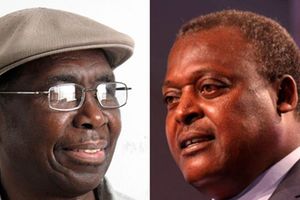

Marsden Madoka during a Nairobi business associates luncheon at the Villa Rosa Kempinski on September 15, 2016.

“... (Mzee Jomo) Kenyatta had a commanding tone. I froze... As Aide-de-Camp (ADC), I would... be on standby, waiting for the President to arrive from his Gatundu home in Kiambu.

During his presidency, Mzee Jomo Kenyatta never slept at State House, Nairobi. He constantly commuted to and from his rural home... If bored, he (Mzee) buzzed me and said, ‘ADC, nataka kwenda nyumbani (Marsden, I want to go home).’”

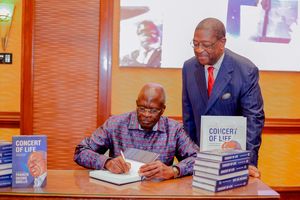

These are words from the memoir entitled At the Ready, by Major (Retired) Marsden Madoka, launched by President William Ruto on October 6, 2025, at State House, Nairobi.

Madoka’s descriptions of life as Mzee Jomo Kenyatta’s ADC express a sense of innocent wonder; they are colourful and sometimes hilarious.

The memoir reminds one of Cuban-born Italian novelist Italo Calvino’s 1972 novel Invisible Cities, in which a character asks Marco Polo, “Does your journey take place only in the past?”

Marsden Madoka during a Nairobi business associates luncheon at the Villa Rosa Kempinski on September 15, 2016.

In response, Polo says that what he described “was always something lying ahead, and even if it was a matter of the past, it was a past that changed gradually as he advanced on his journey, because the traveller’s past changes according to the route he has followed: not the immediate past, that is, to which each day that goes by adds a day, but the more remote past. Arriving at each new city, the traveller finds again a past of his that he did not know he had: the foreignness of what you no longer are or no longer possess lies in wait for you in foreign, unpossessed places.”

And this seems to be the case with Madoka. In his memoir, the journey takes place in the past, and that past changed as he took his own path, living his own life.

If State House was the dreamed-of place that contained Madoka as a young man who was Mzee Jomo’s ADC, he returned during the book launch as an old man, a little careworn but wise, with graver meditations and a humbler consciousness of the frivolity of it all.

Has State House changed, or, perhaps, has he? Maybe he remembered the first day at State House: how he stood at rigid attention, his first swift salute to the President, the hem of his new uniform itching at the wrists, the hush of State House in the off-hours, the sweet scent of polished wood and the muted panic of being around the president.

Maybe he remembered his former boss, Mzee Jomo Kenyatta — his presence like an urgent alarm turning to a hollow ringing, a monotone that felt far away and long ago — memories half-faded but never truly erased.

Born in 1943, Madoka’s life journey began in the Taita Hills. He writes, “I was born... to Reverend Allan Madoka and Dorothy Zighe...”

During the book launch, as he spoke, the feathered way he pronounced the sound “s” was assertive but distinct, carrying the signature Taita accent. And I wondered if every time he described something, he was saying something about Taita.

This seems like a season of memoirs in Kenya. Madoka’s descriptions of Mzee Jomo Kenyatta, especially his preference for spending the night at his Ichaweri home instead of State House, mirror those in Jason Njenga’s memoir (released two weeks ago) entitled Out of a Storm: Echoes of Freedom.

In the book, Njenga describes the mystery of Jomo Kenyatta: “wearing his famous brown leather jacket and a beaded Moslem cap (Taqiyah)... Charisma and culture mystically fused to give Mzee a rare spectacle as he waved his white flywhisk...”

Agreeing with Madoka on Mzee Jomo’s Ichaweri home, Njenga writes, “Mzee Jomo Kenyatta... used to commute from his home in Ichaweri, Gatundu, to State House, Nairobi, in the morning and back to his rural home in the evening.

It was rumoured that Mzee Kenyatta had tried to stay at State House after becoming President but could not sleep because he kept dreaming and seeing the last British Governor in Kenya, Malcolm MacDonald, tiptoeing into his bedroom at night or strolling in the daytime in his famed rose garden, plucking his beautiful and cherished flowers of red, white, purple, and pink roses—to Mzee’s annoyance.”

It is encouraging that both Madoka and Njenga have joined a growing list of Kenyans who have published their memoirs.

Memoirs have several benefits. The first benefit is cultural and historical preservation. Memoirs reclaim Kenyan history from colonial distortion. We get to tell our own stories instead of letting others define us.

While doing this, memoirs also preserve indigenous knowledge and oral traditions like the use of proverbs, rituals, and other wisdom that might otherwise be lost.

The second benefit is that memoirs give us a platform for emotional and generational healing. Writing about traumatic personal and national events is therapeutic and bridges generational gaps, as younger Kenyans understand the struggles and triumphs of elders, fostering empathy.

The third benefit is educational and literary value. Memoirs enrich curricula, and it’s encouraging that the Kenya Institute of Curriculum Development (KICD) is now approving the reading of memoirs in our schools.

As it has been said by Pindar, a lyric poet, “Unsung, the noblest deed will die.” Memoir is the song that saves noble deeds from oblivion. May we write our stories.

The writer supports people in writing their memoirs and other books.