirement choice. The court’s influence has been felt most in electoral law.

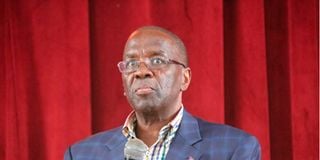

Former Chief Justice Willy Mutunga addresses students at Kenya Methodist University during a public lecture inside the institution's chapel on January 29, 2020.

Under Chief Justice Mutunga, it ruled that votes must be tallied and results declared immediately after polling closes, with jurisdiction over disputes shifting from the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) to the courts.

CJ Maraga’s tenure is remembered for the landmark nullification of the 2017 presidential election—the first in Africa—supported by Justices Mwilu, Lenaola, and Wanjala, while Justices Ndung’u and Ojwang’ dissented.

Sexual orientation

More recently, under CJ Koome, the court in 2023 upheld the right of LGBTQ groups to register associations, ruling that denial of registration based on sexual orientation was an unjustified violation of freedom of association under Article 36 of the Constitution. Justices Ibrahim and Ouko dissented.

In the 2022 presidential election petition, the court clarified that the IEBC acts collectively in tallying and verifying results, but that the formal declaration of a presidential election rests exclusively with the chairperson.

Beyond politics, the court has issued rulings with sweeping impact on governance, land, criminal law, family law, commercial law, and human rights. One of the most significant criminal law decisions came in 2017, when the court declared the mandatory death sentence for murder unconstitutional. It ruled that trial courts must exercise discretion and consider mitigating circumstances.

Similarly, in 2024, the court addressed mandatory sentences under the Sexual Offences Act, stressing that sentencing frameworks are set by Parliament, not judges. In land law, the 2023 Dina Management Limited case redefined ownership principles. The court ruled that a title deed alone is not conclusive proof of ownership if the root of the title is questionable. A bona fide purchaser must prove validity of title, due diligence, and consideration paid.

Senior Counsel Paul Muite.

The ruling drew criticism from Senior Counsel Paul Muite, who argued the court ignored the role of Lands Office staff in facilitating fraudulent titles. On human rights, the 2021 Mitu-Bell Welfare Society case barred forced evictions of squatters, affirming that long-term occupation creates a protectable right to housing, even if not a title. The court stressed that the government must safeguard the dignity of citizens in informal settlements. Family law jurisprudence has also evolved. The court held that spouses in marriage are entitled to a fair, not automatic, equal share of matrimonial property based on proven contributions. It also ruled that long cohabitation does not amount to marriage unless both parties intended it.

In commercial law, the Supreme Court in 2024 upheld Section 44 of the Banking Act, affirming that banks cannot raise interest rates or charges without prior approval of the Finance Cabinet Secretary.

In employment law, the court in 2023 ruled that the National Police Service could not unilaterally alter graduate constables’ benefits without mandatory advice from the Salaries and Remuneration Commission. The case stemmed from a long-standing policy, dating back to 1969, that offered graduate constables higher pay.

Death penalties

Kenya’s Supreme Court has also earned recognition beyond national borders. Courts in South Africa, Malawi, Uganda, Zambia, Ghana, Tanzania, Namibia, Seychelles, and the Caribbean Court of Justice have all cited its rulings.

The African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights referenced its 2017 decision declaring mandatory death penalties unconstitutional. South Africa’s Constitutional Court also borrowed its reasoning on matters of general public importance. This global footprint is partly attributed to technology, which has made judgments more accessible and encouraged cross-jurisdictional borrowing of legal principles.

The Supreme Court sits three times a year: from January to mid-April, from late April to July, and from mid-September to December. The Chief Justice, as President of the Court, allocates cases and determines sittings, assisted by the Deputy Chief Justice.

The remaining judges take precedence based on the order in which they took their oaths. The court also runs outreach programmes, particularly targeting universities.

Supreme Court Judge Lady Justice Njoki Ndung'u.

In July 2024, Justice Njoki Ndung’u delivered a lecture at Moi University’s School of Law on the court’s evolving criminal jurisprudence. She emphasised the need for dialogue between the judiciary and scholars, noting: “It is very difficult for Supreme Court judges to engage the public other than through their judgments, and we felt academia was the best way to share what we have been doing.”

While celebrated for bold rulings, the Supreme Court has also faced criticism. Its decisions on land titles, for instance, have sparked public disquiet. Critics argue the court has sometimes overlooked systemic government failures, such as fraudulent practices at the Lands Office.

Yet its jurisprudence has undeniably shaped Kenya’s constitutional democracy. From affirming electoral integrity to expanding housing rights, clarifying sentencing laws, and guiding economic regulation, the court has entrenched itself as a central player in Kenya’s governance.

Read also: